Tenant Farming in Oklahoma

The Shawnee Demands

In 1906, as the Twin Territories prepared to become one state, different interest groups met to prepare for the Constitutional Convention. Different groups had their own goals for what the Constitution of the State of Oklahoma would eventually look like, and this included the unions such as the Farmer’s Union. The Twin Territories Federation of Labor, the Oklahoma Farmer’s Union, and several groups of railroad workers met in August to discuss what they wanted in the Constitution and how they should make sure their views were included. At this meeting, which took place in Shawnee, these groups agreed on the “24 Demands” or, as they are now known, “The Shawnee Demands.”

Many newspapers published the demands in full for their readers to review, such as this issue of The Edmond Sun, September 19, 1906. Read this article on The Gateway to Oklahoma History.

These groups supported goals that benefitted labor, farmers, and the general public, such as the demand for free textbooks and mandatory education. Populists desire for election reform appeared in the demands for the initiative, referendum, recall, and a primary for statewide elected offices. They opposed banning the state from any engaging in any kind of industry. They supported early worker’s compensation reform by allowing compensation if a worker was injured by another worker’s error; in most states, courts found that the employer was not at fault in those cases. These groups supported an eight-hour workday for several different industries. The Shawnee Demands included sought significant regulation and oversight by the government in the economy and people’s lives, including electing commissioners of labor and agriculture, a mine inspector, a corporation commission, and a tax commission. All of these regulators would have the power to compel corporations and owners to comply with their demands. They supported health inspections of homes and businesses.

The authors of the Shawnee Demands also opposed several policies. They wanted to ban child and convict labor, with the exception of allowing prisoners to work on road maintenance. They wanted to ensure that employees could make their own political and economic decisions, free from the interference of their employers. They opposed speculation in farm products and wanted the practice to end. They also supported a range of limits on corporate behavior, from banning railroads from owning mines to requiring corporations to acquire a charter before they could do business in the state.

Once these demands were arrived at, local newspapers debated the points through articles, announcements of candidacy, and letters to the editor. The decision of these organizations to create a platform with their preferences for the constitution before delegates were elected meant supporters of the demands could assess each candidate according to how warmly they supported the list.

These demands were shared with potential delegates to the Constitutional Convention, and most Democrats often proudly campaigned on their support of them in their effort to be elected to the Convention. A total of 70 delegates—67 Democrats and three Republicans—that had committed to the Shawnee Demands were elected out of 112 seats. The vast majority of the Shawnee Demands were incorporated into the Oklahoma Constitution, a major achievement for both the Farmer’s Union and the labor unions. The result of farmer and labor advocacy was the most progressive state constitution written up to that time.

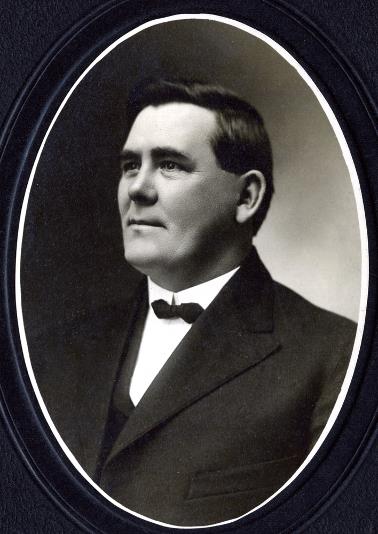

Peter Hanraty, union leader and delegate to the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention, helped write the Shawnee Demands (4566, Frederick S. Barde Collection, OHS).