Commerce in Oklahoma

Trade and the Columbian Exchange

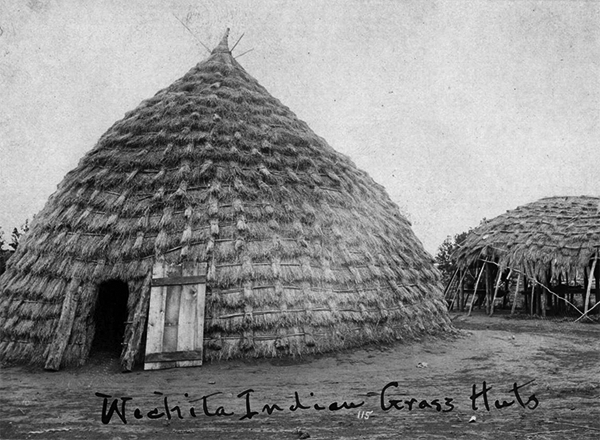

Long before European explorers made their way to present-day Oklahoma, various tribal nations traded, both long-distance and locally. The nomadic tribes such as the Plains Apache and Kiowa, who frequented the territory that became western Oklahoma, were not as active in trading as the settled, nonmigratory tribes of the southeast, such as the Caddo and Wichita. Long-distance trade routes shifted over time, while local trade was more consistent throughout the centuries. A wide variety of goods were traded all over the continent, including hides, cotton cloth, copper, unique feathers, and shell beads. Having been established before European contact, these trade routes and connections laid the groundwork for future trade across the continent. Each nation was a distinct community with different ideas, religions, and languages. Once Europeans began settling in the western hemisphere, the nations developed very different strategies for interacting with Europeans and other tribes. The tribes faced the difficult task of maintaining their ideals, cultures, and means of survival while countering European explorers and traders trying to acquire land, gain commercial opportunities, and assimilate Native people.

She-de-ah, Wild Sage, A Wichita Woman, by George Catlin, 1864 (image courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum).

The arrival of European explorers to the western hemisphere provided many European countries with new opportunities for economic advancement. Silver, new crops, rumors of magical golden cities, and a chance to expand their own holdings drove the leaders of these countries to send large groups of explorers to the continent. The Columbian Exchange began shortly after, and eventually reached North America and the tribal nations of present-day Oklahoma. This exchange brought new foods, like corn, beans, potatoes, and tobacco to the Europeans, as well as new mineral wealth, furs, and new Christian converts. The Columbian Exchange introduced decorative materials, coffee, tea, and sugar, and new technology. Horses, steel, and guns were among the technological innovations the tribes gained access to through trade. Technology enticed tribes to establish trading relationships with groups of Europeans, and propelled commerce into new eras of growth and potential, such as fostering better transportation or developing new tools.

A Wichita dwelling (4145, E. N. Yates Collection, OHS).

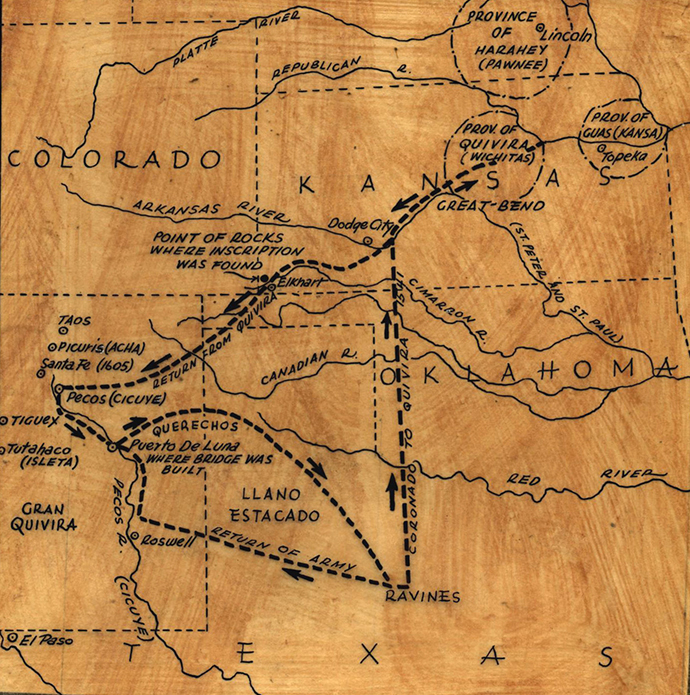

Spanish exploration into North America began with the failed mission of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado in 1540. He, accompanied by a large crew of slaves, soldiers, horses, and cattle, searched for the mythological cities of gold. A portion of his crew broke off and traveled the path eventually known as the Santa Fe Trail, a trade route that extends from Franklin, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, with a branch passing through Oklahoma. The Spanish were persistent in their search for the cities of gold, and many of their travels through the area led to conflict with the French and the American Indians, often over their claims to the land.

The Columbian Exchange also brought terror and disease. American Indians were exposed to infectious diseases like smallpox, malaria, and the bubonic plague. These diseases profoundly damaged the Indigenous population, which had no immunity, reducing the Western hemisphere’s population. Europeans, especially the Spanish, forced the tribes to convert to Christianity. The English dispossessed tribal nations of land, sometimes through violent conflict or trickery. The fur trade with the French resulted in overhunting of wildlife. While the introduction of new technology and trade opportunities was positive in many ways, the Columbian Exchange also brought damage and oppression with it.

Coronado explored the interior of the North America (2012.201.B0144.0287, OPUBCO Collection, OHS).

A possible route of traveled by Coronado in 1541 ( 2012.201.B0144.284, OPUBCO Collection, OHS).

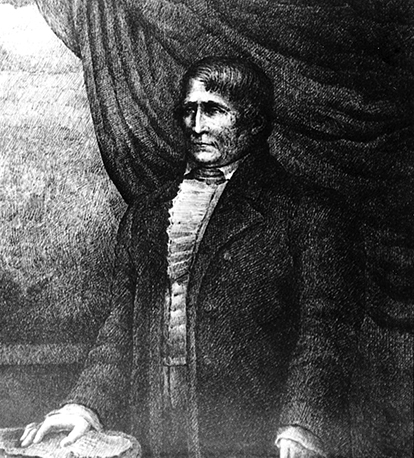

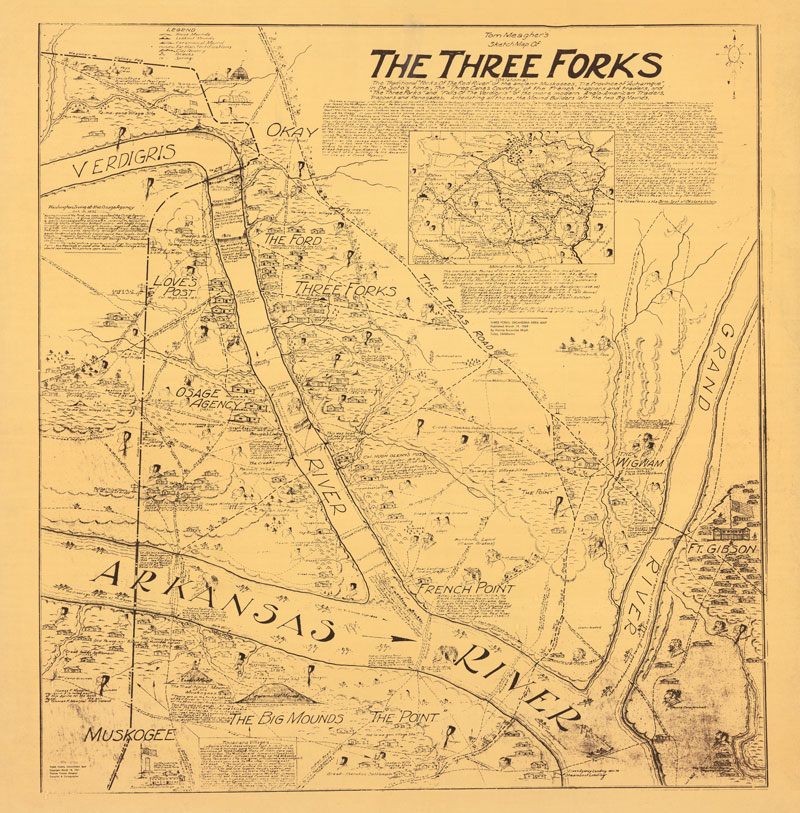

Both the French and Spanish made their mark on the area that became Oklahoma. French fur traders took great advantage of rivers and stretched their business from Quebec to the Rio Grande. The French began trading in Oklahoma by 1719 and worked alongside American Indians to establish a strong fur trade in the area. Many trading posts were established along rivers, specifically in the Three Forks Region. Commerce, rather than land acquisition or empire, motivated the French. The male fur traders frequently married into different tribal nations and, at times, embraced some or all of the culture of their new tribe, while others fought for control of the group away from traditional leadership.

Using trade and technology as bargaining chips with various tribes, the Spanish, English, and French competed for support and assistance in their quarrels against each other. Trade is much larger than an exchange of goods, and affects politics, culture, and societal ideas. The introduction of new technology and new conflicts changed American Indian trade forever and shaped a great portion of United States commerce.

Jean Pierre Chouteau was part of a family that successfully traded with the Osage (3105, Oklahoma Historical Society Photograph Collection, OHS).

Popular trade goods included glass trading beads (images courtesy Ellensburg Public Library).

Map of the Three Forks area, sketched by Tom Meagher (WATMAP.FOREMAN.0002, Grant Foreman Collection, OHS).