African Americans in Oklahoma Before 1954

Printable Version

The state of Oklahoma has a unique history. That is also true of the African Americans who settled here and their descendants. For those enslaved by tribal members, the Civil War resulted in the granting of land and, to a certain extent, status within the Five Tribes. This core set of landed Blacks drew freedmen from the South and idealistic African Americans from across the US who wanted to create a space protected from the raw racism and barriers to economic opportunity that existed in the rest of the country. The ease of securing land in Indian Territory in the late 1800s proved beneficial for the small African American communities popping up throughout both Indian and Oklahoma Territories. Access to the traditional form of wealth—land—sparked vibrant economies. Black communities with money attracted more entrepreneurs, skilled laborers, and professionals. The territorial period in Oklahoma offered opportunity for African Americans unmatched anywhere else in the country.

With statehood came a major shift in the daily experience for African Americans. The state rapidly established the most comprehensive system of segregation in the US. To put this system in place, whites used multiple forms of violence: forcing Black residents to move, lynching, and massacre are all events in Oklahoma’s history. In between the state laws and the extralegal violence, there also emerged organized white groups—from neighbors who agreed to only sell to whites, to the KKK—that cooperated to deny Black Oklahomans their rights and economic opportunity.

As in the rest of the nation, Black Oklahomans resisted these changes. Because of the diversity of the Black population, its relative wealth, and the powerful organizations that existed in Black communities, the efforts of Black Oklahomans to create systems of equality laid the groundwork for the national Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

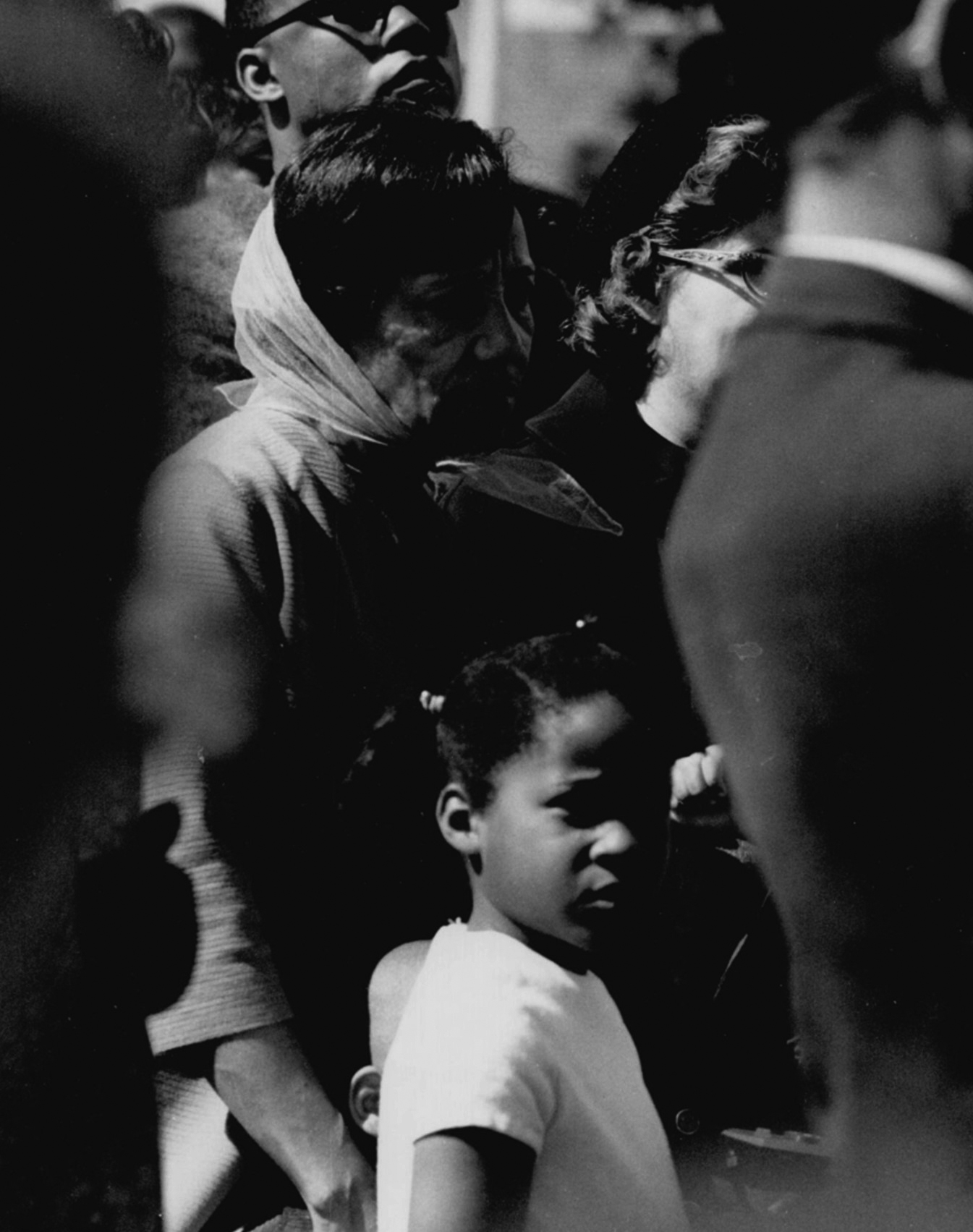

This family attending a 1968 demonstration was part of the Civil Rights Movement in Oklahoma, which took place over decades 2012.201.B0927.0743, OPUBCO Collection, OHS).

Freedmen

Permanent Black settlement in Oklahoma dates back to the 1830s, although some Blacks came with early European explorers many years prior to the formation of Indian Territory. Between 1830 and 1842, the federal government forcibly removed the Five Tribes from their land in the southeastern portion of the United States and relocated them to Indian Territory. Because each of these tribes had adopted the institution of slavery from earlier contact with the British and Americans, many within the tribes held Black people in enslavement. These journeys known as the Trail of Tears, introduced permanent Black settlement in Indian Territory.

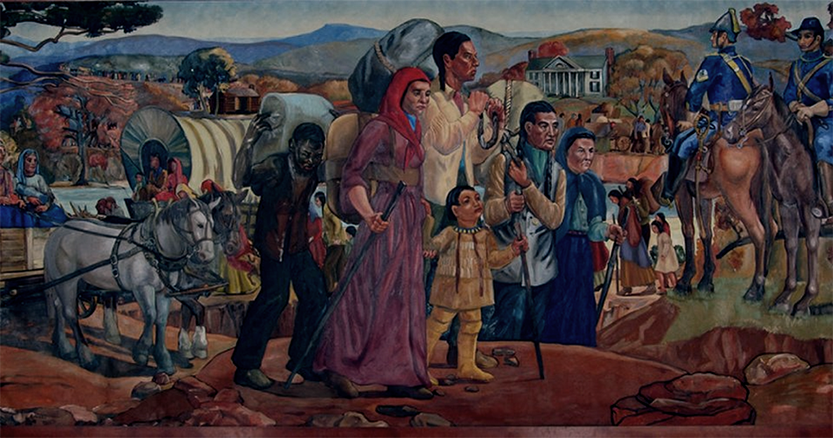

Trail of Tears by Elizabeth Jane shows enslaved people on the forced march to Indian Territory (OHS).

After the Civil War, the Reconstruction Treaties of 1866 included provisions for emancipation, access to land, and recognition of rights within the respective Native nation. Many Freedmen chose to live near each other.

In the late 1800s, a movement to force the adoption of private land ownership became popular. The government introduced the Dawes Severalty Act (1887) and the Curtis Act (1898), which provided for the allotment of a piece of tribal land to each of its citizens. This included the Freedmen. Similar to the period after emancipation, Blacks often selected plots near each other.

Much like other members of these tribal nations who were allotted land, many Freedmen were vulnerable to efforts by non-tribal members wanting to gain control of their allotment. This was especially true if a valuable resource such as oil was discovered on the allotment, or if railroads or land developers desired the land. In the early stages of allotment, landowners were not allowed to sell their land. A typical strategy to gain control of land owned by Freedmen was for an outside party to argue the landowners were incompetent and unable to control their affairs. The allottee would be taken to court and a guardian, usually white, would be appointed to make the financial decisions for their ward. Sometimes these individuals made decisions to benefit their wards. Other guardians charged large fees to their wards and sometimes drained their accounts. The population of Blacks in the Twin Territories increased as the land left over after allotment was offered to non-Indian settlement. The various means of distributing land, such as land runs and lotteries, attracted a number of Black settlers.

Sarah Rector

Sarah Rector was an African American member of the Muscogee Nation. She was born in 1902 near the historic All-Black town of Taft. Because she was a tribal member, she received an allotment of land. She owned this land, but her dad managed it because she was still a child. In order to pay taxes on the land the family owned, he leased Sarah’s land to an oil company. On October 24, 1913, oil was discovered on Sarah Rector’s allotment. More than 200 barrels gushed from her land every hour. Her income soon rocketed to $1,100 a month. In 1915, $1,100 had the same purchasing power as $28,000 does today! She quickly became a millionaire. Control over the land was taken from Rector’s parents, and guardianship was granted to a white man named T. J. Porter. Sarah Rector used her wealth to make other investments, but by her death in 1967, a large portion of her wealth was gone.

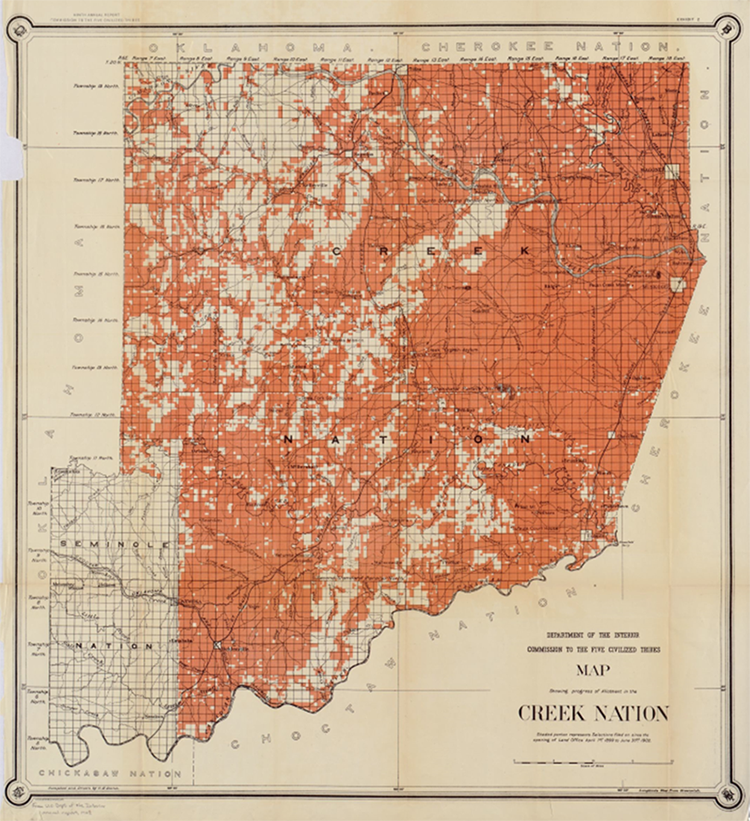

Allotments in the Muscogee Nation, 1902 (image courtesy Library of Congress).

Drovers

In addition to the Freedmen, there were significant populations of African Americans within the borders of Indian Territory throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century. The incredible growth of the cattle industry as urban populations in the East demanded meat introduced the continual presence of Black drovers, who escorted cattle to the railheads in Kansas from Texas. Numbers vary, but a significant portion of the workforce moving cattle through Indian Territory were Black.

Many Black cowboys had been formerly enslaved and responsible for caring for livestock or working in a kitchen. For many of these workers, the challenges of the long drive were small compared to the lack of opportunity offered by sharecropping, the kind of work most African Americans did. Drovers’ pay often seemed too low to potential workers, but for Black cowboys, the pay was better than most of the other employment available, especially if one worked as a trail cook, a job often held by a Black worker.

Some Black cowboys appreciated the relative lack of discrimination during most of the drive. Traveling through the sparsely populated Indian Territory, the group of 12 to 15 men and boys usually had few interactions with strangers. Black cowboys faced strict segregation and other racist laws and customs only in the parts of towns where white women lived.

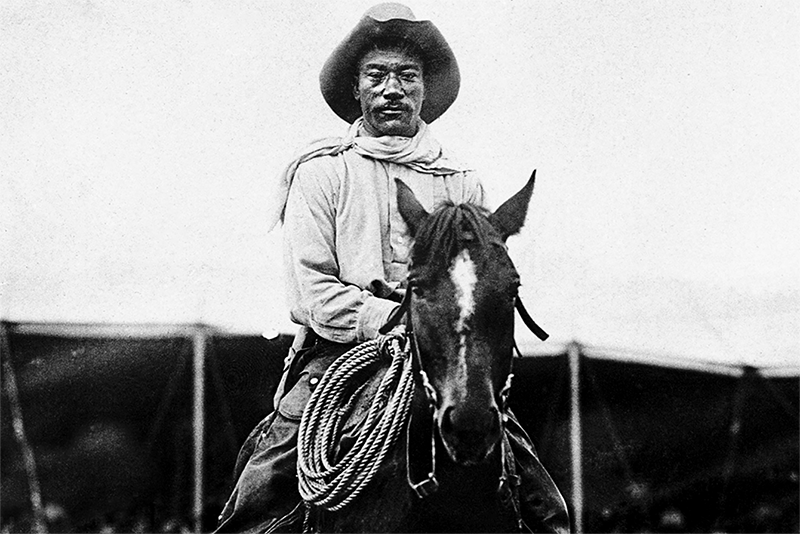

Bill Pickett is Oklahoma’s most well known Black cowboy (image courtesy Texas Highways Magazine).

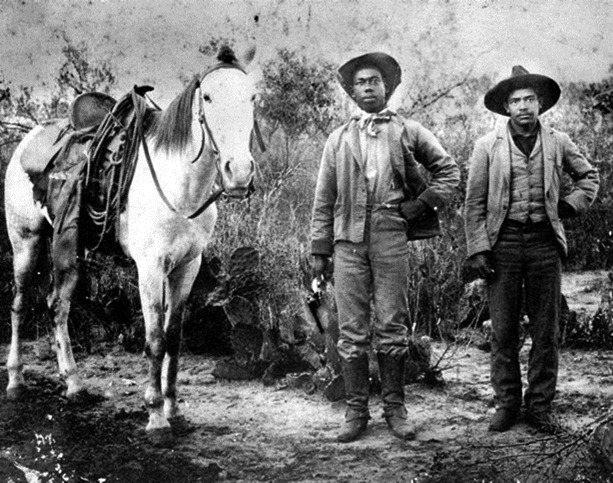

Cowboys, c. 1900 (image courtesy UTSA Libraries Special Collections).

Buffalo Soldiers

From 1866 until the allotment period, Buffalo Soldiers were frequently stationed at forts in Indian Territory. They were given a number of responsibilities: maintaining peace among the tribal nations and escorting supply wagons and rail and telegraph workers. They also engaged in numerous conflicts, large and small, with the Plains tribes recently forced to reservations in Indian Territory. From 1881, the responsibilities of soldiers in Indian Territory included the expulsion of Boomers seeking to force the opening of land to non-Indian settlement. This became a primary activity for Buffalo Soldiers as the decade of the 1880s unfolded.

Much like the cattle drives, the army offered some Black men the opportunity to earn a better wage and avoid the system of segregation rapidly spreading across the South and West. During the latter half of the nineteenth century, Buffalo Soldiers fought against different tribal nations during the Plains Wars. Many units of Black soldiers were especially respected by their foes for their ability to stay cool in an intense battle, their horsemanship, and their coordinated tactics. A total of 19 Black men and two infantry units earned the Medal of Honor between 1866 and the early 1890s.

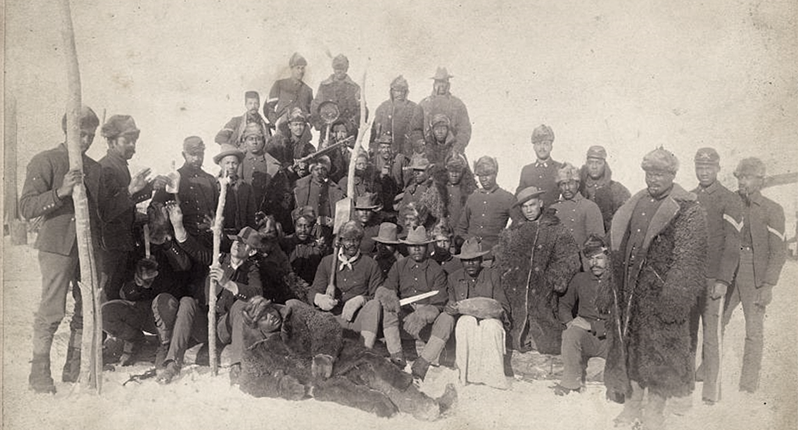

Buffalo Soldiers were highly respected for their skill and bravery by many of their American Indian opponents during the Plains Wars. Their opponents gave the soldiers the name “Buffalo Soldier” because the soldiers’ hair reminded them of bison hides (image courtesy Library of Congress).

All-Black Towns

As non-Indian settlement descended on Indian Territory, many Freedmen and settlers established All-Black towns to protect themselves and make life more enjoyable. After the Civil War, the US government forced the Five Tribes to provide lands and rights to Freedmen within their own nations. When the tribes’ communally-held land was divided into individual allotments in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Freedmen were allotted land. Many Freedmen selected plots near each other, and some of these locations grew into All-Black towns in Indian Territory. In Oklahoma Territory, many Blacks settled near each other after the land runs.

In both Oklahoma and Indian Territories, All-Black towns provided safety, community, and opportunity for their residents. Boley, located in Okfuskee County, was founded in 1903. In a short time, thousands settled in or near this vibrant city, which included two banks, two colleges, electricity, and an ice plant. Langston, well known because it is the location of the historically Black college or university (HBCU) of the same name, was founded by Edward P. McCabe in 1890. Originally named Lincoln and founded in 1903, Clearview is located in Okfuskee County. At its peak, the town had a newspaper, a brick school building, two churches, and an excellent baseball team. Taft was the site of several schools, a mental hospital, and correctional centers.

Today, there are 13 historically All-Black towns still in existence.

This map shows Oklahoma’s All-Black towns (OHS).

Clearview residents pose for a photograph (20699.02.197.329, Currie Ballard Collection, OHS).