The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

TULSA RACE MASSACRE.

Believed to be the single worst incident of racial violence in American history, the bloody 1921 outbreak in Tulsa has continued to haunt Oklahomans. During the course of eighteen terrible hours on May 31 and June 1, 1921, more than one thousand homes and businesses were destroyed, while credible estimates of deaths range from fifty to three hundred. By the time the violence ended, the city had been placed under martial law, thousands of Tulsans were being held under armed guard, and the state's second-largest African American community had been burned to the ground.

One of a number of similar episodes nationwide, the outbreak occurred during an era of acute racial tensions, characterized by the birth and rapid growth of the so-called second Ku Klux Klan and by the determined efforts of African Americans to resist attacks upon their communities, particularly in the matter of lynching. Such trends were mirrored both statewide and in Tulsa.

By early 1921 Tulsa was a modern city with a population of more than one hundred thousand. Most of the city's ten thousand African American residents lived in the Greenwood District, a vibrant neighborhood that was home to two newspapers, several churches, a library branch, and scores of Black-owned businesses.

However, Tulsa was also a deeply troubled town. Crime rates were extremely high, and the city had been plagued by vigilantism, including the August 1920 lynching, by a white mob, of a white teenager accused of murder. Newspaper reports confirmed that the Tulsa police had done little to protect the lynching victim, who had been taken from his jail cell at the county courthouse.

Eight months later an incident involving Dick Rowland, an African American shoe shiner, and Sarah Page, a white elevator operator, would set the stage for tragedy. While it is still uncertain as to precisely what happened in the Drexel Building on May 30, 1921, the most common explanation is that Rowland stepped on Page's foot as he entered the elevator, causing her to scream.

The next day, however, the Tulsa Tribune, the city's afternoon daily newspaper, reported that Rowland, who had been picked up by police, had attempted to rape Page. Moreover, according to eyewitnesses, the Tribune also published a now-lost editorial about the incident, titled "To Lynch Negro Tonight." By early evening there was, once again, lynch talk on the streets of Tulsa.

Talk soon turned to action. By 7:30 p.m. hundreds of whites had gathered outside the Tulsa County Courthouse, demanding that the authorities hand over Dick Rowland, but the sheriff refused. At about 9 p.m., after reports of the dire conditions downtown reached Greenwood, a group of approximately twenty-five armed African American men, many of them World War I veterans, went down to the courthouse and offered their services to the authorities to help protect Rowland. The sheriff, however, turned them down, and the men returned to Greenwood. Stunned, and then enraged, members of the white mob then tried to break into the National Guard armory but were turned away by a handful of local guardsmen. At about 10 p.m. a false rumor hit Greenwood that whites were storming the courthouse. This time, a second contingent of African American men, perhaps seventy-five in number, went back to the courthouse and offered their services to the authorities. Once again, they were turned down. As they were leaving, a white man tried to disarm a Black veteran, and a shot was fired. The riot began.

Over the next six hours Tulsa was plunged into chaos as angry whites, frustrated over the failed lynching, began to vent their rage at African Americans in general. Furious fighting erupted along the Frisco railroad tracks, where Black defenders were able to hold off members of the white mob. An unarmed African American man was murdered inside a downtown movie theater, while carloads of armed whites began making "drive-by" shootings in Black residential neighborhoods. By midnight fires had been set along the edge of the African American commercial district. In some of the city's all-night cafes, whites began to organize for a dawn invasion of Greenwood.

During the early hours of the conflict local authorities did little to stem the growing crisis. Indeed, shortly after the outbreak of gunfire at the courthouse, Tulsa police officers deputized former members of the lynch mob and, according to an eyewitness, instructed them to "get a gun and get a nigger." Local units of the National Guard were mobilized, but they spent most of the night protecting a white neighborhood from a feared, but nonexistent, Black counterattack.

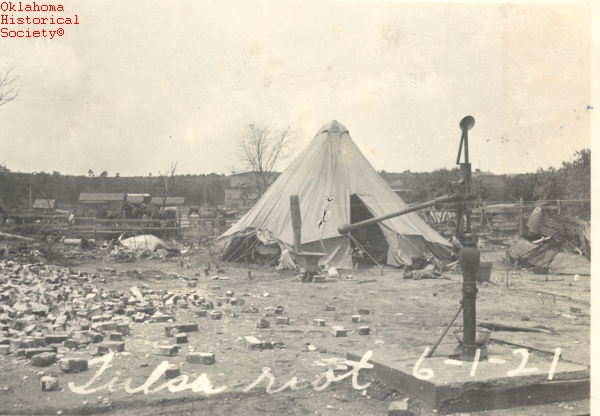

Shortly before dawn on June 1, thousands of armed whites had gathered along the fringes of Greenwood. When daybreak came, they poured into the African American district, looting homes and businesses and setting them on fire. Numerous atrocities occurred, including the murder of A. C. Jackson, a renowned Black surgeon, who was shot after he surrendered to a group of whites. At least one machine gun was utilized by the invading whites, and some participants have claimed that airplanes were also used in the attack.

Black Tulsans fought hard to protect their homes and businesses, with particularly sharp fighting occurring off of Standpipe Hill. In the end, they were simply outgunned and outnumbered. By the time that additional National Guard troops arrived in Tulsa at approximately 9:15 a.m. on the morning of June 1, most of Greenwood had already been put to the torch.

A brief period of martial law was followed by recriminations and legal maneuvering. Even though Dick Rowland was exonerated, an all-white grand jury blamed Black Tulsans for the lawlessness. Despite overwhelming evidence, no whites were ever sent to prison for the murders and arson that occurred.

The vast majority of Tulsa's African American population had been made homeless by the event. Yet, despite efforts by the white establishment to force the relocation of the Black community, within days of the violence Black Tulsans had already begun the long and arduous process of rebuilding Greenwood. Thousands, however, were forced to spend the winter of 1921–22 living in tents.

The deep scars left by the tragedy remained visible for years. While Greenwood was eventually rebuilt, many families never truly recovered from the disaster. Moreover, for many years the violence became something of a taboo subject, particularly in Tulsa. A state commission was formed in 1997 to investigate. The report recommended that reparations be paid to the remaining Black survivors. A team of scientists and historians uncovered evidence supporting long-held beliefs that unidentified victims had been buried in unmarked grave sites.

One of the great tragedies of Oklahoma history, this eruption of bloodshed and destruction in Tulsa has lived on as a potent symbol of the ongoing struggle of Black and white Oklahomans to forge a common destiny out of an often troubled past.

See Also

AFRICAN AMERICANS, CHARLES FRANKLIN BARRETT, GREENWOOD DISTRICT, KU KLUX KLAN, LYNCHING, NEWSPAPERS–AFRICAN AMERICAN, OKLAHOMA NATIONAL GUARD, JAMES BROOKS AYERS ROBERTSON, SEGREGATION, ANDREW J. SMITHERMAN, TULSA, TULSA TRIBUNE, TWENTIETH-CENTURY OKLAHOMA

Learn More

Scott Ellsworth, Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982).

John Hope Franklin and Scott Ellsworth, eds., The Tulsa Race Riot: A Scientific, Historical and Legal Analysis (Oklahoma City: Tulsa Race Riot Commission, 2000).

Eddie Faye Gates, They Came Searching: How Blacks Sought the Promised Land in Tulsa (Austin, Tex.: Eakin Press, 1997).

Loren L. Gill, "The Tulsa Race Riot" (M.A. thesis, University of Tulsa, 1946).

Robert N. Hower, "Angels of Mercy": The American Red Cross and the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot (Tulsa, Okla.: Homestead Press, 1993).

Mary E. Jones Parrish, Events of the Tulsa Disaster (Tulsa, Okla.: Out on a Limb Publishing, 1998).

Related Resources

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Scott Ellsworth, “Tulsa Race Massacre,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=TU013.

Published January 15, 2010

Last updated July 29, 2024

© Oklahoma Historical Society