The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

BOOMER MOVEMENT.

After the Civil War, in 1866 the U.S. government undertook the making of new treaties with many of the nation's Indian tribes, some of whom had fought on the side of the Confederacy. Among these were the Creek and Seminole tribes of Indian Territory. These two groups, which had earlier been forcibly removed from their native homelands in Georgia and Florida, had been assigned land that extended across much of present central Oklahoma. As a result of the 1866 treaties the Unassigned Lands, two million acres lying in a north-south strip in the heart of Indian Territory, were left unattached to any Indian tribe. The Unassigned Lands came to public attention when Elias C. Boudinot, a Cherokee citizen then working as a railroad lobbyist in Washington, D.C., published an article on the subject in the February 17, 1879, issue of the Chicago Times.

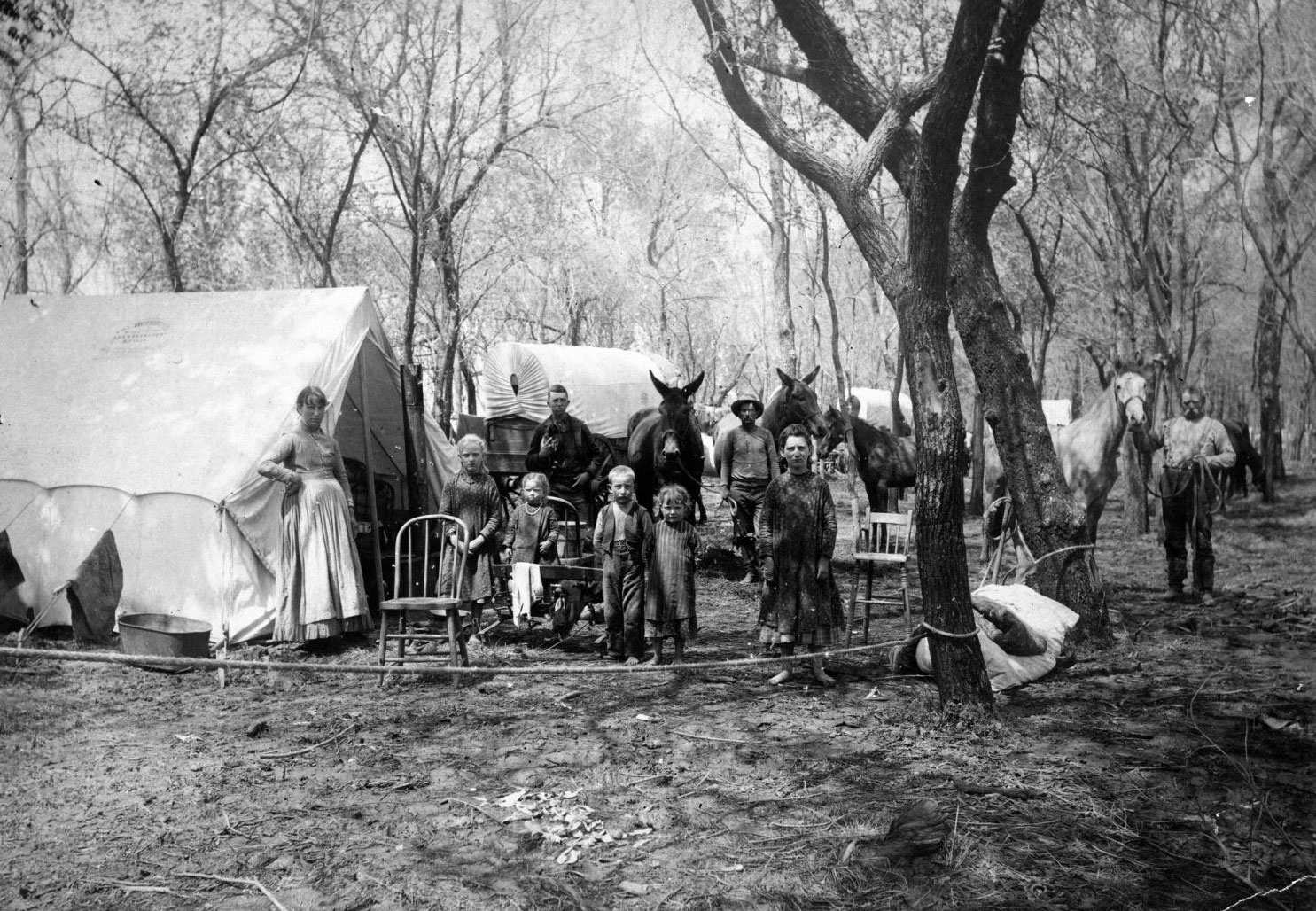

Dr. Morrison Munford of the Kansas City Times took special interest in the matter and began publicizing the idea of white settlement in the region, which had become known popularly as the "Oklahoma Lands" following previous efforts to establish the territory as a new, Indian "State of Oklahoma." Munford was first to use the words "boom" and "boomers" to describe the phenomenon. Shortly after the publication of the Chicago Times article, in May 1879 James Madison Bell, a Cherokee, tried to settle in the Cherokee Outlet, and a man known only as "Captain Sears" also tried to settle in the Oklahoma Lands. At the same time, with Morrison Munford's backing Col. Charles C. Carpenter, a Kansan who had earlier promoted white intrusion into the Black Hills of South Dakota, recruited a following of Kansas and Missouri settlers for a colonizing effort. Although Carpenter did not accompany them, his wagon train of colonists entered Indian Territory from Coffeyville, Kansas, and attempted to establish a settlement on the North Canadian River.

This initial effort began the Boomer Movement. U.S. troops and federal officials quickly evicted the intruders. But it was by no means the last of the matter. The cause was then taken up by David Lewis Payne, a Wichita, Kansas, pioneer settler and politician who was then working in Washington, D.C., as an assistant to the doorkeeper of the House of Representatives. Inspired by Boudinot, Payne returned to Wichita in August 1879 and supported by his common-law wife, Rachel Anna Haines, began recruiting followers for his first intrusion into the Unassigned Lands.

In late April 1880 Payne led a party of twenty-one men from Wichita to the site of present Oklahoma City. There on the south bank of the North Canadian they laid out a town called Ewing and relished their new settlement until Lt. George H. G. Gale arrived with a troop of Fourth Cavalry and took them under arrest to Fort Reno. After being held there for a short time, the boomers were escorted back to Kansas.

Payne was not intimidated by his arrest or by Pres. Rutherford B. Hayes's April 26, 1879, proclamation forbidding unlawful entry into Indian Territory. Claiming he was anxious to be arrested and have the issue of settlement in the Unassigned Lands tested in court, Payne organized a larger group and returned to the Ewing site in July. Again his contingent were arrested, escorted to the Kansas line, and set free without going to court. In March 1881 the government prosecuted Payne at Fort Smith, Arkansas, before Judge Isaac Parker, who ruled against the Boomer leader. The only legal action that could be brought against Payne was a federal law levying a thousand-dollar fine for a second intrusion into Indian Territory. Payne, however, had no money or property against which the fine could be assessed. News of his arrest only made him more popular on the frontier and further publicized his cause.

Payne continued to enlist boomers. A June 1884 settlement venture at Rock Falls in the Cherokee Outlet turned out disastrously for him when in August the U.S. Army burned his buildings, confiscated his Oklahoma War Chief press, and took him on a punishing wagon journey overland to Fort Smith. During the trip he and his men were taken to the Cherokee Nation and paraded through the streets of Tahlequah, past the Indian populace who despised Payne for his efforts to seize part of their tribal haven in Indian Territory. On two occasions Payne journeyed to Washington, D.C., to lobby Congress on the issue of settling the Unassigned Lands. He also applied himself to swaying the frontier press of Kansas, and he often addressed huge crowds of admirers. After a speech at Wellington, Kansas, Payne died suddenly on November 28, 1884, of heart failure.

Although Payne's demise temporarily set back the Boomer Movement, Payne's lieutenant, William L. Couch, assumed leadership. Couch led four intrusions, one in mid-winter 1884 to the site of present Stillwater. Once again, the U.S. Army arrested the boomers and drove them back to Kansas. Another Couch-led expedition to the North Canadian in October 1885 also resulted in expulsion and brought an end to the boomer intrusions.

During 1886 and 1887, however, the boomer cause gained new momentum when the Santa Fe Railway constructed a line that ran from Arkansas City, Kansas, directly through the heart of the Unassigned Lands to Gainesville, Texas. Couch and followers such as Samuel Crocker, editor of the boomers' Oklahoma War Chief newspaper, began working on the political aspect of opening the region to settlement. Rep. Sidney Clarke of Kansas and Sen. James B. Weaver of Iowa joined the effort. In February 1889 these men pushed through an amendment to the Indian Appropriations Bill. Offered by Rep. William Springer of Illinois, the Springer Amendment allowed Pres. Benjamin Harrison to proclaim the Unassigned Lands subject to opening.

At high noon on April 22, 1889, legal aspirants would be able to enter the Oklahoma Lands and choose 160 acres of land for an agricultural homestead. The event soon became known as the "Oklahoma Land Run" or Land Run of 1889.

See Also

CAMP RUSSELL, CHARLES C. CARPENTER, INDIAN RESPONSE TO THE BOOMER MOVEMENT, LAND OPENINGS, SETTLEMENT PATTERNS, UNASSIGNED LANDS

Learn More

Berlin B. Chapman, Federal Management and Disposition of the Lands of the Oklahoma Territory, 1866–1907 (1931; reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1979).

Stan Hoig, David L. Payne, the Oklahoma Boomer (Oklahoma City: Western Heritage Books, 1980).

Michael W. Lovegrove, "Free Homes: David L. Payne and the Oklahoma Boomer Movement, 1879–1884 " (M.A. thesis, University of Oklahoma, 1996).

Dan Peery, "Colonel Crocker and the Boomer Movement," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 13 (September 1935).

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Stan Hoig, “Boomer Movement,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=BO011.

Published January 15, 2010

© Oklahoma Historical Society