The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

EUROPEAN EXPLORATION.

First Spain and then France considered the area now known as Oklahoma to be a likely spot for economic expansion in the New World. Native peoples who already lived there were seen both as a barrier to conquest and as a resource to exploit for economic and religious purposes. Oklahoma lay on the northern fringe of Spanish exploration of North America, which took place in the 1500s and 1600s, and on the western fringe of French exploration, which took place in the 1600s and 1700s. In effect, Oklahoma was a border region between those two empires in North America, and it served as a transportation corridor for their rival military and economic ventures. The value of studying their explorations of unknown territory lies in the descriptions that the explorers provided about the area's flora and fauna and its inhabitants and their cultures.

Oklahoma's original Native world included a number of tribal cultures that had used the area for economic subsistence for millennia before the Europeans' arrival. When first encountered by Europeans, the Caddo and the numerous Wichita subgroups were farmers living in established villages, mostly in the southern and eastern parts of the present state. The Plains Apache, Osage, Pawnee, and other nomadic groups found Oklahoma's northern and western prairie-plains regions to be a trove of animal and vegetable resources useful for subsistence. Over time, the composition of Native populations changed in the region, and the Comanche began moving into the area around 1700. Native peoples, however, were at first little troubled by the arrival of Christopher Columbus's ships off the coast of Central America in 1492.

Columbus, an Italian explorer working for the Spanish crown, originally sought a short water route to China that would give Spain an advantage in the spice trade. The Western Hemisphere provided an enormous physical barrier, and in seeking passage through it, Europeans thoroughly explored it over the ensuing two and one-half centuries. The Spanish might have given up, but the vast wealth discovered among the Inca and Aztec empires whetted their appetite for more gold and silver and stimulated them to explore further in "New Spain."

Columbus's arrival in the Europeans' "New World" has been viewed from a variety of perspectives by those who write history books. From the Native viewpoint, Columbus started an invasion of North and South America. In this view, the first Europeans are seen as despoilers of a natural environment in which people, animals, and plants lived in something of a balance or symbiosis, if not always in real or perfect harmony. From the viewpoint of the "conquerors," that is, the Spanish and French explorers, their chroniclers, and the many American historians who have since then studied their adventures, the Columbian discovery of the New World began an era of unprecedented economic opportunity for European kings and queens. They used the wealth of a new-found continent to finance their ambitions for political and economic control, building empires in Europe and elsewhere while spreading "civilization" to those who purportedly did not have it.

The Columbian exchange, comprising what the Europeans obtained from the American Indians and what the Indians obtained from the Europeans, became a hot topic for historians in the last decades of the twentieth century. Europeans obtained mineral wealth, new foods (including corn, beans, squash, potatoes, tomatoes, tobacco, and chile peppers), Christian converts, slaves, and other products. After observing the Native inhabitants, the newcomers also began to be interested in new ideas, such as "natural law." The Indians took advantage of opportunities presented by the Europeans and incorporated ideas and material objects into their cultures. They quickly adopted the use of the horse, eventually the use of iron and steel, weapons including the gun, and various manufactured goods, as well as tea, coffee, and sugar. On the other hand, American Indians were introduced to epidemic infectious diseases such as smallpox, malaria, yellow fever, measles, cholera, typhoid, and bubonic plague. A new religion, Christianity, was gradually forced upon them. In turn, they developed strategies for resisting enforced cultural change. And so the course of human history in the Western Hemisphere was altered permanently by the arrival of the Europeans, by their international political and economic rivalries, and by their persistence in expanding their influence throughout North and South America, even into the early nineteenth century.

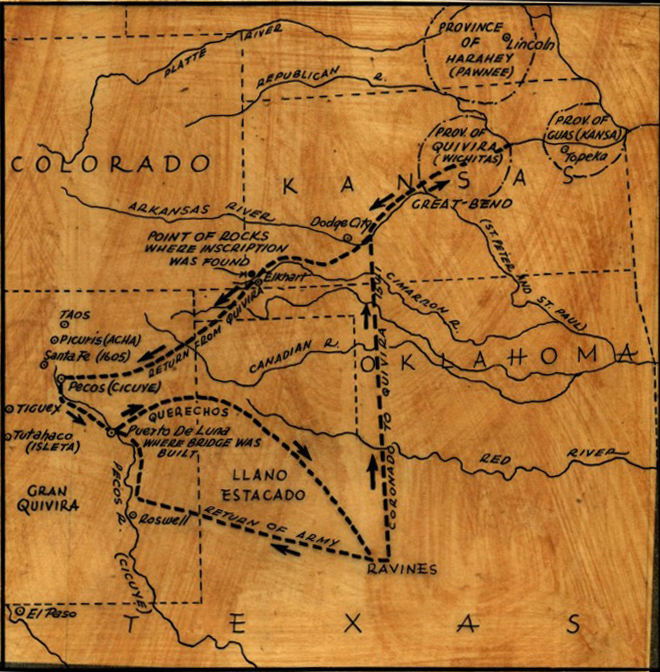

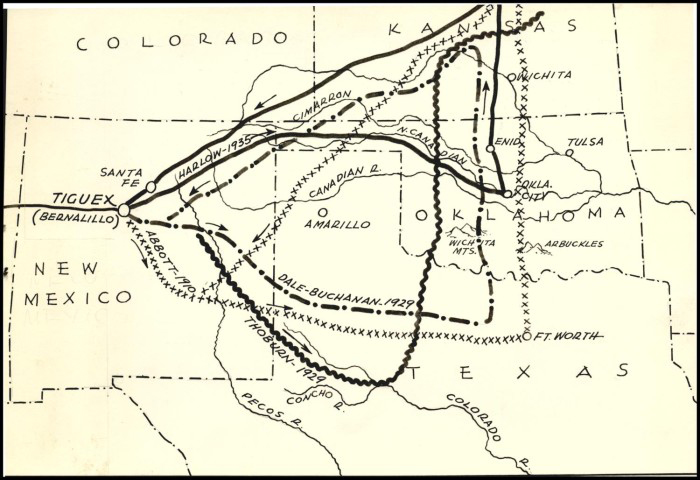

It took a generation or more for European explorers to visit the interior of North America for the first time. When they came, they were looking for gold and, as had become their custom, for Native peoples to convert to Christianity. Spaniards came northward out of Mexico to investigate New Mexico in the mid-1500s. Their efforts were prompted by rumors of seven golden cities, called "Cíbola," which Friar Marcos de Niza said he had discovered there in 1539. These towns, with buildings said to be made of gold, quickly assumed an important status in the Spanish ethos. Francisco Vásquez de Coronado left Mexico in 1540 to look for Cíbola in the northern region. From New Mexico in April 1541 his troupe went eastward, looking for a wealthy place called "Gran Quivira," and they crossed through the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles before arriving in late July in Kansas at a Wichita village presumed to be their destination. They found no gold. Ending his trip in disappointment, Coronado returned to New Mexico and then to Mexico in 1542.

Andrés do Campo, a Portuguese soldier, and several Franciscans, including Friar Juan de Padilla, had been with the Coronado expedition on its journey from New Mexico to Kansas and back. Interested in establishing a mission to convert the Wichita people, they returned to Quivira, probably in spring 1542. In 1544 they were attacked by a party of Kaw (Kansas) Indians, who killed Padilla and held do Campo and two others captive for a year. After escaping, the prisoners fled due south across the center of Oklahoma, approximately paralleling Interstate 35, and across Texas to Mexico. Legend tells that the men commemorated Padilla's death by taking turns dragging an enormous wooden cross during the entire length of their journey. Do Campo's description of the more direct route from Mexico to "Quivira" commanded some notice among Spanish officials, who later considered, but decided against, another expedition along the more direct route to search for the golden cities.

Another Spanish expedition penetrated the interior from the east. In 1539 Hernando de Soto began an exploration designed to find gold and converts in "Florida." The men traveled further and further westward and reached west-central Arkansas before turning back. Soto died of a fever in May 1542. Early histories of Oklahoma credit his men with crossing into and exploring far eastern Oklahoma. Best evidence, based on geographical description, indicates that scouting parties from the Soto expedition might have come into far eastern Oklahoma via the Arkansas River. Research in 1939 by the United States De Soto Commission clearly indicated that Soto died in Arkansas. However, in the 1990s, using archaeological data, historians discovered that Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, who succeeded Soto in command, led the party out of Arkansas and probably across the southeastern corner of Oklahoma along a well-known Indian trail that crossed the Red River into Texas.

A generation later, others became interested in the Quivira story. A small party led by Francisco Leyva de Bonilla and his lieutenant, Antonio Gutiérrez de Humaña, left Mexico for the north, wintered among the Pueblos in 1591, and, without permission from the Spanish government, headed east in search of Quivira. They perhaps traveled across the present Oklahoma Panhandle in 1592–93 on their way north to Wichita settlements in Kansas, where they both died. In 1598 Juan de Oñate established a colony in north-central New Mexico, the first successful European colony west of the Mississippi River. One purpose of settling so far north of Mexico was to provide a base of operations from which to seek the fabled wealth that had eluded Coronado. Governor Oñate decided to seek Quivira in 1601. Although historians dispute his actual path, it seems that he led a troop eastward, followed the main Canadian River across the Texas Panhandle, and then turned north at the Antelope Hills and traveled through present Ellis and Harper and perhaps Woodward and Woods counties of Oklahoma. As had Coronado, Oñate found nothing remarkable at a large Wichita village in Kansas, and he soon returned to his new colony. Oñate described the interior region and its inhabitants, primarily the Plains Apache and Wichita peoples, and noted the serious hostilities to be encountered by Europeans who ventured there. An excursion eastward from New Mexico in 1634 by Capt. Alonzo Baca is said to have traveled "three hundred leagues" (by Spanish measurement, about 750 miles) eastward to a large river that may have been the Arkansas (or by a stretch of the imagination, the Mississippi). During all of these ventures, notes were made, reports were submitted to the proper authorities, and a considerable store of knowledge was accumulated about the land and people of the Great Plains during the early period of exploration.

More importantly for Spain, the activities of these intrepid explorers over a fifty-year period made it possible for that nation to lay tentative claim to the region, despite the fact that ownership seemed to offer little in the way of economic compensation. The vast area that contained present Oklahoma technically remained French Louisiana from 1682 to 1763. The "border" between the two New World empires was unsurveyed and vaguely defined. Mythical Quivira notwithstanding, the Spanish crown lost interest in expanding to the northeast of New Mexico, viewing the region only as a buffer zone to be defended against the possible incursions of the French into New Spain's interior provinces of New Mexico and Texas.

The French entered the trans-Mississippi region after the voyage of René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, down the Mississippi River in 1682. Claiming much of the vast territory for France, La Salle envisioned a New World empire based on the fur trade with Indian tribes as partners. In 1686 Henri de Tonti established Arkansas Post, near present Gillette in southeastern Arkansas, and by the first decade of the 1700s traders had built a network with tribes west of the Mississippi. Establishing themselves in Illinois and at Mobile, New Orleans, and Arkansas Post, French explorers traveled further into the interior of North America, opening relations with various tribes and also seeking a route to New Mexico to open trade with its Spanish inhabitants. This perceived threat to New Spain's northern region led Spanish officials to encourage Native peoples in the borderland region, especially the Apaches, to aggressively oppose pro-French tribes.

Undeterred by potential human barriers, after establishing a trading center at Nachitoches in northwestern Louisiana in 1713–14, French voyageurs began to explore the environs of the Arkansas, Canadian, and Red Rivers, and their travels brought them into present Oklahoma. In 1718 Jean Baptiste Bénard, Sieur de La Harpe, a cavalry officer and merchant, received a concession from the French government for land in Louisiana, on the "upper waters" around the great bend of the Red River. His mission included establishing trade with the local tribes, and he sited a trading post, le Poste des Cadodaquious, or Kadohadacho Post, on a branch of the Red River in present in Bowie County, Texas. In 1719 he led a trading party into present Oklahoma. As with other explorers, his route has been variously described, but recent scholarship, based on narrative and archaeological evidence, indicates that he traveled through southeastern Oklahoma to the Canadian River, reached it near Eufaula, and then pushed northward. Narrative evidence and recent archaeological investigations indicate that the La Harpe party stopped in present Tulsa County, near Tulsa, just south of the Arkansas River (at the Lasley-Vore archaeological site). There they encountered a large village of the Tawakoni, a subgroup of the Wichita, and their chiefs, who agreed to become trading partners in return for guns. Earlier, La Harpe had sent Gaston Sieur du Rivage, the expedition's geographer, to explore the Red River, and that party traveled approximately 180 miles westward, upstream. They met with Kichai and Wichita, providing those peoples with their first European encounter, and learned valuable information about the Lipan Apache. In that same year of 1719, Capt. Claude-Charles du Tisné, a French Canadian and a military officer, visited the Osage in Illinois and moved southward in the autumn, probably entering present Oklahoma from the north along the Verdigris River. He reached a Wichita village that may have been near present Chelsea, in Rogers County, where he made a trade pact with the Wichita who were living there.

The French fur-trading presence in the southern trans-Mississippi region was fairly secure from that time forward. During the eighteenth century France and Spain vied for control of the Indians of Louisiana, Arkansas, eastern Texas, eastern Oklahoma, and Kansas. Louis Juchereau de St. Denis, founder of the French outpost at Natchitoches and its commander from 1719 through 1743, helped maintain French control of the fur trade, despite hostility from the Spanish (his former employers) in the Province of Texas. In fact, Spanish governors of Mexico fortified and settled in the Province of Texas in the early 1700s in part as a buffer against French incursion. During the last two decades of France's dominion over present Oklahoma the two nations were locked in competition in the New World and in the Old. From the early 1700s French traders, or coureurs de bois, kept up a lucrative trade relationship with the Wichita, Osage, Pawnee, and other tribes, and these activities influenced events in the French-Spanish borderlands, which included Oklahoma. The Spanish sent out a number of expeditions northeast from New Mexico to investigate French activities, which were reported occurring as far west as the country of the Utes, in Colorado.

As France endeavored to enlarge its trade territory, various exploring parties searched for a viable east-west route between Santa Fe and New Orleans, across present Oklahoma. The brothers Pierre and Paul Mallet, who were French Canadians, in 1740 followed the Canadian River and Arkansas River eastward to and southward from New Mexico to New Orleans. They may have been the first to travel entirely across present Oklahoma from east to west. Later, with André Fabry de la Bruyère, they reversed their course and traveled westward across the same area, and in 1750 they followed the course of the Red and Canadian rivers into the region again. Unfortunately, France made no real gain, either in trade or in knowledge, from their three ventures.

The French established a good relationship with the inhabitants of the Twin Villages, two Native settlements on opposite sides of the Red River. Located in present Jefferson County, Oklahoma, and Montague County, Texas, these two towns, well built and fortified with pallisaded walls, served as a trading center for the French, the Comanche, and a branch of the Wichita known as the Taovaya. The Texas-side village is also called Spanish Fort. One aspect of this economic nexus of European and Native tradesmen in the borderlands was a brisk exchange in which the Comanche offered Spanish captives, horses, and hides from New Mexico and Texas and Apache captives from the Plains. The French offered useful manufactured items, including guns and cloth. Their hosts, the Wichita, had the pick of all of these goods. In March–April 1758 the Comanche and various Wichita bands had attacked and destroyed Santa Cruz de San Sabá mission, a Catholic outpost ministering to the Lipan Apaches in the Province of Texas. This situation so aggravated the Spanish authorities that they sent Col. Diego Ortiz Parrilla, commander of the presidio near the mission, on a military expedition northward to attack the Twin Villages. In the autumn of 1759 the Wichita easily withstood the onslaughts of Ortiz Parrilla's soldiers, and the battle ended with the Spaniards' retreat.

The Franco-Spanish rivalry in the New World was about to come to an end. In 1763, after the end of a major European war, France transferred Louisiana to Spain. Little really changed in the interior, which had generally suffered benign neglect by the governments of both nations. In the 1770s Spanish authorities sent Athanase de Mézières y Clugny, commander of the military and trading post at Natchitoches, into the Red River region to visit various Wichita bands, and in 1771 he concluded a treaty with the Wichita proper, who, with their Comanche allies, had been harassing the Texas settlements. In 1778 he visited the Twin Villages and tried to induce Comanche leaders to come there for a conference, to no avail. Most of the Spanish efforts in the borderlands along the Red River, then, were aimed at keeping the Wichita bands and the Comanche from attacking the Texas settlements.

That also was the duty of Pierre, or Pedro, Vial, who in 1784 was commissioned by the Texas governor to travel along the Red River to find and talk with the Comanche. He subsequently conducted a series of expeditions to open a route to Santa Fe, none of which passed through Oklahoma. However, in 1792 he journeyed across country from Santa Fe to St. Louis, following a path generally consistent with the route of the Cimarron Cutoff of the Santa Fe Trail, which was opened in the 1820s across the Oklahoma Panhandle.

In 1800 French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte acquired Louisiana from Spain in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso. His aspiration for a great North American empire fell victim to his European ambitions and campaigns, however, and in 1803 he sold the entire region to the United States for $15 million. Thus, in the space of a century the vast trans-Mississippi region of Louisiana had three masters. However, the area of present Oklahoma had experienced no European settlement whatever, and, except for the arrival of the Comanche in the south plains, the presence of French coureurs de bois, and Native involvement in the fur trade, by 1800 the region remained much as it had been before the arrival of Columbus.

A significant legacy derived from the presence of the Spanish and French. Maps and descriptions accumulated over two hundred years, and these are still examined by scholars for information on a variety of topics ranging from environmental change to ethnic groupings to population movement. One of the most interesting legacies of the European rivalry for the interior has been the intense interest it continues to provoke among historians and archaeologists concerning "the exact route" of each expedition. This has served those who love "history by the inch" and has also served a variety of public relations purposes, with towns in New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, Arkansas, as well as in the American South, making claims of their area having been explored by Spanish conquistadors or French voyageurs.

Coronado's route, for instance, has been vigorously disputed by historians for nearly a century. Towns in Central Texas and as far north as Nebraska claim that Coronado slept there. Liberal and Lyons, Kansas, have Coronado museums. In 1942 the federal government organized a Coronado Cuarto-Centennial celebration, with activities in communities all along the supposed routes. Oklahoma's Coronado Commission members included John Frank Martin (chair, Oklahoma City), Fred Coogan (Sayre), Everett Murphy (Kingfisher), Earl Gilson (Guymon), Fowler Barden (Mangum), and Emmit Talley (Mangum). A black granite marker two miles east of Forgan, in Beaver County, commemorates Coronado's passage. In 1992 another federal commission studied the Coronado route and concluded that it was impossible to establish it with any certainty.

Similarly, Soto's route remains in dispute, with some question as to whether the expedition ever entered Oklahoma. Federal De Soto Commissions in 1939 and 1987 conducted investigations. Much effort has also been expended to find the exact meeting spot of La Harpe and the Wichitas who became French allies in 1719. Various researchers from the early 1920s through 2002, historians and archaeologists alike, have investigated the narratives and the archaeology of proposed locations, and the site has been variously placed near Muskogee, near Leonard, and, most probably, near present Jenks, a suburb of Tulsa.

The French legacy is apparent in geographical designations such as Verdigris and Illinois rivers and Sans Bois and Ouachita mountains, town names such as Poteau and Vian, and in family names such as Chouteau. The Spanish legacy is less apparent but observed in geographic designations in the Oklahoma Panhandle, such as Cimarron and Canadian rivers and Corrumpa, Carrizo, and Trujillo creeks. These clearly indicate a Spanish and New Mexican presence. The explorers' primary legacy remains their extensive descriptions of Native peoples and their cultures. These insights, although distorted by the lens of European Christianity, still inform ethnohistorians and geographers today.

Bibliography

Herbert Eugene Bolton, Coronado, Knight of Pueblos and Plains (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1949).

Herbert Eugene Bolton, ed., Spanish Exploration in the Southwest, 1542–1706 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916).

James F. Brooks, Captives and Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002).

James E. Bruseth and Nancy A. Kenmotsu, "From Naguatex to the River Daycao: The Route of the Hernando de Soto Expedition through Texas," North American Archaeologist 14 (No. 3, 1993).

Alfred W. Crosby, The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1972).

David Ewing Duncan, Hernando de Soto: A Savage Quest in the Americas (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996).

Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint, eds., The Coronado Expedition to Tierra Nueva: The 1540–1542 Route Across the Southwest (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 1997).

Charles M. Hudson, Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando De Soto and the South's Ancient Chiefdoms (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997).

Anna Lewis, "Du Tisne's Expedition into Oklahoma, 1719," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 3 (December 1925).

Anna Lewis, "French Interests and Activities in Oklahoma," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 2 (September 1924).

Anna Lewis, "La Harpe's First Expedition in Oklahoma, 1718–1719," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 2 (December 1924).

Leslie A. McRill, "A Review of the De Soto Expedition in Territories of our Present Southern United States," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 39 (Spring 1961).

National Trail Study and Environmental Assessment, Coronado Expedition, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 1992).

George H. O'Dell, La Harpe's Post: A Tale of French-Wichita Contact on the Eastern Plains (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002).

Delbert F. Schafer, "French Explorers in Oklahoma," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 55 (Winter 1977–78).

A. B. Thomas, "The First Santa Fe Expedition, 1792–1793," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 9 (June 1931).

A. B. Thomas, "Spanish Exploration of Oklahoma, 1599–1792," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 6 (June 1928).

Russell Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987).

Ralph H. Vigil, Frances W. Kaye, and John R. Wunder, eds., Spain and the Plains: Myths and Realities of Spanish Exploration and Settlement on the Great Plains (Niwot: University Press of Colorado, 1994).

Robert S. Weddle, The French Thorn: Rival Explorers in the Spanish Sea, 1682–1762 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1991).

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Dianna Everett, “European Exploration,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=EU002.

Published January 15, 2010

Last updated

May 6, 2019

© Oklahoma Historical Society