FOLKLIFE.

For more than a century folklore has been the term used for music, legends, superstitions, traditions, and customs transmitted orally from one generation to another; specifically, folk is a synonym for common people, and lore is knowledge or belief that is learned. Folklore is a term that mistakenly in the minds of many academicians and lay persons conjures an image of a little, old, pipe-smoking, bonnet-wearing granny in the mountains, washing clothes in a cast-iron pot. More specifically, folklore has been misinterpreted as songs and stories of uneducated and unsophisticated individuals seldom worthy of serious academic study. In the mid-1900s the term folklife gained popularity to describe the collection, preservation, and study of material traditions, i.e., the arts, crafts, architecture, music, legends, foods, superstitions, medicines, traditions, and customs of all people—for no matter how well educated or sophisticated they are, they carry traditional lore in some form. Oklahoma folklife reflects the traditional knowledge of an extremely diverse citizenry.

Since the late nineteenth century the United States has been recognized as the world's melting pot, but Oklahoma has been the nation's melting pot for an even longer period. As early as the 1820s the national policy and attitude was to remove American Indians to Indian Territory. By the end of the century more than five dozen tribes had been removed to what is now Oklahoma. Each had its own language, culture, and history, and many tribes found that their former enemies had become their neighbors. At the turn of the twenty-first century at least thirty-six tribes in Oklahoma were recognized by the federal government as sovereign nations; the 2000 census reported that the state's population of American Indians is the nation's second largest, with well more than sixty tribes represented. This diversity is greater than that of any other state except California.

The contrast in the state's terrain and landscape creates a natural diversity in culture and traditions. Northeastern Oklahoma reflects the physical and cultural characteristics of the Ozark Mountain region. Southeastern Oklahoma lies at an elevation of approximately 400 feet above sea level, with the exception of the Ouachita Mountains; this lower terrain has rainfall similar to the humid Gulf Coast region, has forests that support a lumbering industry and exhibits strong southern and Texas cultural influences—in fact, it is traditionally known as "Little Dixie." Following a line across to southwestern Oklahoma, the topography is a continuation of West Texas terrain, climate and culture; cattle, horses, cotton and wheat dominate the lives and cultures of its inhabitants. In northwestern Oklahoma the elevation rises to nearly 5,000 feet, and mesas rise to the sky. The area is the center of the Southern High Plains region, where wheat and cattle have been the primary crops, and both Kansas and Texas Plains cultural influences prevail. The central part of Oklahoma is an amalgam of the surrounding cultural regions. Following the Civil War the area comprised the Unassigned Lands, a place where American Indians did not reside and where they were not wanted by those who leased land or those who later settled on it.

The original settlers of Oklahoma were the Osage, the Quapaw, the Caddo, the Pawnee, the Wichita, the Comanche, and the Kiowa, but the first white settlement, Ferdinandina, occupied briefly during the late 1700s, lay on the Arkansas River in present Kay County. This French trading post apparently had little or no cultural impact. However, during the ensuing decades of fur and skin trapping and trading in the region, the French intermarried with, or at least propagated children among, American Indian groups. In 1820–21 a group of white Protestant missionaries established Union Mission on the west bank of Grand River some twenty to thirty miles above present Fort Gibson. At that time this was believed to be the nation's westernmost Anglo settlement. In 1835 the mission became the place where the first book was published in Oklahoma, and in the 1820s and 1830s numerous travelers following the Texas Road to settle in Texas stopped there for nourishment and religious renewal. This forgotten settlement did have a white cultural influence among Osage, Creek, and Cherokee.

During the same time period the Five Tribes started their westward treks, or Trails of Tears, to Indian Territory (I.T.). They left land and homes in the southern and southeastern United States. The practice of intermarriage with whites had existed for decades and among mixed-bloods and full bloods had created much political and cultural turmoil, leaving social conflicts that carried over into Indian Territory. The full bloods were opposed to removal even in defiance of the inevitable, but they had developed a loyalty to the United States government. The mixed-bloods, who were often businessmen, were loyal to the South and followed southern agricultural traditions, including slave holding. Therefore, they brought their African American slaves to the West, creating an even greater diversity. In fact, in 1848, when a Presbyterian missionary in Indian Territory heard some Choctaw slaves singing, he wrote down the words to "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot," "Steal Away to Jesus," and other spirituals. He later taught the songs to the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who brought the music worldwide popularity.

Oklahoma was the last state officially to open to non-Indian settlement; the lands were owned in common by members of each tribe and could not be purchased by anyone else. However, within some tribal boundaries non-Indians could lease land for farming and/or cattle grazing, so there came to be more white cultural influence. In 1873 coal mining became a commercial venture in the eastern area, especially in the Choctaw Nation. Because religious beliefs prevented many American Indians from going underground, Europeans were invited to enter the nation as coal miners. Strong folk traditions still flourish around the McAlester-Krebs area and are shared in the annual Italian Festival. In some areas of southeastern Oklahoma homemade Choctaw beer, known as choc, is often part of a satisfying meal. If protocol is followed, an individual can also obtain high-quality moonshine liquor in eastern Oklahoma.

White settlement started in earnest when the Unassigned Lands were opened by land run in 1889. For the next fifteen years additional runs and lotteries were used to attract settlers and to place the land into private ownership. Oklahoma became a melting pot of folk and traditional lore as ethnic and racial communities emerged. Hispanics came with the cattle drives and mining industry, and German, Polish, Russian-German and Czechoslovakian immigrant communities grew and thrived in the free lands area of central and western Oklahoma. It is possible that more people moved into Oklahoma in a shorter period than in any other migration in the nation's history.

In modern Oklahoma Hispanics comprise the fastest growing ethnic population, and Anglos and American Indians are the two largest cultural groupings. However, during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries African Americans were well represented. After the Civil War, when the slaves of the Indians were freed, they became known as Freedmen within the various Five Tribes. They often congregated into All-Black towns. When land was allotted, each member of a tribe was treated equally in the division. Nevertheless, little support could be garnered for a movement to make Oklahoma an All-Black state. Then in 1912 the "Chief Sam movement" attracted African Americans from around the nation to east-central Oklahoma, where they were supposed to pool their funds, buy a ship, and start a migration to Liberia. Both movements failed but brought numerous blacks to the state. Eventually more than fifty All-Black towns were established. Both old and new traditions were practiced, with the oldest continued among the Freedman descendants. Wild onions and eggs, sofkey (a traditional drink with different names), Indian breads, and other foods were and still are traditional among Oklahoma African Americans as well as among American Indians.

Oklahoma folklife is saturated with music. Everywhere in the state, American Indian music is performed for traditional ceremonies within each tribe, and nonceremonial music and dance is presented for non-Indian audiences. Black music has been a great influence nation wide. Funny Papa Smith, better known as the original "Howling Wolf," was living in southwestern Oklahoma when he was first recorded in the early 1930s. In the late 1920s, when dance bands became popular, the Blue Devils from Oklahoma City produced a number of influential black musicians. Among them were the legendary Charlie Christian, who changed the sounds of jazz guitar, and Jimmy Rushing, who became the major big-band blues vocalist. Tulsa's Ernie Fields Band maintained popularity for approximately forty years, and Muskogee produced jazz fiddler Claude Williams and jazz pianist Jay McShann as well as white jazz guitarist Barney Kessel. The music tradition extends into "barbershop harmony," for the national organization for this musical style, the Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barber Shop Quartet Singing in America (SPEBSQSA) was formed in Tulsa.

Even though it is known as the "buckle on the Bible Belt," Oklahoma is one of the "dancingest" states in the nation. There was a time when dance halls dotted the countryside, and citizens danced all Saturday night and prayed all Sunday morning. There were and still are more churches than dance halls, but the dancing crowds numbered from a few couples to 2,500 or more individuals. The music that attracted most of them was Western swing, but ethnic diversity is also found in dance halls. For example, Czech Halls still operate in central Oklahoma and offer both traditional Czech music and modern music for dancing.

Sacred music has also been a major tradition. In the nineteenth century "shape-note singing" spread from the northeastern states into the South and then was introduced among the Five Tribes. The style was then taught to Indian Freedmen, and two large singing conventions emerged from the Freedmen experience. Singing schools became a tradition, and as the white population increased, so did the popularity of singing schools, fifth Sunday singings, and all-night singings. Family singing groups and American Indian quartets became common at those events. Albert Brumley, "dean of gospel song writers," who wrote such classics as "I'll Fly Away," was born in eastern Oklahoma. He grew up attending singing schools. He wrote hundreds of gospel songs for songbooks published by Vaughn and Stamps-Baxter firms as well as for his own publishing company, and his songbooks were used by singing groups, singing schools, and singing conventions across the state. It is well known that an individual's reaction to a religious conversion varies by racial, ethnic, and other backgrounds, but when an African American blues man was or is "called by God," he sets aside the blues, or Satan's music, forever, and his voice becomes an instrument of and for the Lord. Thus, both the church and the dance hall have been major traditional cultural influences throughout Oklahoma.

Over the decades the fiddle has been a dominant instrument among Anglo Americans, African Americans, Hispanics, and American Indians. Although traditional fundamentalists condemned the fiddle as "the Devil's instrument," that belief is no longer universal and now applies mainly to using the fiddle to play dance music. Fiddling contests are numerous; over the years a contest style known as the Texas-Oklahoma style became the winning method of playing. It combines Western-swing fiddling, in which the fiddler slows the tempo and uses most of the bow, with the older traditional tunes and a few later Western-swing numbers. There are those who fiddle the old-time way, using the upper third of the bow in a short, rapid "breakdown" rhythm; yet, the hybrid Oklahoma fiddler has the ability to play almost any style. Western-swing fiddlers and jazz fiddlers have similar styles of bowing. The guitar, played with open chords, has been the traditional backup instrument for fiddlers and is also an important instrument in dance bands. The Western-swing rhythm guitar style, developed during the late 1930s in Tulsa by Eldon Shamblin while he was a member of the band called Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, has spread throughout the world. The four-string banjo was a popular rhythm instrument in dance bands until it was replaced by the guitar, but the five-string banjo, a traditional instrument, was not heard with frequency until bluegrass music entered the state in the 1970s.

Western-swing music is dance music played by string bands, with horns added in some bands. This music's strength, drive, and popularity come from a strong fiddle section combined with other stringed instruments. It evolved from cowboys' love of dancing. Ranch-house dances were common in West Texas and Oklahoma, but farm families were often more socially conservative and driven by church morality that forbade dancing. Play-parties were their form of dancing. Cowboys enjoyed holding the hand of a female and putting a hand on her waist and guiding her across the floor in a dance rhythm. One cotton-farming, fiddling family, the Wills family, who lived near Memphis, Texas, enjoyed playing for ranch dances. In 1929 the oldest child, Bob Wills, joined with guitarist Herman Arnspiger to play for parties and house dances in Fort Worth. When singer Milton Brown joined them, they became the legendary Light Crust Doughboys. In late 1933 Bob Wills organized his own band and included his brother, Johnnie Lee Wills. Forced out of Texas, they went to Tulsa. The career of Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys blossomed, and Western swing grew to maturity. Since then, Oklahoma has produced most of the legendary Western-swing musicians and has attracted numerous outstanding artists to work in the major bands. For many years the state was the home base for most of the great Western-swing bands. There were and are Western bands that are labeled as Western swing, but if they did not or do not play for dances, they are not Western swing—they are Western-string bands.

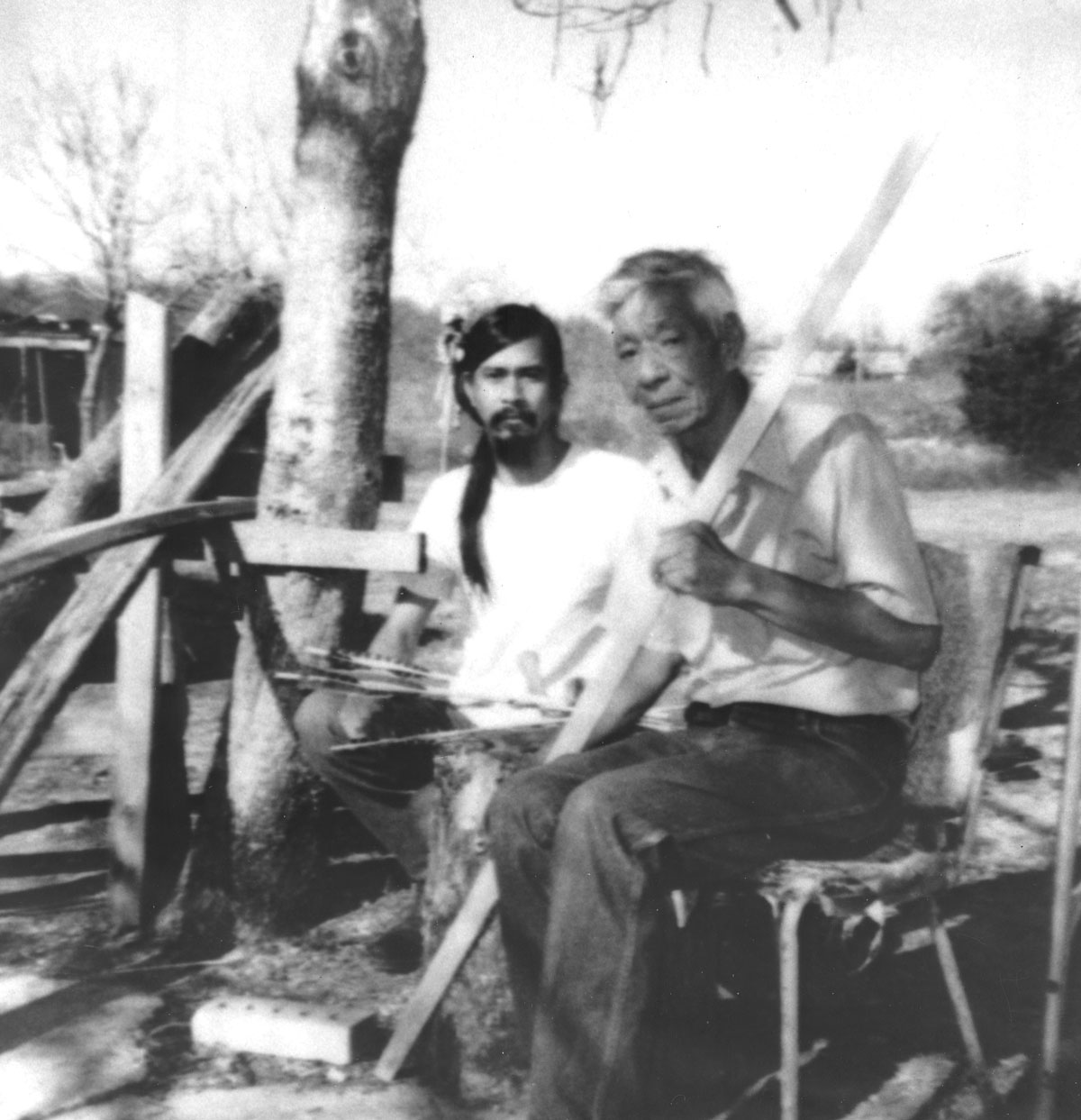

Occupational cultures comprise another category of collective experience in Oklahoma's folklife history. For example, the livestock industry created forms of traditional life, and as the industry spread throughout Indian Territory, it became a natural occupation with American Indians. Although depicted by Hollywood and in Western fiction as having inalterably conflicting lifeways, cowboys and Indians were not at odds in Oklahoma, for they often were the same people. Ranchers, working cowboys, and rodeo hands still contribute to the richness of the state's folklife.

The petroleum industry has played a major role in Oklahoma's financial and cultural growth. However, only a few individuals have seriously attempted to collect and preserve the folklife of the roughneck, the driller, the pipeliners, and other petroleum workers; instead, most attention has been directed toward individuals who gained legendary wealth and companies that were organized in the state. The limited interest in the folklife of the oil industry may due to the fact that it was a "boom or bust" endeavor and that its work force was generally migratory, moving from one oil strike to another. But then the Oklahoma economy, at least until recent years, has itself been "boom or bust," with land, livestock, oil, cotton, and wheat as primary industries.

Houses and barns in Oklahoma have been as varied as the terrain. Houses were often designed and built to serve families working in a specific occupation. In oil-boom towns and even in the oil fields, "shotgun shacks" were constructed for workers with families; the name came from the belief that a shotgun could be fired in the front door with the buckshot exiting the back without hitting anything in the house. One of the oldest surviving buildings is a log cabin (Sequoyah's Cabin near Sallisaw), and in western Oklahoma a sod house (the Sod House Museum at Aline) has been preserved as a reminder of the early settlers' life and survival skills. Houses were designed and constructed to utilize natural resources such as sandstone, available in many eastern Oklahoma areas, and limestone, found in other regions. Many of these prestatehood buildings are still occupied, as are some houses that were constructed from rocks gathered on the owner's property. Barns were designed and built for functional uses; perhaps the most unusual is the circular barn near Arcadia, which was built to withstand tornados. The most traditional methods of construction are still found among the Amish, who use wooden pegs and careful jointing to provide greater strength and durability than fasteners such as nails and screws. An example can be seen near Oologah on the Dog Iron Ranch, Will Rogers's birthplace.

Outlaw lore is another hallmark of Oklahoma folklife. Numerous legends have circulated, particularly about outlaws such as the Daltons, Belle Starr, and Charles Arthur "Pretty Boy" Floyd. One of national significance has slowly been put away in the memories of only a few. It is "the Enid-Booth Legend." On January 13, 1903, an Enid house painter named David E. George committed suicide at the Grand Avenue Hotel; before moving to Enid, Oklahoma Territory, he had been known as John St. Helen and worked as a bartender in Granbury, Texas. Before his suicide he confessed to being John Wilkes Booth, the man who had assassinated Pres. Abraham Lincoln. Much research has been conducted in order to refute or verify his claim, but neither side has proved a case. His body was put on display in Enid before being sold for use in carnival exhibits.

Folk medicine, a necessity to rural families living far from medical care, includes family cures for ills and aches as well as American Indian medicines and practices. In recent years some of these have been accepted as valid. One well-known treatment, not a cure, was to allow bees to sting the hands of individuals suffering from arthritis; some specialists now practice the injection of bee venom as a therapeutic method. However, perhaps the most controversial or at least unusual folk cure is the "madstone," a stone believed to have almost supernatural power to draw the poison from rabid animal bites and believed to be the only way to prevent the victim from contracting hydrophobia and dying. Madstones were and still are found in use throughout the nation, not just in Oklahoma. Most madstones are handed down in families as a treasured item, and early records indicate that some were brought from the British Isles during the state's early settlement days. An occurrence in the year 1914 is exemplary: A young girl in Yeager was bitten by a rabid dog. When a madstone could not be found, all of her schoolmates marched to her house to wave "goodbye" at her bedroom window. She was subsequently taken by train to Little Rock, Arkansas, where a doctor gave her shots, and she survived.

Perhaps Oklahoma's most negative reputation lies in the migration that accompanied the Dust Bowl era. Southern states have been noted for their "rednecks" and "crackers," both derogatory terms for poor, generally uneducated or at best undereducated, people involved in farming or cattle raising, living rural lifestyles, and having crude manners. All states have rednecks or individuals who fit that description; they are not limited to the South. Crackers, on the other hand, were usually poor southern white farmers (African Americans referred to all white people as crackers). However, Oklahoma's crackers became known as "Okies," sometimes spelled "Oakies," who migrated mainly to California during the Dust Bowl days of the 1930s. The migration had nothing to do with the dust storms, and the migrants were not families from surrounding states who purchased auto tags in Oklahoma where tags were supposedly cheaper (Oklahoma had higher tag taxes than the adjacent states).

The Okies, who numbered in the hundreds of thousands, were mostly sharecroppers or tenant farmers who were forced from their cotton farms not by the banks, as many believe, but by the farmers who owned the land. In the late 1920s and 1930s American-grown cotton had no market value, not because of the Great Depression but because of a lack of demand for short-fiber cotton. The U.S. Agriculture Department's crop reduction program, designed to help farmers, actually helped owners. Sharecroppers' and tenant farmers' crops were plowed under, forcing them to migrate westward in search of a way to make a living.

The seven or eight northwestern Oklahoma counties affected by the Dust Bowl were sparsely populated and lost very little population in the 1930s. The Okies migrated from eastern and southern Oklahoma. In western states "Okie" became a four-letter, derogatory term synonymous with all Oklahomans. Many Oklahomans continue to resent being called "Okie."

During that era native son Woody Guthrie, born in Okemah in 1912, became known as the "Oklahoma Dust Bowl Balladeer." However, the Dust Bowl was hundreds of miles northwest of Okemah. He gained his Dust Bowl experience by living in Pampa, Texas, and he wrote his songs about Texas storms. (Guthrie did know many Okies, and they helped inspire his migrant songs.)

As one of the youngest states in the nation, Oklahoma has paid little attention to its folk and traditional cultures and contributions. Change came in 1982 as the state commemorated its Seventy-fifth Statehood Anniversary, or Diamond Jubilee, and Oklahoma was featured at the Smithsonian Institution Festival of American Folklife. Folk musicians and artists—white, American Indian, African American, Hispanic, and other ethnic representation—cooperated to make the states diversity known to the rest of the world. They made it one of the most successful and popular festivals ever produced by the Smithsonian Institution.

See Also

ARTS AND CRAFTS–AFRICAN AMERICAN, CULTURAL REGIONS, FOLK ARCHITECTURE, FOLK ART, FOLK BELIEFS, FOLK GAMES, FOLK MEDICINE, FOLK MUSIC, FOLK NARRATIVE AND LORE, FOODWAYS, IMMIGRATION, RECREATION AND ENTERTAINMENT, TRADITIONAL ARTS–AMERICAN INDIAN

Bibliography

Benjamin A. Botkin, "The American Play-Party Song: With a Collection of Oklahoma Texts and Tunes" (Ph.D. diss., University of Nebraska, 1931).

Benjamin A. Botkin, Folksay: A Regional Miscellany, 4 vols. (Norman: Oklahoma Folk-lore Society and University of Oklahoma Press, 1930–32).

Benjamin A. Botkin, Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1945).

Benjamin A. Botkin, ed., A Treasury of American Folklore: Stories, Ballads, and Traditions of the People (New York: Crown Publishers, 1944).

Benjamin A. Botkin, ed., A Treasury of Southern Folklore Stories, Ballads, Traditions, and Folkways of People of the South (New York: Crown Publishers, 1949).

Benjamin A. Botkin, ed., A Treasury of Western Folklore (New York: Crown Publishing, 1951).

Jan Harold Brunvand, ed., American Folklore: An Encyclopedia (New York: Garland Publishing, 1996).

Jan Harold Brunvand, The Study of American Folklore: An Introduction (4th ed.; New York: Norton, 1998).

Richard M. Dorson, ed., Folklore and Folklife: An Introduction (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972).

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Guy Logsdon, “Folklife,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=FO012.

Published January 15, 2010

© Oklahoma Historical Society