Tenant Farming in Oklahoma

Tenant Unions

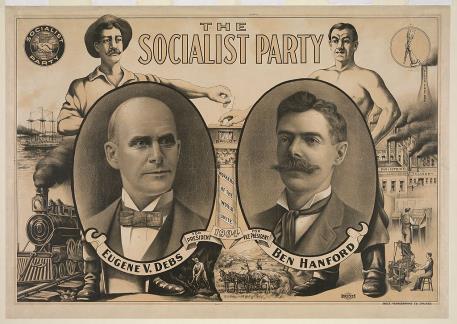

Alongside general unions such as the Farmers’ Union, there were a number of unions that expressly and solely advocated for the tenant farmer. These groups began to question the power relations of tenancy and propose increasingly more radical measures. They were often inspired by or directly associated with the Socialist Party, which had started to grow in popularity in Oklahoma and the United States as a whole.

Socialist Party poster for the election of 1904 (image courtesy of the Library of Congress).

Oklahoma Renter’s Union

The Oklahoma Renters’ Union, founded in 1909, was one such group. They evolved directly from the Oklahoma Socialist Party and had high hopes of ending land competition between tenants, abolishing landlordism, providing tenants with better housing and education, and, eventually, creation of a program where tenants could rent and buy state land at reduced rates. Recruitment proved difficult, however, due to discrimination by landlords, with many refusing to rent land to tenants who were members of the organization. Additionally, the group would not allow African American or American Indian tenants to join, limiting their support base. These external and self-inflicted challenges made the organization largely ineffective, and the Renters’ Union soon faded into obscurity.

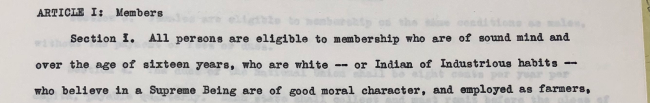

The Renters’ Union was not the only group to restrict membership based on race. Many labor organizations refused to admit African American farmers, despite sharing similar struggles and desires for change. Some groups did allow American Indian farmers to join, but this often came with more subtle forms of prejudice, as can be seen in a Farmers’ Union constitution specifying that American Indian members must be of “industrious habits.” Later activists, most notably the founders of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, realized that class united the farmers more than race divided them and welcomed diversity in their organizations. Still, it’s notable that even amongst those who were economically progressive for their time, racism was still prevalent.

Excerpt from an Oklahoma Farmers’ Union constitution outlining membership requirements (1981.105. Federal Writers’ Project Collection, OHS).

Working Class Union and the Green Corn Rebellion

While some organizations mainly engaged in the theoretical, others focused on actions over ideals, such as the subversive and ultimately explosive Working Class Union (WCU). Founded in 1913, the WCU rejected the doctrine of nonviolence embraced by similar groups. The WCU was formed after the Industrial Workers of the World, a prominent national labor union, refused to admit tenant farmers. The platform of the new union differed little from similar organizations of the time, advocating for the end of tenancy and various improvements to working conditions. Still, the WCU is distinguished by its use of violence and conspiracy to achieve its aims. Members would harass landlords and even rob banks, in addition to more conventional political action.

The unconventional advocacy of the Working Class Union would reach its peak with the Green Corn Rebellion of 1917, an armed revolt protesting the draft for World War I. Aside from arguments about personal liberty and opposition to the war itself, tenant farmers also feared the loss of a significant portion of their labor force. With crop prices increasing rapidly due to wartime demand, farmers needed their young men more than ever. However, no exemptions came, and thousands of men were called to fight.

Young man resting after working in the fields on his family’s farm (image courtesy of the Library of Congress).

Sheet music cover of a patriotic song by Andrew B. Sterling and Arthur Lange (image courtesy Wikimedia Commons).

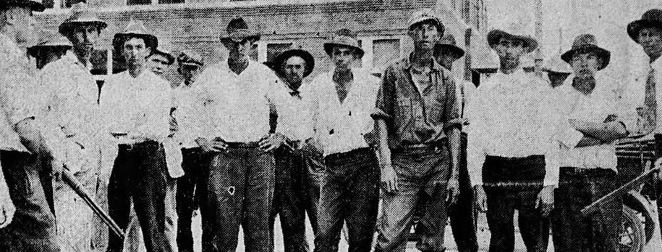

Fight they did, though not against the Central Powers. Instead, on August 2, 1917, hundreds of men gathered at a farm in central Oklahoma with a plan to march from Oklahoma to Washington, DC, where they would demand an end to the war, surviving on green corn along the way. Obviously, this was impossible, and they instead began destroying public property before being met by a local militia. The ensuing conflict left three protestors dead and many others arrested. This event, though highly localized and minimally destructive, caused a great media frenzy and resulted in the collapse of the Socialist Party in Oklahoma, and the Working Class Union itself. This event reveals the deep discontent and instability felt by the state’s tenants, and the power of collective organizing to mobilize a large group towards a common, if misguided, goal.

Participants in the Green Corn Rebellion of 1917 (image courtesy of the California Digital Newspaper Collection).