The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

CATTLE INDUSTRY.

From former cotton farms reseeded to tame grasses in the east to the native buffalo-grass sod on the High Plains of the Panhandle, more than five million cattle were to be found on the farms, feedlots, and ranches of Oklahoma at the beginning of the twenty-first century, making it the number four beef-producing state in the United States. From early in its history as Indian Territory, Oklahoma, thanks to its combination of nutritious grasses and productive grain farms, has been a major factor in the cattle industry.

The origins of Oklahoma cattle raising go back to the 1830s when the Five Tribes (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole) were removed from the southeastern United States and resettled in Indian Territory. In addition to bringing large herds of livestock with them, they also practiced a system of communal land ownership that favored open range grazing. This in turn led to increased herd sizes, because until the California gold rush of the 1850s there was no readily available market for their cattle. As demand grew, so did stock raising, so that by the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 the Cherokee Nation alone had nearly a quarter-million head of cattle. Unfortunately, the havoc of the war and the depredations of cattle thieves resulted in an estimated loss of three hundred thousand head among the Five Nations by 1865.

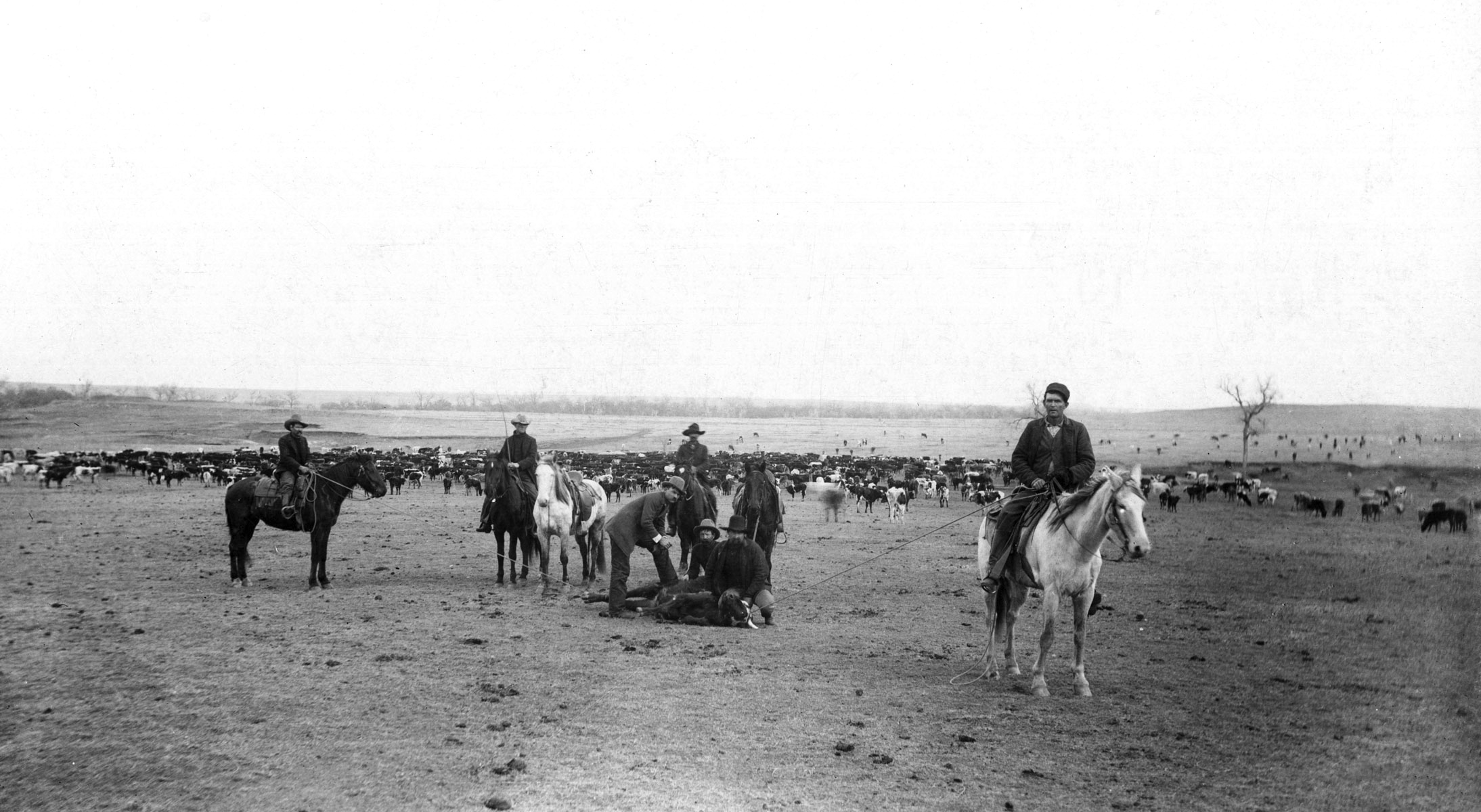

Immediately following the Civil War the era of the great cattle drives from Texas began. After an initial and discouraging attempt to deliver cattle to Sedalia, Missouri, in 1866, the northern migration of cattle began in earnest with the opening of the shipping center at Abilene, Kansas, in early September 1867. Oklahoma, lying between the vast cattle ranges of Texas and the colorful cow towns of Kansas and Nebraska, was crossed by the two major stock routes of the Old West, the Chisholm Trail and the Western Trail, thus contributing not only materially to the economic boom of the cattle drives but also mythically to the creation of America's greatest folk hero, the cowboy. Most of the cattle herds crossed Indian Territory at a leisurely pace, grazing on both public and Indian lands, sometimes paying a toll on the latter for grazing permits.

Cattle on both trails crossed and grazed on the Cherokee Outlet, a six-million-acre strip of good grass extending some 150 miles east to west and sixty miles north to south. It had been granted to the Cherokee as an outlet to the buffalo hunting regions on the plains. Toward the latter end of the trail-drive era (roughly 1866 to 1886), cattle raisers from both Texas and Kansas began negotiations with the Cherokee Nation to place cattle legally on the Outlet. Historian Edward Everett Dale has called the Cherokee Strip Live Stock Association, loosely organized in 1880 and more formally structured in 1883, the greatest livestock organization in the world during its ten-year existence. Despite the wishes of both cattlemen and Cherokee officials, the U.S. government ordered the removal of cattle in order to open the Outlet for white settlement, culminating in the great Cherokee Outlet Opening of 1893. As in the rest of the central plains, the range-cattle era in Indian Territory was brief. In 1895 the open range was declared closed by the territorial legislature, and by the first year of the new century almost all Indian lands had been settled.

Cattle raising in Oklahoma during the twentieth century, as in the rest of the plains, moved toward improved breeds and more scientific methods of handling. Trail drives gave way to railroads, then trucks, and finally stock trailers. One effect of barbed wire and windmills was that Oklahoma stockmen could keep scrub bulls away from their cows and thus upgrade their herds. In the first half of the twentieth century the Hereford was the preferred breed, but Aberdeen-Angus became dominant in the latter half. One prominent Hereford breeder was oilman and rancher Roy J. Turner, who served both as governor of Oklahoma and as president of the American Hereford Association. Other oilmen who became major stock raisers include William G. Skelly, Dean A. McGee, and Robert S. Kerr. Turner's annual production sales, along with those of ranches in "Hereford Heaven," as central Oklahoma was often termed, attracted buyers from throughout the West. Turner's most prized bull, Hazford Rupert 81st, was featured on the cover of Life magazine. The Oklahoma Hereford Tour, organized by Phil Lowery, J. A. Blaydes, and William L. Blizzard in 1928, was the nation's first. Another Oklahoma first was the development of the Brangus breed, a Brahman/Angus cross that was officially recognized by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1949.

Among the country's best-known ranches was the 110,000-acre 101 Ranch, founded in 1893 by Col. George W. Miller. The ranch was famous not only for being known as the largest diversified farm and ranch in America, but also for its internationally popular Wild West show (1905–31), organized by the Miller brothers, Joe, Zack, and George, Jr. Another among many historic Oklahoma ranches is the Hitch Ranch, begun when James K. Hitch drove a small herd of longhorns from southeast Kansas to the Panhandle in 1884 or 1885. The ranch, with headquarters at Guymon, has since expanded into Kansas and the Texas Panhandle. In 1953 Henry C. "Ladd" Hitch, Jr., opened one of the first feedlots in the Southwest, an enterprise that by the early twenty-first century had a feeding capacity of some 160,000 head of cattle.

One of the most storied cattle-raising regions of the state is the Osage Hills of Osage County, an area that, with the neighboring Flint Hills of Kansas, is renowned for its lush bluestem pastures. In the 1930s the 100,000-acre Chapman-Barnard Ranch was the largest in the state, with one pasture alone measuring some nineteen thousand acres. It was not unusual in the spring for as many as 250 railroad stockcars a week to unload Texas cattle for fattening on the Chapman-Barnard Ranch. At the turn of the twenty-first century part of the ranch forms the Nature Conservancy's Tallgrass Prairie Preserve.

In 1910 Edward Morris opened both a meat-packing plant and a stockyards in Oklahoma City. The packing plants are now closed, but whereas other major terminal markets such as Chicago, Kansas City, Omaha, and Wichita are defunct, the Oklahoma National Stockyards are thriving. Served by excellent highway facilities and centrally poised between the calf-producing farms and ranches to the east and the stocker-feeder, grain-producing area to the west, the Oklahoma City yards were the largest stocker-feeder cattle market in the country at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

See Also

BARBED WIRE, CATTLE DRIVES, RANCHING–AMERICAN INDIAN, TEXAS FEVER

Bibliography

Edward Everett Dale, "The Cherokee Strip Live Stock Association," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 5 (March 1927).

Norman Arthur Graebner, "History of Cattle Ranching in Eastern Oklahoma," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 21 (September 1943).

Gary Kraisinger and Margaret Kraisinger, The Western: The Greatest Texas Cattle Trail, 1874–1886 (Newton, Kans.: Mennonite Press, 2004).

Joseph G. McCoy, Historic Sketches of the Cattle Trade of the West and Southwest (1874; reprint, Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1940).

J'Nell L. Pate, America's Historic Stockyards: Livestock Hotels (Fort Worth, Tex.: TCU Press, 2005).

Laban Samuel Records, Cherokee Outlet Cowboy: Recollections of Laban S. Records, ed. Ellen Jayne Maris Wheeler (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995).

W. Edward Rolison, "Murder in Custer County: A Case Study and Legal Analysis of Herd Law versus Free Range in Oklahoma Territory," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 90 (Fall 2012).

William W. Savage, Jr., The Cherokee Strip Live Stock Association: Federal Regulation and the Cattleman's Last Frontier (1973; reprint, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990).

Jimmy M. Skaggs, ed., Ranch and Range in Oklahoma (Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Historical Society, 1978).

Roy P. Stewart, "Henry C. Hitch and His Times," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 50 (Spring 1972).

Donald E. Worcester, The Chisholm Trail: High Road of the Cattle Kingdom (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1980).

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Jim Hoy, “Cattle Industry,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=CA077.

Published January 15, 2010

Last updated

May 6, 2019

© Oklahoma Historical Society