The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

TRI-STATE LEAD AND ZINC DISTRICT.

Lead and zinc mining ranks high among Oklahoma's historically significant extractive industries. Lead and zinc, found together, occur in various locations, including the Arbuckle Mountains near Davis and Ravia, the Wichita Mountains near Lawton, the Ouachita Mountains of northeastern McCurtain County, and in Ottawa County. By far the most productive have been the vast deposits found in the 1,188-square-mile Tri-State District (also called the Joplin Region because financial, manufacturing, and transportation industries that served the district originally centered in Joplin, Missouri).

Lying along the southwestern flank of the Ozark Mountains, the district extends from southwestern Missouri across southeastern Kansas and encompasses Ottawa County, Oklahoma. There, lead ore, primarily galena (lead sulphide, PbS), and zinc ore, primarily sphalerite (zinc sulphide, ZnS, also called "jack," blende, or "resin jack"), occur in subsurface rock formations and are dug in shallow or deep mines. The Oklahoma mines tended to be deeper than others of the Tri-State. Concentrating mills separated crude ore into its constituent lead and zinc and chat or tailings to be discarded. The ores were then smelted and made ready for manufacturing. Lead was used for plumbing pipes, for linings in airtight containers, in paint, and as bullets and shot; zinc was used for galvanizing wire and sheet iron, for roofing and stove boards, and also in dyeing and fireworks.

Lead and zinc mining was the Tri-State District's principal economic activity for more than eighty years. Production commenced in Missouri circa 1850. Although some surface mining produced lead shot during the Civil War, the Oklahoma section remained commercially untapped until the Peoria Mining Land Company of New Jersey opened shafts around Peoria, Indian Territory (present Ottawa County) in 1891. Crude ore was at first hauled by wagon and later by truck to Missouri for milling. Other mining areas rapidly appeared, beginning with discoveries around Quapaw (1904) and continuing with Miami, Picher, and Commerce (1905–08). Landowners leased their property to hundreds of small "mining land and royalty" companies, which operated mines and mills. In the early decades, quite often the operator was actually the man who physically worked the mine, the mill, and the smelter. The largest ore strike came in 1913 in downtown Picher on the Crawfish allotment.

The "mineralized" area of Ottawa County was located on land historically belonging to the Quapaw tribe. Allotment of 240 acres to each individual Quapaw was followed by an 1897 ruling that allowed leasing of allotments for mining. This was followed by several lawsuits and resulted in approximately one-sixth of the Quapaw being able to collect lease payments and mineral royalties. By 1927, 248 mills operated in the field.

During the heyday of lead and zinc in Oklahoma, dozens of mining camps grew up, including Lincolnville, Hattonville (now Commerce), Picher, Century, and Cardin. These at first had the characteristics of other mining camps of the American West, including crime, violence, and overcrowded, unsanitary conditions. Existing towns such as Miami, Quapaw, and Peoria, with nearby camps, boomed as well.

Railroads boosted production in the Tri-State District. The northern area enjoyed rail service in the 1870s, and when the Ottawa County district developed, rail lines had been extended into that region. By 1900 the St. Louis and San Francisco, or Frisco, Railway controlled most of the lines. The Northeast Oklahoma Railroad (NEO) extended spurs from the main lines out to the mines and camps. By 1918 a network of electric railway lines, or interurbans, allowed miners to commute from towns to the mines. The entire Tri-State was interlaced with an intricate transportation system for people and ore.

Economic stability and steady population growth characterized the district and the Ottawa County mining towns until the Great Depression of the 1930s. In 1924, the peak employment year, 11,187 men, almost all American-born whites raised on farms within the district, made their living in the mines. Despite the job hazards—collapses, explosions, accidents, stale and dusty air, polluted water, and diseases—and comparatively low wages, Tri-State miners tended to remain employed, stay in the same town, make homes, and raise crops in their spare time. Generally, they did not even migrate to jobs outside the district during brief downturns in production. They did not favor labor unions and rarely conducted strikes, at least until the Depression. Thereafter, hard times took a toll, and unions began successfully to recruit, with strikes and violence resulting. By 1953 only one-quarter of the district's four thousand workers were unionized.

Between 1915 and 1930 leasing and royalty companies began to buy, rather than lease, mining land, and consolidated into a few dozen large operating companies. After the peak year of 1926, declining production and plummeting prices promoted consolidation, a trend that continued during the Depression. Operators of small mills realized that they could not continue to make a profit. In 1929 the Commerce Mining and Royalty Company built the first centralized mill in Ottawa County, west of Picher, replacing twelve existing mills. Soon afterward, north of Commerce the Eagle-Picher Company built its own central mill, at that time the world's largest, most modern lead-zinc concentrating mill. Other enterprises included Federal Mining and Smelting Company, Childers Mining Company, LaClede Lead and Zinc Company, and American Lead and Zinc Company.

The Tri-State Ore Producers' Association, founded in 1924 and headquartered in Picher, facilitated improvements in mining and smelting technology, safety practices, and health services and also monitored labor-management relations. The association provided a strong lobby in Washington and promoted lead and zinc products.

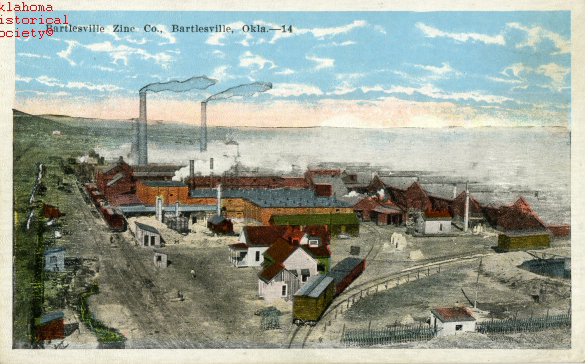

In the early years of mining, smelting (heat-refining ore into a marketable product) was conducted on a small scale at the mine site. By the 1880s and 1890s practice was to ship the concentrates to smelters in Joplin or Kansas. By that time the smelting industry, like the milling industry, had become concentrated, the most prominent company being Picher Lead Company (now Eagle Picher Company). By 1920 several smelters appeared just outside the Ottawa County section, including two in Bartlesville, two at Collinsville, one at Henryetta, and one at Sand Springs.

By 1926, the peak year of production, Ottawa County was the world's largest source of lead and zinc. From 1908 through 1930 area mines turned out a total of more than $222 million in zinc and $88 million in lead, including more than 50 percent of the zinc and 45 percent of the lead needed in World War I. After 1915 more than 90 percent of the district's ores came from the Picher field. In the late 1930s the introduction of modern mining practices, diesel trucks, and mechanized equipment reduced manpower costs and extended the field's life. In later years federal subsidies also extended production. By 1950 the total post–1908 production of the entire Tri-State District had surpassed $1 billion.

Nevertheless, mining towns began to depopulate as the principal economic underpinning deteriorated, and miners found work elsewhere. Those who stayed in the district turned to agriculture, dairying, ranching, and tourism. A few mines remained, but by the 1960s most were closed, and Eagle-Picher, the largest and longest lived enterprise, ceased production in 1967. Ghost camps, mine shafts, sinkholes, chat piles, a miners' reunion held annually in Picher, the Picher Mining Museum in the former Tri-State Producers Association building, a federal Superfund cleanup project at Tar Creek (centered at Picher), and the annual Tar Creek Fishing Tournament and Toxic Tour Bike Ride are the legacy of the district's mining activity.

Bibliography

Arrell M. Gibson, "Lead and Zinc," in Drill Bits, Picks, and Shovels: A History of Mineral Resources in Oklahoma, ed. John W. Morris (Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Historical Society, 1982).

Arrell M. Gibson, "A Social History of the Tri-State District," The Chronicles of Oklahoma (Summer 1959).

Arrell M. Gibson, Wilderness Bonanza: The Tri-State District of Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1972).

L. C. Snider, Preliminary Report on the Lead and Zinc of Oklahoma, Oklahoma Geological Survey Bulletin 9 (Guthrie, Okla.: Cooperative Publishing Co., 1912).

Samuel Weidman, The Miami-Picher Zinc-Lead District, Oklahoma, Oklahoma Geological Survey Bulletin 56 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1932).

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Dianna Everett, “Tri-State Lead and Zinc District,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=TR014.

Published January 15, 2010

© Oklahoma Historical Society