The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT.

Civil rights refers generally to rights belonging to an individual by virtue of citizenship in a country or state. In the United States, civil rights encompass the fundamental freedoms and privileges guaranteed by the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Nineteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and by subsequent acts of Congress, including the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1991. In modern parlance, the term is often associated with civil liberties and includes the right to vote, due process, and equal protection, including equal employment rights, equal education rights, and access to public accommodations. "Civil rights" is also closely intertwined with the struggles of various minority groups to attain individual and political rights. Over time, the faces of the groups involved in this quest have changed. Moreover, the intensity of the opposition that the respective groups have confronted to attain civil rights has not been uniform; some groups have suffered and endured more. As in other Southern states, however, perhaps the group whose struggles are most closely associated with the term "civil rights" are African Americans. For them, this journey has been particularly long and hard.

African Americans first came to Indian Territory as slaves of members of the Five Tribes who were forcefully moved from ancestral lands in the Southeast over the Trails of Tears and other relocations. According to the influential Black newspaper editor Roscoe Dunjee, "Following the Civil War these slaves were freed and entered into the tribal life of the Indians, intermarrying and becoming an integral part of the Red Man's life and customs." These Freedmen achieved considerable political and economic success, although issues remain as to whether the tribes were totally equitable toward them.

The next Black migrations to present Oklahoma occurred in the various land runs and lotteries of 1889 and subsequent years. Many African Americans came from the Old South, and they had experienced the pervasive discrimination reflected in Jim Crow laws. In a newly organized land soon to be a state, these Black people hoped that they would enjoy freedom at the outset. Dunjee observed that the second wave of migrating Blacks was encouraged and mobilized by the success that the Freedmen had obtained within the tribal communities. This second group was epitomized by Edward P. McCabe, a visionary and energetic Kansas businessman who helped found the town of Langston. McCabe's vision, in the words of historian Jimmie Lewis Franklin, "was a free atmosphere for progressive development, isolation from the kind of oppressive environment that characterized the 'New South,' and a healthy political setting unmarred by unwarranted restraints. Under such conditions black people could forge ahead. Oklahoma was the place—perhaps no Canaan but the next thing to it. Blacks should heed the call to 'go west.'" McCabe's influence was extraordinary, as he created a city and essentially founded the Colored Agricultural and Normal University in 1897. Later renamed Langston University, it is one of Oklahoma's first four colleges, and it is the only state-supported institution originally devoted to the education of Blacks.

However, in Oklahoma, as in most of the South after a series of narrow, restrictive decisions by the United States Supreme Court, the dominant white culture had another vision, one that actively discriminated against Black people. These white "elites" had been restricted from operation in the American Indian nations. Increased white population in Oklahoma, however, through the land runs and intermarriage with the tribes, led to the push for statehood, and the lot of African Americans dramatically declined.

In particular, the 1906 Constitutional Convention enacted a series of "race distinction" passages, including provisions segregating schools and transportation facilities. The transportation provision was deleted because of strong opposition by Pres. Theodore Roosevelt, who indicated that he would not allow Oklahoma statehood to go forward with this clause in the document. Although presidential opposition helped here and on other provisions, the new legislature readopted Jim Crow soon after statehood. Indeed, Senate Bill One, the first bill passed in the new Senate, reenacted the discriminatory transportation provision.

At the time of statehood Blacks comprised about 9 percent of the voting population. Most were loyal Republicans, supporting "the Party of Lincoln." However, Republicans soon abandoned their alliance with Blacks, running a lily-white ticket for positions on the Constitutional Convention, and then embracing Jim Crow with a fervor that equaled that of their Democratic colleagues.

The first Black to serve in the Oklahoma Legislature was Republican A. C. Hamlin, of Guthrie. His election showed that Blacks were still willing to ally themselves with the Republican Party. Democrats, dismayed at a Republican resurgence in the 1908 elections, drafted a constitutional amendment to require voters to pass a literacy test, with a "grandfather clause" that exempted most white voters. This proposal, artfully written in a very confusing ballot, disfranchised Black voters. Republicans, seeking to pick up white votes, presented only halfhearted opposition to the measure. As a result, Hamlin served only one term in the 1908 legislature. The Supreme Court would later strike down Oklahoma's grandfather clause as unconstitutional in the decision of Guinn v. United States. Nevertheless, racial manipulation of voting continued, and the Supreme Court's decision in Lane v. Wilson invalidated a state law requiring citizens who had not voted in the 1914 election to register to vote within eleven days or forfeit such right.

As racism and discrimination blossomed, two generations passed before another African American solon would sit in the Oklahoma Legislature. Historian John Hope Franklin observed that "by 1910 the Negro had been effectively disfranchised by constitutional provisions in North Carolina, Alabama, Virginia, Georgia, and Oklahoma." Systematic discrimination in restricting votes, transportation, accommodations, public schooling, college and professional training, and housing locked African Americans into positions of second-class citizenship. The nadir occurred in 1921 in the infamous Tulsa Race Massacre, in which hundreds of Blacks were killed or wounded, and the vibrant Greenwood District of Tulsa, the strongest center of Black enterprises in the state, was gutted and burned. Thirty-five square blocks of once-prosperous businesses and homes were totally destroyed. Cover-ups and a corrupt legal system conspired to provide no restitution for the tragedy.

However, as Emerson noted, "All history is biography." The emergence of a series of strong political leaders, most from the African American community, began to change the old order. Dunjee's position in this battle cannot be overemphasized. He virtually founded and funded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Oklahoma, by actively searching out test cases to advance Black civil rights, and by bringing in lawyers like Thurgood Marshall to defend Blacks unfairly charged with crimes. Dunjee's remarkable pen and consistent support of the cause with his own funds catalyzed the movement.

Ada Lois Sipuel (later Dr. Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher) volunteered to be a human experiment when she accepted Dunjee's challenge to attempt to enter the University of Oklahoma College of Law, precipitating the landmark case of Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma in 1948. After a lengthy struggle, led by Thurgood Marshall and requiring two trips to the U.S. Supreme Court, Sipuel found herself with a partial victory. The Court declared that Oklahoma had to provide her a legal education "afforded by a state institution."

The state responded by creating a one-person law school for her, with a couple of professors, and claiming the State Capitol library as the school's library resources. Sipuel went back to state court, litigating whether the "separate but equal" law school created solely for her met the Court's standards; she also continued to apply to the University of Oklahoma College of Law. Finally, university president George Cross, who had done much behind the scenes to help Sipuel, simply ordered her admitted into the law school. However, the state was grudging; she, and other students admitted to study, had to sit in special alcoves, at the back of the class, or behind ropes or chains in classes or at the cafeterias.

On June 5, 1950, while Sipuel was still in law school, the Supreme Court ended this absurd practice in McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, ruling "that the conditions under which this appellant is required to receive his education deprive him of his personal and present right to the equal protection of the laws." McClaurin was central to Chief Justice Earl Warren's efforts to break out beyond required proof of tangible discrimination to hold that separation is inherently unequal; it is arguably the precedent that made Brown inevitable. As Dr. Sipuel Fisher would later observe in her biography, "The next day [after McLaurin was announced], I moved down to the front row. I have not sat in the back ever since. McLaurin made that possible. Sipuel made something else possible. If a state could not constitutionally ship adult students out of state for schooling because of race, if it could not set up fake schools for adult students because of race, if it could not constitutionally separate adult students because of race, how could a state do any of those things to children?" The answer to Dr. Sipuel Fisher's question was but a few years away in the decision of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.

Brown, Thurgood Marshall's greatest courtroom triumph, declared separate but equal schools unconstitutional, and Democratic Gov. Raymond Gary, a white Southern Baptist, endorsed the decision, a path that few Southern governors followed. The lower federal courts sought to implement Brown's directive, but not without considerable opposition. Federal District Judge Luther Bohanon followed the Warren Court's precedents and issued comprehensive federal court orders that eventually integrated Oklahoma's schools, but he was vilified for his courageous decisions. His principal case, Dowell v. Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools (1961), traveled up and down the ladders of the courts until finally, the Supreme Court being in recess, a one-Justice decision by Justice Brennan sustained Judge Bohanon's order. As Lawrence Friedman, an authority on American legal history, observed, "The civil-rights revolution of the 1950s and the 1960s, in the historical clothing it wore, would be unthinkable without the federal courts."

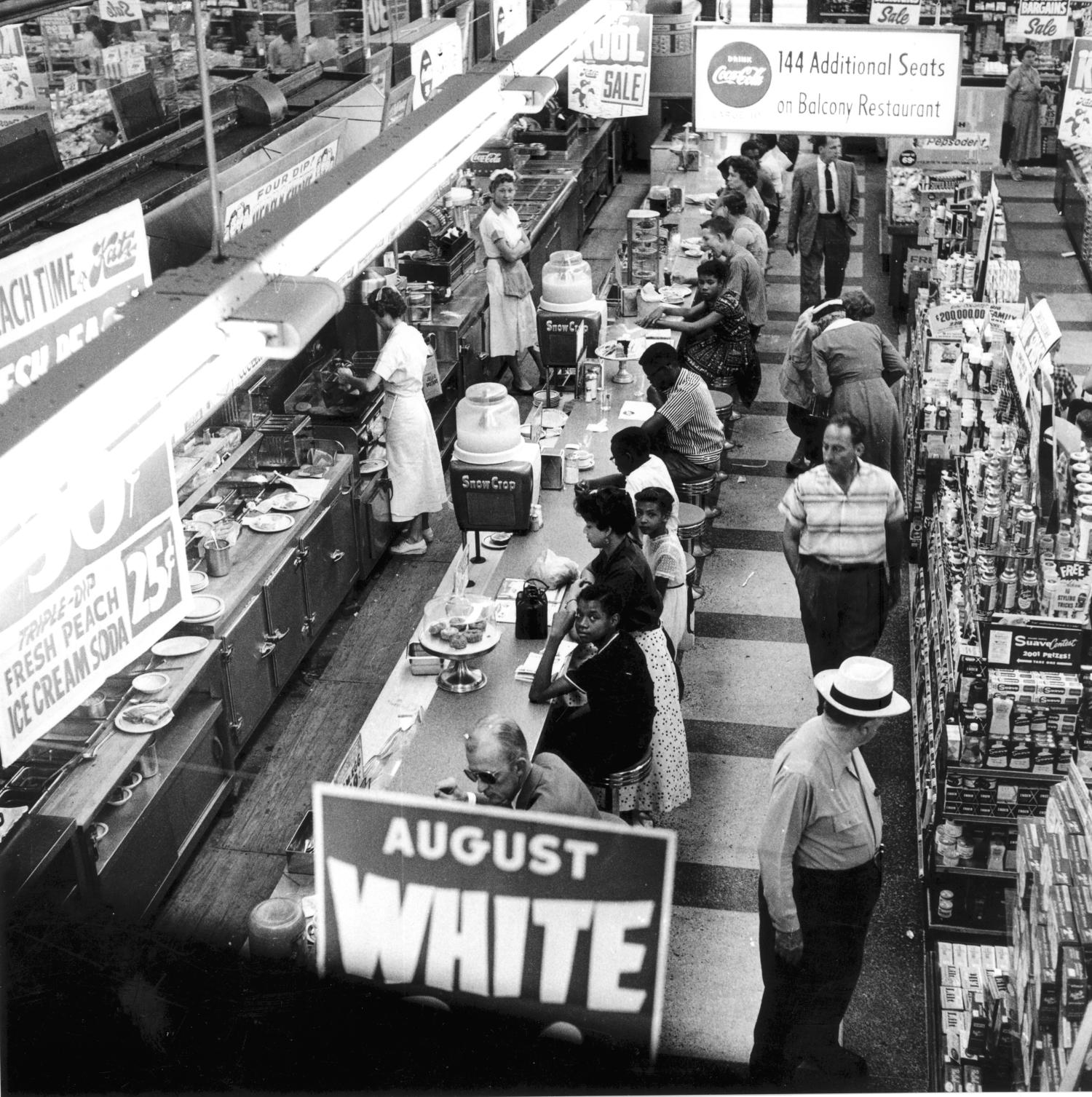

Dunjee's efforts to achieve voting power would finally pay off after the Warren Court reapportionment cases led to the drawing of fair electoral lines. John White and Archibald Hill of Oklahoma City and Curtis Lawson of Tulsa were elected to the state's House of Representatives. E. Melvin Porter of Oklahoma City became the Senate's first Black member. These solons were later joined by Rev. Ben Hill, a brilliant strategist and perhaps the most skilled orator of his day. Reverend Hill rebuilt Black political power in Tulsa. In 1969 Hannah Diggs Atkins became the first Black woman elected to the House and served there for twelve years. Described by Assistant Majority Floor Leader Hill as "head and shoulders" above many House members, Atkins shattered racist views of Black women and became one of the chambers' most influential members. She later served as secretary of state under Gov. Henry Bellmon and as a delegate to the United Nations under Pres. Jimmy Carter. Another dynamic Black woman, Clara Luper, organized sit-ins in Oklahoma that eventually ended discrimination in public restaurants. In 1994 Dr. Sipuel Fisher's victory opening the legal profession led to another key accomplishment when former state senator Vicki Miles-LaGrange became Oklahoma's first Black federal judge.

The culmination of these efforts led Dr. Sipuel Fisher, appointed by Gov. David Walters to the Board of Regents for the University of Oklahoma (which had once denied her admission), to observe in the late 1980s that although vestiges of discrimination certainly remained, Blacks had largely won the battle. In her view, African Americans should now join forces with other minorities discriminated against in Oklahoma, to help them achieve the blessings of civil rights.

Other Oklahomans have also faced civil rights challenges. Although the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention considered giving women the right to vote in 1907, that effort failed, perhaps because of racist concerns that Black women would vote in high numbers. Oklahoma granted women the right to vote in 1918, two years before states ratified the Nineteenth Amendment. However, concerns remain, such as whether women receive equal pay for equal jobs. The struggle of Oklahoma's numerous American Indians differs from that of African Americans, in terms of legal issues and complexity, although there are parallels; students of Indian civil rights should study the works of Oklahomans Angie Debo and Rennard Strickland. Congress passed the Indian Civil Rights Act in 1968 and the Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978. Other groups, including the disabled and representatives of alternative lifestyles, have appealed to all branches of government, but especially to the courts, in seeking to expand their rights in Oklahoma society.

See Also

Learn More

Bob Burke and Denyvetta Davis, Ralph Ellison: A Biography (Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Heritage Association, 2003).

Bob Burke and Angela Monson, Rosco Dunjee: Champion of Civil Rights (Edmond: University of Central Oklahoma Press, 1998).

George Lynn Cross, Blacks in White Colleges: Oklahoma's Landmark Cases (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1975).

Scott Ellsworth, Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982).

Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, with Danney Goble, A Matter of Black and White: The Autobiography of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996).

Jimmie Lewis Franklin, Journey Toward Hope: A History of Blacks in Oklahoma (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1982).

John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of American Negroes (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1947).

Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985).

Bryan A. Garner, Black's Law Dictionar y (St. Paul: West Group, 2000).

Kermit L. Hall, The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

Clara Luper, Behold the Walls (N.p.: Jim Wire, 1979).

David R. Morgan, Robert E. England, and George G. Humphreys, Oklahoma Politics and Policies: Governing the Sooner State (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991).

James R. Scales and Danney Goble, Oklahoma Politics: A History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1982).

Jace Weaver, Then to the Rock Let Me Fly: Luther Bohanon and Judicial Activism (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993).

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Robert H. Henry, “Civil Rights Movement,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=CI010.

Published January 15, 2010

Last updated July 24, 2024

© Oklahoma Historical Society