TRANSPORTATION.

Traveling within and across Oklahoma involved three modes of transportation: land, water, and air. Each of these means of moving people and goods from one place to another underwent an evolutionary process. Trails became highways, rivers emerged as interstate waterways, steam-powered railroads gave way to high-speed diesel trains, and air travel evolved from an expensive experiment to a commonplace convenience. Three elements provided the primary impetus for change: Individual initiative, technological innovation, and government policy.

Afoot or on horseback the first Oklahomans opened routes across the region. Following the line of least resistance or existing animal tracks, American Indians established trails that afforded them access to food, trade, and enemies. The Black Dog Trail and the Osage Trace conveyed hunters and warriors to game and to their enemies. On the vast western prairies the Wichita Indians followed trails to the encampments of their customers, the Comanche. When non-Indians arrived, they found an established system of paths and trials crisscrossing the region. In the 1820s immigrants traveling southward to Texas followed the Osage Trace to the Arkansas River and then forged a wagon road to the Red River. Renamed the Texas Road, this wilderness highway emerged as the most important north-south route in the region. Today U.S. Highway 69 approximates the route of the Texas Road.

The arrival of the U.S. Army, Indian emigrants, and cattlemen introduced new dimensions to overland travel. In 1826 Lieutenant James L. Dawson led a party of men who built the first surveyed road in Oklahoma, the fifty-mile-long Fort Gibson–Fort Smith military road. As this practice continued, military roads became the principal routes for communication, supply, and moving people. In the 1830s and 1840s federal officials removed the Five Tribes to Indian Territory. Once the tribes reestablished their governments, they enacted legislation dealing with overland travel. Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Creek officials began the practice of granting concessions to their constituents. By 1870 turnpikes, toll bridges, and ferries covered the entire length of the Texas Road. After the Civil War cattle trails became an important feature of overland travel. From the 1860s through the 1880s thousands of head of beef came up the Chisholm and Great Western trails from Texas to railheads in Kansas and Nebraska. Today, U.S. Highway 81 approximates the route of the Chisholm Trail.

Emergence of the state of Oklahoma spawned changes in overland travel. Territorial legislators enacted statutes that restricted public-road rights-of-way to section lines and delegated responsibility for construction and maintenance to county commissioners. But farmers and others frequently battled mud, washouts, and bank-full streams in their travels. In 1902 A. C. Titus organized the first good roads association in Oklahoma. A national movement sponsored by railroads and the federal Office of Public Roads, good-roads advocates campaigned to get farmers out of the mud. A territorial organization emerged, and in 1906 at the Oklahoma State Constitutional Convention members secured provisions for a state highway department. In 1911 the Oklahoma State Highway Department began to function, but the agency received no authority or funds to build and maintain highways. In 1916 Congress passed the first Federal Aid Highway Act, providing matching grants to states for road improvements. State legislators appropriated funds to obtain the federal money, all of which went to county commissioners.

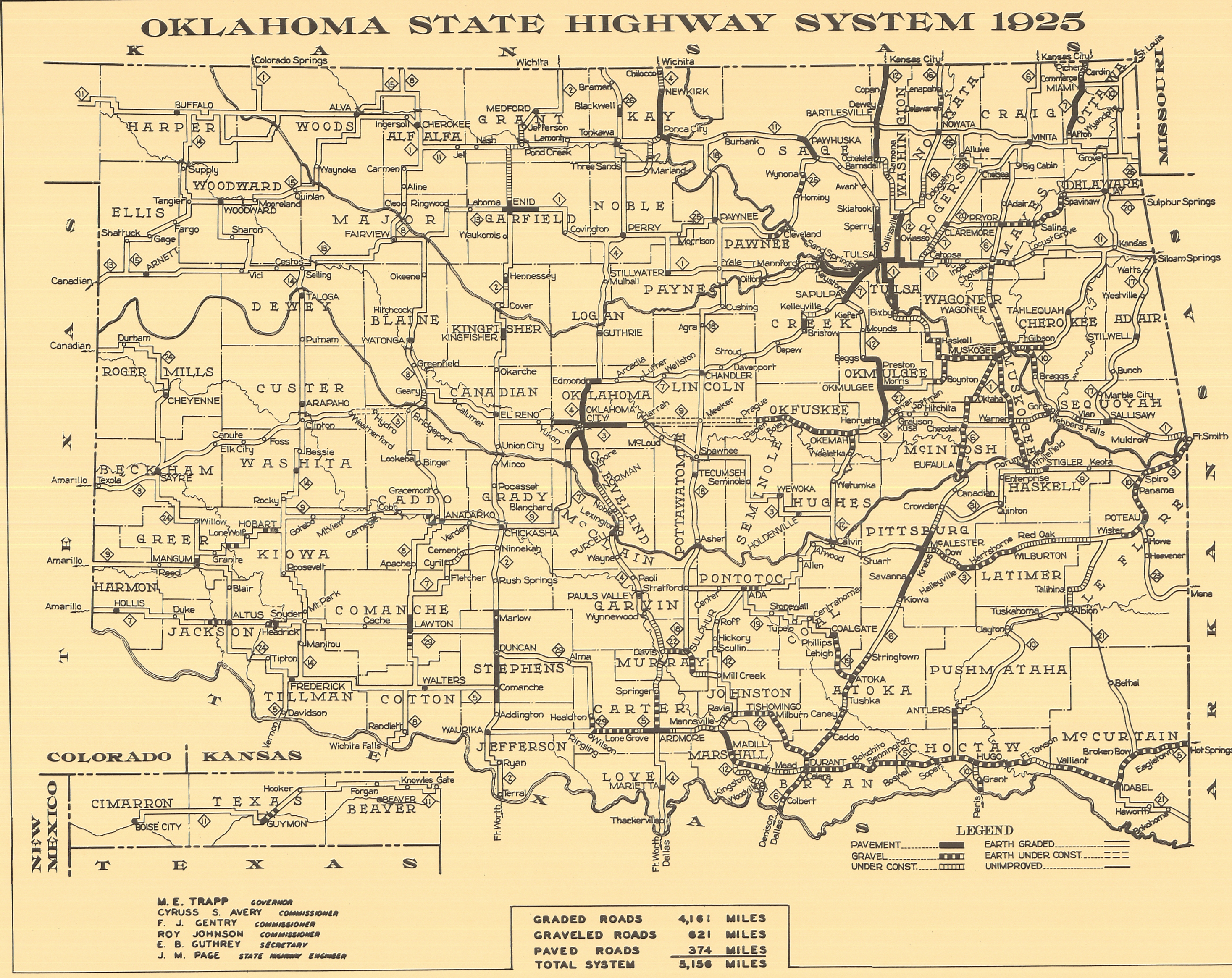

In the 1920s road building and maintenance became a significant responsibility of state government. Automobiles quickly emerged as a necessity for Oklahomans. The number of vehicles registered in the state jumped from 127,000 in 1918 to 500,000 in 1926. Moreover, federal authorities demanded accountability from state officials for funds they received, requiring a fully functioning highway department. In 1924 Gov. Martin E. Trapp led good-roads advocates in securing legislation establishing a state highway system, assigning construction and maintenance responsibilities to the department, creating a state highway commission, and enacting a gasoline tax. In addition, officials from state highway departments across the country cooperated with federal authorities to create the U.S. Highway System. Directly as a result of the efforts of Cyrus Avery of Tulsa, conferees designated nine U.S. highways in the Sooner State. These measures provided the foundation for a modern state highway system.

In the years following World War II the state embarked on a program to build superhighways. In 1947 business leaders from Tulsa and Oklahoma City convinced Gov. Roy J. Turner to sponsor legislation to construct a turnpike between the two cities. Turner succeeded. The eighty-eight-mile-long Turner Turnpike opened in the spring of 1953. Traffic and revenue exceeded the most optimistic estimates, fostering a commitment to toll road construction. By the end of the twentieth century Oklahoma had ten turnpikes, operated by the Oklahoma Turnpike authority and comprising more than six hundred miles of tollways, the most extensive system in the nation. Federal initiatives brought additional superhighways to Oklahoma. In the late 1950s contractors began building Interstate Highway 35, a north-south artery, and Interstate Highway 40, an east-west route, completing both roads by the end of 1975.

Throughout its existence the state highway department, renamed the Department of Transportation in 1976, endured challenges and enjoyed successes. The agency frequently faced inadequate funds for the responsibilities delegated to it, experienced political manipulation, coped with a deep-seated patronage system, and endured occasional scandal. But the mileage of paved roads increased from three hundred in 1924 to twelve thousand in 1970. Innovations in construction techniques, planning, and equipment enabled the creation of a modern system of public roads for Oklahoma.

Waterborne transportation emerged when Indians employed their ingenuity to make watercraft. Dugout canoes, or pirogues, fashioned from cottonwood trees, rafts, and bull boats, waterproof bison hides stretched over a round frame of saplings, made possible travel on Oklahoma's waters. When the first Europeans arrived, they quickly adopted the dugout canoe. French traders in cottonwood pirogues plied the waters of the Arkansas and Red rivers. The French probably introduced the keelboat, and by the early years of the nineteenth century crews cordelled, poled, and warped these sturdy craft along the major watercourses of Indian Territory.

Advances in technology helped breech the isolation of frontier Indian Territory. In 1824 the Florence became the first steamboat to navigate the Arkansas River to Fort Gibson, inaugurating commercial river navigation in Oklahoma. Service on the Arkansas expanded as emigrant tribesmen established farms and plantations. During the shipping season steamships carried people and agricultural commodities from twenty-two landings along the Arkansas in Indian Territory into the bustling commerce of the Mississippi River valley and on to New Orleans. Returning steamers conveyed passengers and manufactured goods to frontier villages and farmsteads. However, as railroads expanded into eastern Indian Territory, commercial traffic on the Arkansas River diminished.

During the first decades of the twentieth century business leaders in Tulsa reinvigorated the concept of Arkansas River navigation. They fostered a vision to make their burgeoning city the head of navigation on the river and promoted their cause as crucial to the region's economic development. Beginning in 1916 Clarence B. Douglas, executive director of the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce, worked to secure legislation authorizing studies of the concept by the Army Corps of Engineers. In 1934 Newton R. Graham, a Tulsa banker, succeeded Douglas as the chief proponent of Arkansas River navigation. He tirelessly lobbied congressman, worked with regional organizations, and cajoled state leaders to support the project. In 1949 Graham gained a powerful ally when Robert S. Kerr became a member of the U.S. Senate. Kerr built political alliances to secure passage of legislation to construct flood control projects and a river navigation system. Although neither man lived to see completion of the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System in 1971, their initiative and determination provided a lasting legacy for interstate commerce and economic development.

Commercial navigation developed on the Red River in the 1830s. Because of the Great Raft, a huge logjam that clogged the river in northwest Louisiana, vessels could not expeditiously ascend the Red River to Indian Territory. Nevertheless, intrepid steamboat captains found cutoffs and looped through bayous to bypass the obstruction. In 1831 the first steamboat reached the Red River settlements in Indian Territory, fostering economic development. Cotton from plantations owned by Chickasaw and Choctaw mixed-bloods moved downstream to Shreveport and other commercial centers. By 1853 steamboats stopped at more than twelve landings in Indian Territory along the Red River. In 1873 engineers succeeded in permanently opening a channel through the Great Raft. Steamboating flourished, reaching its peak in 1884, as agricultural commodities, people, and finished products moved along the river. During the last decade of the nineteenth century railroads constructed tracks parallel to the Red. Traffic on the waterway quickly diminished, and by 1920 commercial use ceased.

More than any other mode of transportation, railroads demonstrated the significance of government policy, technology, and individual initiative. After the Civil War ended, federal officials secured rights-of-way from each of the Five Tribes. Concluded between March and July of 1866, all of the Reconstruction treaties contained provisions granting railroads access to Indian land. Tribal officials agreed to accommodate one north-south and one east-west railway. Indian leaders did not oppose the railroad specifically, but they failed to obtain terms they believed adequately compensated the tribes for this intrusion. Lobbyists for the railroads and promoters of other business interests in Washington, D.C., prevailed.

Construction began in 1870 when crews of the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railway Company (MK&T, or Katy) laid the first track in Indian Territory into the Cherokee Nation south of Chetopa, Kansas. By December 1872 the line reached Denison, Texas, completing a north-south route in Indian Territory. In September 1871 the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Company (A&P) entered the northeast corner of the Cherokee Nation and headed west. Because of financial difficulties, the line did not push beyond Vinita until the 1880s, and then as the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway Company (Frisco). Efforts to build other railroads across Indian Territory failed as tribal leaders continued to insist upon negotiated contracts for each right-of-way. In 1882 Congress passed legislation extending eminent domain to Indian Territory. This action, coupled with a rapidly growing national economy, produced an explosion of railroad building.

Large interstate corporations as well as locally operated companies crisscrossed Indian and later Oklahoma territories with steel rails. At the turn of the century nine trunk lines carried goods and people from and through the Twin Territories to destinations in surrounding states. Branch and short-line operations spread like a spider web across the state, making connections to main line carriers. By 1910 six thousand miles of rails crossed the hills, prairies, and plains of Oklahoma.

Between 1910 and 1930 a more deliberate form of rail-road development occurred. The exploitation of a variety of natural resources required enlarging the rail system in the state. Entrepreneurs responded by constructing lines to oil fields, coal mines, timber tracts, as well as western farm and ranch land. These developments made possible connections to processing centers and markets for raw materials.

Construction of a railroad network directly affected the economy of the state. Capitalists from the Midwest and the East invested in railroad stock and other securities. Foreign investors, particularly from Belgium, France, and the Netherlands, eagerly bought shares in Oklahoma railroads. Other developers tapped local resources. Charles N. Haskell and William Kenefick obtained cash and land grants from the communities along railroads they built, and they sold land at townsites they promoted. At Cheyenne and Beaver, local merchants, farmers, and ranchers pooled resources to build rail connections to their towns. Some of these investments paid handsome dividends, while other investors lost money.

The technology of the steam locomotive changed life for Oklahomans. Trains moved as far in an hour as a horse and buggy traveled in a day. Construction techniques made railroads oblivious to most geographical obstacles, bridging rivers, crossing mountains, and conquering the endless plains. Trains operated night and day, and, for the most part, were immune to the whims of nature. Railroads fostered urbanization as towns large and small emerged along the rights-of-way. Other towns ended an isolated existence when rails and the accompanying steam engine surged into their city limits. Occasionally, residents moved an entire town a mile or more in order to be closer to a rail line.

Beginning in the 1930s railroads in Oklahoma underwent significant changes. Abandonments and bankruptcies eliminated service to some communities or fostered consolidation of railroad companies. This trend continued into the 1970s. Familiar heralds disappeared from rolling stock as the Missouri, Kansas and Texas, the Missouri Pacific, the Frisco, and in 1984, the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific ceased to operate. Larger companies took their place as the Union Pacific and Burlington Northern–Santa Fe became the major interstate carriers. Passenger service quickly declined, finally ending in the 1960s. Technological advances changed the motive force for railways. Beginning in 1946 carriers operating in Oklahoma replaced steam engines with diesel-electric locomotives. Faster, more fuel efficient, and much more powerful, diesel engines superseded their black smoke–belching predecessors.

During the last decades of the twentieth century railroads remained a significant part of the state's transportation system. Major interstate carriers continued to provide service to Oklahoma. Short-line railroads, such as FarmRail and the Kiamichi Railroad, emerged to provide service to rural areas and small towns that larger companies ignored. By 2000 twenty-two railroad companies provided the Sooner State with interstate and intrastate rail service on about half of the mileage of track that had existed a century earlier.

Perhaps more than any other form of transportation, the acceptance of air travel involved individual initiative coupled with technological advances. Seven years after the Wright brothers' initial flight, the first airplane flew in Oklahoma. In 1910 crowds gathered in Oklahoma City to witness their first glimpse of a flying machine. These flimsy new devices attracted in particular the attention of newspaper writers. Eugene Lorton, publisher of the Tulsa World, and Walter M. Harrison, managing editor of the Daily Oklahoman, regularly informed readers of the potential for aviation. Their columns promoted air travel and helped readers recognize airplanes as more than a passing fancy.

In the 1920s leaders in the state's petroleum industry further enhanced the public's understanding and potential of commercial aviation. Frank and L. E. Phillips as well as William G. Skelly became avid proponents of aviation. Motivated in part by the desire to expand the market for newly developed aviation fuel but also recognizing the speed and convenience that air travel promised, they sponsored flying exhibitions, races, and air shows. Following the spectacular success of Charles Lindbergh's trans-Atlantic solo flight in 1927, oil industry executives enlarged their efforts to promote aviation as the future solution to expedient, safe, long-distance travel.

Public personalities with Oklahoma roots joined in the promotion of air transportation. Will Rogers, one of the best-known Americans and certainly the best known Oklahoman of the era, received the title of "Aviation's Patron Saint." In his newspaper columns, radio broadcasts, and public appearances Rogers frequently trumpeted the advantages of air travel by emphasizing its safety, speed, and convenience. Wiley Post complemented Rogers' promotional activities. His daring exploits as well as his role in developing new technology contributed immeasurably to expansion and acceptance of commercial aviation.

Oklahoma entrepreneurs entered the air-travel business in its infancy. In the late 1920s Tom E. and Paul R. Braniff founded Braniff Airlines to provide scheduled passenger service between Oklahoma City, their headquarters, and Tulsa. By the time they moved their business to Dallas in 1942, Braniff Airways carried passengers to international destinations. In 1929 Erle P. Halliburton founded S.A.F.E.way Airline. Halliburton introduced low fares to compete directly with passenger railroads. Experimental business ventures emerged in Oklahoma as well. In 1929 and 1930 Waynoka served as a major terminal for Transcontinental Air Transport. Travelers flew on Ford Tri-Motor airplanes, including the City of Waynoka, in and out of this small northwestern Oklahoma town, where they transferred to the Santa Fe railroad. Following World War II federal officials encouraged the growth of air travel by providing subsidies to regional carriers for scheduled flights to small cities. This policy fostered the organization of Central Airlines in Oklahoma City, a successful feeder carrier that eventually operated in six states until the late 1960s.

During the later decades of the twentieth century the industry experienced consolidation and bankruptcies that extinguished most airlines with Oklahoma ties. However, the aviation industry remained a major, vital element in the state's economy. Aside from scheduled air service at three major airports, auxiliary facilities significantly contributed significantly as employers and corporate taxpayers. In 1946 the American Airlines Maintenance and Engineering Center opened in Tulsa. The largest facility of its kind in the world, the center is the primary nongovernment employer in the state. At Oklahoma City, the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center trains air traffic controllers and administers an aviation medicine program. From the first sputtering Curtiss biplane launched in 1910 to the jumbo jets of the late twentieth century, Oklahomans pioneered, promoted, and prospered from the aviation industry.

Today Oklahomans readily drive across the state on modern highways, conveniently fly to numerous destinations, as well as enjoy the availability of rail and waterway transportation. Many people benefit from these modes of moving from one place to another, but few appreciate or understand how they developed. Because of individual initiative, technological innovation, and government policy, travel and transportation in the Sooner State became a commonplace convenience.

See Also

AIRPORTS, FERRIES AND FORDS, HIGHWAYS, RAILROADS, STEAMBOATS AND LANDINGS

Bibliography

Ray Allen Billington, Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier (New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., 1974).

Kareta G. Casey, "Wiley H. Post's Around the World Solo Flight," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 55 (Fall 1977).

William P. Corbett, "Oklahoma's Highways: Indian Trails to Urban Expressways" (Ph.D. diss., Oklahoma State University, 1982).

R. E. G. Davies, A History of the World's Airlines (London: Oxford University Press, 1964).

Michael J. Hightower, "The Riverboat Frontier: Early-Day Commerce in the Arkansas and Red River Valleys," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 89 (Summer 2011).

Donovan L. Hofsommer, "Oklahoma Railroad Maintenance Authority: An Example of Rural Pressure Group Politics," Journal of the West 13 (October 1974).

Donovan L. Hofsommer, ed., Railroads in Oklahoma (Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Historical Society, 1977).

Bradford Koplowitz, "The Rock Island Line is a Mighty Good Line—to Research," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 66 (Summer 1988).

John J. Nance, Splash of Color: The Self-Destruction of Braniff International (New York: William Morrow Company, 1984).

Railroads of Oklahoma, June 6, 1870–April 1, 1978 (Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Department of Transportation, 1978).

Donovan Reichenberger, "Wings Over Waynoka," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 65 (Summer 1987).

Fred Roach, Jr., "Vision of the Future: Will Rogers' Support of Commercial Aviation," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 57 (Fall 1979).

William A. Settle, Jr., The Dawning of a New Day for the Southwest: A History of the Tulsa District Corps of Engineers, 1939–1971 (Tulsa, Okla.: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1975).

Keith Tolman, "Business on the Wing: Corporate Sponsorship of Oklahoma Aviation, 1927–1935," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 66 (Fall 1988).

Keith Tolman, "Printing Ink and Flyingwires: Oklahoma Journalism and the Promotion of Aviation," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 72 (Spring 1994).

Keith Tolman, "Tea Kettle on a Raft: A History of Navigation on the Upper Red River," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 81 (Winter 2003–04).

Carl N. Tyson, The Red River in Southwestern History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1981).

Augustus J. Veenendaal, Jr., "Railroads, Oil, and Dutchmen: Investing in the Oklahoma Frontier," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 63 (Spring 1985).

Thomas A. Wikle, "Transcontinental Crossroads: Oklahoma's Lighted Airways in the 1930s," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 88 (Fall 2010).

Muriel H. Wright, "Early Navigation and Commerce Along the Arkansas and Red Rivers in Oklahoma," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 8 (March 1930).

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Bill Corbett, “Transportation,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=TR006.

Published January 15, 2010

© Oklahoma Historical Society