African Americans in Oklahoma Before 1954

Segregation in Oklahoma

Segregation means “to separate.” In the southern US in the 1880s and 1890s, many counties and states passed laws that separated whites from Black people. The purpose of these laws was to make whites feel like they were a part of a special group and better than Blacks. In 1896, the United States Supreme Court declared that these governments could segregate people in a case called Plessy v. Ferguson. This court case established a precedent, which said that the government could segregate if the things offered to both groups were “equal.” African Americans and some whites protested this decision. Many believed that just the separation made Blacks and whites unequal.

The Five Tribes were relocated from the region that would become known as the South, and these nations adopted many of the values and cultural practices that non-Indians brought to the region. This included the enslavement of Blacks. Later, in the 1800s, many who moved to Oklahoma as it was

Jim Crow During the Territorial Period

As Oklahoma Territory became organized and governed by non-Indians, it lacked laws requiring segregation, or Jim Crow laws. The first Territorial Legislature allowed counties the option to have segregated or integrated schools. During the territorial period, the idea of segregated schools became more popular, and in 1897 the Territorial Legislature passed a law requiring segregation in schools.

The Wilson family moved to Guthrie along with thousands of others as part of the Land Run of 1889. Even though the school year was only a month long, this Black family’s two children, Eva and Janetta, attended the only school and their classroom was integrated. The following year, the Black children in the neighborhood continued to attend an integrated school. In the spring of 1891, Logan County residents voted to segregate. The next school year, Belle Wilson, the mother of the children, attempted to enroll her children in school and was refused by the teacher. The new school for African American children was significantly farther than the four blocks the children walked to their original school. For a month, parents continued to try to enroll the children at their original school and appealed to county officials for assistance. The family sued the school district. This case gained the attention of the territorial attorney general, who took over the case. The case went back and forth as it moved through the court system. The Wilson family would lose their case, as would later Black Oklahomans before the Supreme Court found the principle of “separate but equal” unconstitutional in 1954.

Plessy v. Ferguson produced a wave of segregation laws and ordinances that affected the lives of Blacks and whites (image courtesy Birmingham Public Library).

The Oklahoma State Constitution

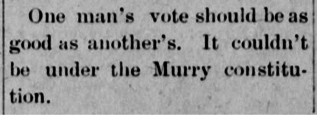

The Enabling Act (1906) allowed people in the Twin Territories to prepare for statehood, and the election of delegates to a constitutional convention took place. William H. Murray, president of the constitutional convention, held racist beliefs. He stated in the first speech at the convention that Blacks could never be equal to whites. He worked to include strict segregation and voting restrictions in the state constitution, as did many of the other delegates. These Oklahomans wanted the state constitution to prevent marriage between whites and Blacks, and to segregate schools and public facilities. They also wanted to include a section that would take away Black Oklahomans’ right to vote. The segregation and voting restrictions in the state’s founding document was one of the most hotly debated issues to come out of the convention.

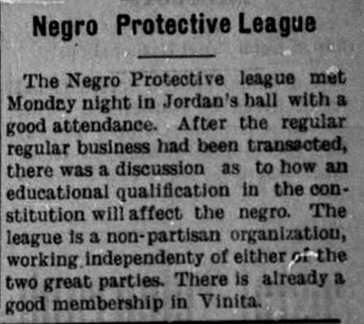

Many African Americans were angry at this attempt, and they organized to advocate for themselves. They formed the Negro Protective League. This civil rights organization had chapters throughout the state with hundreds of members. They held mass meetings and mailed thousands of letters to convince people that the constitution, as written, should be opposed. They passed a series of resolutions concerning what the constitution should include and shared these with delegates and newspapers. A group of African American leaders from the Negro Protective League in Oklahoma traveled to ask the president in person to oppose the constitution. Theodore Roosevelt did not do as they asked, but the leaders in Oklahoma were fearful that the president would not support the constitution if it included major sections commanding segregation. They decided to keep only the section requiring school segregation in the constitution.

The Vinita Daily Chieftain, September 5, 1906

Front page of The Muskogee Cimeter, June 21, 1907. The Muskogee Cimeter was an important African American newspaper in early Oklahoma.

Senate Bill One

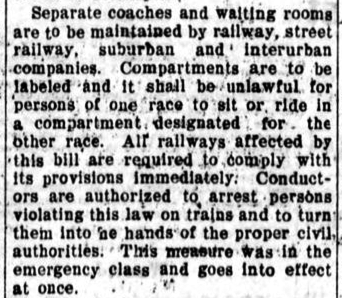

Because segregation and voting restrictions became such a central part of the debate around the constitution, many people in Oklahoma wanted to make sure the first legislature passed Jim Crow laws rapidly. Four days into the first state legislative session, the Oklahoma State Senate passed the first state law, Senate Bill One, as emergency legislation. Known as the “Separate Coach Bill,” this law required public transportation to be segregated. It passed the senate with a vote of 37 to 2, while it passed the house 91 to 14. Governor Charles Haskell signed the bill into law.

The African American community in Oklahoma responded with anger at this introduction of segregation into new areas. In Red Bird, they threw rocks and coal at a train carrying state officers and Democratic politicians to a convention. In Taft, Black residents burned the depot down. Many Black Oklahomans simply refused to comply with the law early in its enforcement. After the initial response, the Negro Protective League took to the courts in an effort to defend their rights and repeal this law. Langston founder and Republican Party leader E. P. McCabe filed suit, as did The Muskogee Cimeter editor and lawyer W. H. Twine. The McCabe case made it to the Supreme Court; the justices found the segregation law constitutional.

A summary of the requirements of Senate Bill One from The Walters Journal, December 26, 1907.

Legislators and their families gather to celebrate passing Oklahoma’s Jim Crow law, the first law passed by the state (1104, Oklahoma Historical Society Photograph Collection, OHS).

The “Separate Coach Law,” as Senate Bill One was also known, led to other segregation laws and ordinances (image courtesy Library of Congress).