Tenant Farming in Oklahoma

Printable Version

Agriculture has played a central role in the growth and development of Oklahoma, fundamentally shaping the state’s economic and cultural identity. Until the mid-20th century, more than half of the state’s inhabitants lived on farms, raising a wide variety of crops and livestock. Some owned their farms, while others rented the land in exchange for a portion of their crop or a fee. These renters were called tenants, and, from 1910 to 1940, they made up the majority of Oklahoma’s farmers.

In addition to Oklahoma’s strong agricultural tradition, the state also has a long history of labor advocacy. Labor advocacy takes many forms, but it usually involves a group of people from the same job or industry working together to improve their collective situation through activism or protest. Farmers recognized that they, too, could organize to advocate for their needs and potentially bring about positive changes for themselves and their communities. These various farmer advocacy groups had many names and goals, with the union structure becoming particularly popular in the early 20th century.

Teenage children of Oklahoma tenant family helping out on their farm (image courtesy the Library of Congress).

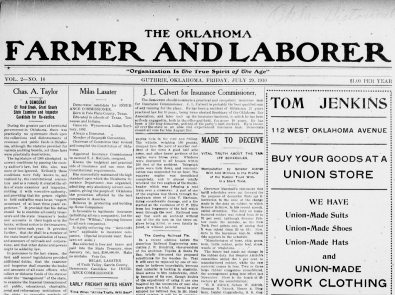

The Oklahoma Farmer and Laborer, a weekly newspaper covering agricultural and union news, 1910.

Unions had existed in the United States for decades, mostly among industrial workers. They tended to be fairly organized and operated on a membership basis, with members paying dues to support union activities. Farmer unions differed from industrial unions in that they lacked a clear hierarchy to fight against, and their demands tended to be broader. While a union of miners could go directly to their boss and ask for better wages, farmers had to contend with shifting crop prices, expensive processing and transportation costs, and even competition from other farmers—issues which have many causes and few clear solutions. Still, farmers unions emerged across the country. In Oklahoma, with the state’s strong agricultural base and labor reform history, unions had a favorable environment for farm labor activism.

Though there were organizations that spoke to the general experience and struggles of all farmers, many Oklahoma unions focused on helping tenants. As these organizations looked beyond the day-to-day struggles of the farmer and began to question the fundamental power relations at play in a tenant system, they became increasingly radical. This radicalism and the backlash it aroused, along with the decline in tenancy that occurred during the 1930s and 1940s, effectively killed these tenant-focused organizations, while the less radical, more general unions survived.

The history of Oklahoma’s farm unions demonstrates the power and potential of community activism to enact change. Though these organizations had various levels of success in achieving their goals, they were all initially inspired by a shared desire for individual and community betterment. Many people today can empathize with that desire and, hopefully, learn from the past to change the future.

Members of the Muskogee chapter of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union attending a meeting (image courtesy of the Library of Congress).