The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

BANKING INDUSTRY.

As formal business institutions, banks emerged very slowly during nineteenth-century Indian Territory but quickly appeared with the land runs that populated central and western Oklahoma Territory. As occurred during the early settlement periods of other states, in Oklahoma local merchants often performed the role of banker during the Territorial Era. In the 1870s, for example, James J. McAlester in Indian Territory (I.T.) provided farmers, coal miners, and other residents banking services from his mercantile store. In Doaksville, Choctaw Nation, I.T., competition occurred between the Doak and Times Mercantile Company and the Berthelet, Heald, and Company, both of which performed banking functions. In 1873 James A. Patterson established the Patterson Mercantile Company in Muskogee, I.T., where he provided a safe for out-of-town customers, especially wealthy cattlemen who traveled with large amounts of currency in canvas bags. He eventually established a bank that offered passbook and checking accounts.

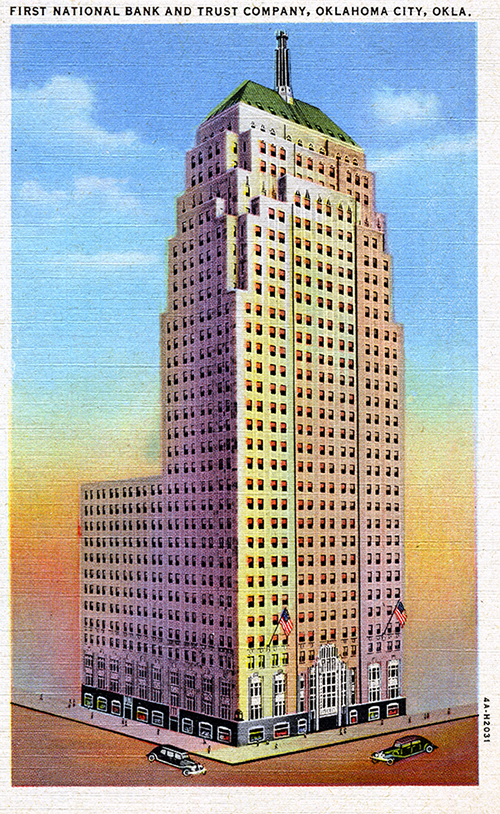

When Oklahoma Territory was first opened to non-Indian settlers in 1889, banks were some of the first businesses established. Within a few days of the land run on April 22, 1889, at least nine were opened. One of these, the Oklahoma Bank, was started by Thomas M. Richardson in a tent. Renamed First National Bank of Oklahoma City in 1890, the bank moved into a wooden building at the corner of Main and Broadway streets, establishing what remains the banking center of Oklahoma City. However, the state's oldest continuously operated banking institution is Stillwater National Bank and Trust Company, established in 1894.

Oklahoma's early banks were private businesses unhampered by the inconveniences of strict laws. Although the U.S. Congress applied the National Banking Act to Oklahoma Territory as well as Indian Territory in the Organic Act of 1890, only seven national banks opened. Virtually anyone who could attract deposits could start a bank. In 1893 the Oklahoma territorial legislature required that banks provide names of officers and list bank activities but did not require a minimum deposit requirement for operating. In 1897 a regulatory code was passed requiring all banks to be incorporated and to operate under the supervision of a bank commissioner.

The early 1890s were difficult for many businesses, especially banks. The panic of 1893 started in New York when the stock market crashed but quickly spread throughout the nation. Thomas Richardson was still in charge at First National Bank when the run on the banks began. Like most bankers, he realized the need to maintain confidence in the bank's ability to pay. When long lines of people demanded cash for their deposits, Richardson closed the doors after paying out for twelve hours. He promised that if anyone failed to have money returned the next day, that person could hang him from a nearby post. Of the four banks in Oklahoma City, his and the newly established State National Bank both finally failed to pay depositors and had to close. However, the two failed banks eventually paid out all deposits and merged in 1897.

After another nationwide bank run in 1907, the new state of Oklahoma became the first state in the nation to have compulsory deposit insurance. Funded by a 1 percent tax on banks, the Bank Guarantee System was used to pay depositors when a bank failed. The first failure came in 1908, and with it came the charge that the system was an excuse to close fundamentally sound banks for political reasons. Another problem with compulsory insurance surfaced with the 1909 failure of Oklahoma City's Columbia Bank and Trust Company, with $2.8 million in deposits. This bank, advertising guaranteed deposits, had grown rapidly. Bank officers had invested with little regard for the safety of these funds, a common problem associated with deposit insurance.

By 1907 the state had 883 banks. Most were very small establishments, and local pride required that the bankers reside in the community. The tradition of unit banking was established, and laws prohibited branch banking until the 1980s. In the future, chain banking, in which a holding company owned several banks, allowed some diversification.

Failures of rural banks in the 1920s preceded and contributed to the Great Depression. The Oklahoma economy depended on agriculture, mining, and oil. World War I stimulated these businesses. With the increase in prices, farms, mines, and oil drilling were expanded with borrowed money. In the early 1920s as prices fell, these loans were not repaid. Farm foreclosures reached 50 percent in Oklahoma between 1926 and 1930, the third highest ratio in the nation. Foreclosures provided little relief to the lenders however, and banks that depended on these loans failed. Faced with staggering claims, the state legislature abolished the bankrupt Bank Guarantee System in 1923.

World War II helped wean Oklahoma banks from their dependence on agricultural lending. First National Bank of Oklahoma City financed the acquisition of land for a U.S. Army Air Corps base and supply depot. Other city bankers pledged $294,000 to open Midwest Air Depot (later Tinker Air Force Base). Oklahoma businesses received $4.6 million in federal contracts during the war. Addition of a new Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) training center, expansion of oil drilling, and revival of the agricultural industry soon created a booming postwar economy. Consequently, Oklahoma City's population grew 32 percent, and Tulsa's rose 81.7 percent from 1950 to 1960. In addition, the post–World War II need for housing loans continued to grow through the 1950s.

Oklahoma bankers contributed to the growth in the economy by forming the Oklahoma Finance Authority in the 1950s. This organization attracted industry by putting up 25 percent of an industrial development project's costs. The local banks would then lend 50 percent of the cost, and the developer only had to front costs of 25 percent. Oklahoma bankers did not neglect agriculture, however. They opened new departments to serve farmers and ranchers. In the 1950s bankers contributed to 4-H and Future Farmers of America in order to make early connections to agriculture, which in spite of the declining numbers of farmers remained the most important business in the state.

The next big growth industry was oil. By 1960 National Bank of Tulsa was known as the "oil bank of America," and oil loans were instrumental in the rise of the First National Bank of Oklahoma as the largest bank in the state. From 1960 to 1969 forty-seven new banks opened. In the 1960s banks were often started with the goal of growing in new population centers (suburbs) and then being acquired by holding companies that owned older banks. Bankers tried to supplement the local deposits and attract out-of-state customers by promotions such as "free gifts," attractive lobby events, and higher interest on large deposits. The older banks launched a 1970s construction boom for downtown bank headquarter buildings, often replacing or supplementing the towers they had constructed in the 1950s. Liberty Bank started the trend in 1968, erecting the tallest structure in Oklahoma City.

In the early 1980s high interest rates hurt many industries. Farmers and ranchers, always saddled with debt and needing loans, caused the interest rate to increase in the late 1970s. As interest rates rose, agriculture suffered, "problem loans" multiplied, and the collateral (land, crops, or livestock) lost value. Banks tried to offset this trend by moving toward the fast-growing petroleum industry and lending money to oil speculators. A 1979 revolution in Iran had reduced world oil production and increased crude oil prices, stimulating deeper drilling and more wells. However, over production soon brought the oil prices tumbling down again. Oklahoma banks quickly developed trouble as loans defaulted. In 1982 the failure of one of these oil banks, the Penn Square Bank of Oklahoma City, caused lasting damage to the United States' banking system.

The Penn Square problem kept Oklahoma banks subdued for the remainder of the 1980s. Between 1982 and 1987 sixty-nine of the state's banks failed. When the Farmers and Merchants National, in Hennessey, Oklahoma, closed on December 5, 1985, it was the thirteenth Oklahoma bank and one of 119 banks nationally to fail that year. In 1985 Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska each had thirteen bank closings and ranked the highest in the nation for number of bank failures. Like other midwestern banks that suffered from uncollectible agricultural loans, many Oklahoma bank closures occurred in small, rural communities. In the 1990s the Gulf War temporarily increased defense spending and oil prices, which helped the banks. After the war ended, banks began to merge and be acquired by out-of-state banks. The number of banks dropped from 394 in 1992 to 286 in 2000.

In 2003 there were 273 banks and five savings banks in the state of Oklahoma. Although Oklahoma banks are relatively small, with total combined assets of $46 billion, Oklahoma bankers have maintained influence in the industry. In the early twenty-first century Altus banker C. Kendric Fergeson chaired the 2003–04 American Bankers Association (ABA). Oklahoma Commissioner of Banks Mick Thompson chaired the 2003 Conference of State Bank Supervisors, and Bristow banker Albert C. Kelly chaired the 2003 ABA's Community Bankers Council. In 2003 Stillwater National Bank continued to be one of the larger, but still typical, Oklahoma banks. It was owned by Southwest Bancorp, which had assets of $1.4 billion and, due to liberalized branching laws in the 1980s, had consulting and investing services in Oklahoma and in Texas.

Bibliography

"Banks and Banking," Vertical File, Oklahoma Room, Oklahoma Department of Libraries, Oklahoma City.

"Banks and Banking," Vertical File, Research Division, Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma City.

Lynne Pierson Doti and Larry Schweikart, Banking in the American West: From Gold Rush to Deregulation (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991).

E. H. Kelley Collection, Research Division, Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma City.

Loren C. Gatch, "'An' the west jes' smiled': Oklahoma Banking and the Panic of 1907, The Chronicles of Oklahoma 87 (Spring 2009).

Loren Gatch, "'This is Not United States Currency': Oklahoma's Emergency Scrip Issues during the Banking Crisis of 1933," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 82 (Summer 2004).

Michael Hightower, "Penn Square: The Shopping Center Bank that Shook the World, Part 2: Bust," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 90 (Summer 2012).

Norbert R. Mahnken, "No Oklahoman Lost a Penny: Oklahoma's State Bank Guarantee Law, 1907–1923," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 71 (Spring 1993).

James Smallwood, An Oklahoma Adventure: Of Banks and Bankers (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979).

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Lynne Pierson Doti, “Banking Industry,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=BA011.

Published January 15, 2010

© Oklahoma Historical Society