The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

FLOYD, CHARLES ARTHUR (1904–1934).

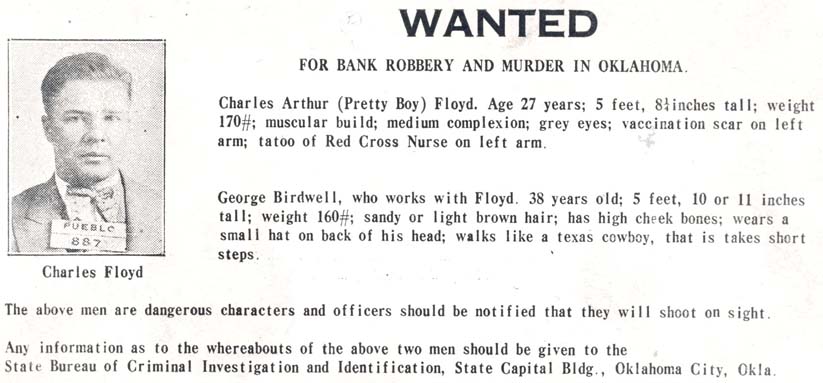

Known as "Choc" Floyd or "Pretty Boy," Oklahoma's most notorious and glorified folk bandit, Charles Arthur Floyd also became one of the nation's most celebrated criminals. He was immortalized in song by Woody Guthrie and by the fictional Joad family in John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath. This Robin Hood figure, beloved of America's dispossessed and downtrodden of the Great Depression, was also a wanton bank robber and a man known to J. Edgar Hoover and the law enforcement establishment as "Public Enemy Number One."

Born on February 3, 1904, near Adairsville in Bartow County, Georgia, Floyd was the second son and fourth of six surviving children of Walter Lee Floyd and Mamie Helena Echols Floyd. Descended from Georgia hill farmers, the Floyds traced their lineage through three centuries of Welsh settlers. Fleeing the hills of northwestern Georgia in 1911 in search of opportunities farther west, the Floyds, with young Charley in tow, joined family and friends in Sequoyah County, in eastern Oklahoma near the Arkansas border.

The spirited and popular Charley proved to be a bright boy with mischief on his mind. Raised on small tenant farms near Sallisaw and Akins, the youngster worked long, arduous hours with his family in fields of cotton and corn. He grew weary of the drudgery of farm life and found solace in the many tales of heroic figures and outlaws spawned in the region, especially Missouri bandit Jesse James. Charley also learned the art of making corn liquor, or moonshine. By his early teens, he had earned the nickname "Choc," after his fondness for Choctaw beer, a popular home brew made of barley, hops, tobacco, fishberries, and a small amount of alcohol.

At age sixteen, after a few minor scrapes with the law, Choc Floyd took to the road as a hired hand on the wheat-harvest circuit throughout Oklahoma and Kansas. Soon tiring of the hard work, he became involved in bootlegging operations and other illegal activities. In Wichita Floyd found a criminal mentor in John Callahan, a shadowy figure who operated one of the largest fencing operations in the Midwest. Floyd returned to his family and friends in Oklahoma, and in 1924 he married Ruby Hardgrave, the daughter of a tenant farmer. Later that year, Ruby gave birth to a son, Jack Dempsey Floyd, named after the world-champion boxer.

Devoted to his wife and son but still restless with life as a dirt farmer, Floyd traded five gallons of corn whiskey for a pearl-handled pistol. In 1925 he and a friend jumped a freight train headed east and left behind the Cookson Hills of Oklahoma. In St. Louis on September 11, 1925, he took part in a payroll robbery that netted $11,929 and earned him a five-year sentence in the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City.

On January 4, 1929, Ruby Floyd filed for divorce, charging her incarcerated husband with neglect. Floyd did not contest the action, and she took custody of their four-year-old son. Through the years Floyd continued to see his former wife and son and lived with them in both Fort Smith, Arkansas, and in Tulsa. In March 1929, following release from prison in Missouri, Floyd headed straight to Kansas City, ready to put to use the education in crime he had received from veteran convicts behind bars. During a card game at Mother Ash's boardinghouse in Kansas City, Floyd met his future girlfriend, Beulah Baird, who gave him the colorful moniker "Pretty Boy."

From almost immediately after leaving prison until his death in 1934, Floyd, usually accompanied by one or more accomplices, carried out a string of more than thirty successful bank robberies across the Midwest, primarily in Ohio and Oklahoma. Authorities also implicated him in several murders resulting from gun battles with law officers or rival criminals. It later became known that Floyd did not commit many of the crimes attributed to him. On April 9, 1932, Floyd shot and killed Erv Kelley, an Oklahoma lawman turned bounty hunter, during a foiled attempt to ambush Floyd near Bixby, Oklahoma. One of Floyd's most illustrious bank jobs occurred later that year in his hometown when he and his partner George Birdwell robbed the Sallisaw State Bank in broad daylight while friends and family watched.

Floyd's whirlwind bandit career began to unravel on June 17, 1933, when he and Adam Richetti became the chief suspects in the infamous Kansas City Massacre. This bloodbath at the Union Station resulted in the deaths of four law officers and allowed J. Edgar Hoover to further empower himself and the FBI. Although both Floyd and Richetti ultimately paid with their lives, it is now clear, based on new evidence, that neither was involved in the brutal slaughter. On October 22, 1934, local law officers and FBI agents led by Melvin Purvis shot and killed Floyd in a cornfield near East Liverpool, Ohio. Floyd's body was returned to the Oklahoma hills, and he was laid to rest on October 28, 1934, at Akins Cemetery. A crowd estimated at more than twenty thousand made it the largest funeral in Oklahoma history.

See Also

Bibliography

Roger A. Bruns, The Bandit Kings: From Jesse James to Pretty Boy Floyd (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1995).

Paul Kooistra, Criminals as Heroes: Structure, Power, Identity (Bowling Green, Ky.: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1989).

Robert Unger, The Union Station Massacre: The Original Sin of J. Edgar Hoover's FBI (Kansas City, Mo.: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 1997).

Michael Wallis, Pretty Boy: The Life and Times of Charles Arthur Floyd (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992).

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Michael Wallis, “Floyd, Charles Arthur,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=FL004.

Published January 15, 2010

Last updated

December 8, 2022

© Oklahoma Historical Society