Commerce in Oklahoma

World War II

The material and labor needs of World War II ended the Depression. The introduction of several defense-related industries and military bases brought short and long-term advantages to Oklahoma. Immediately, Oklahoma companies were given opportunities to gain the business of the federal government. The emergency speeds at which military bases arrived meant money was delegated to produce results more rapidly. Companies hired more employees to help them work efficiently and quickly. Jobs were created in nearly every industry as these industries and military bases ramped up. Demands from the federal government to outfit its military and meet the obligations of allies moved production, profits, and wages into high gear. The early 1940s brought a time of upward economic movement and reversed the high unemployment numbers.

Construction after a fire on Tinker Air Force Base in 1946 (22596.12, Jacqueline D. Wright Collection, OHS).

Schoolchildren had to use old Tinker facilities because the size of the school district grew so rapidly (2012.201.B0149.0804, OPUBCO Collection, OHS).

The military-industrial complex introduced a new business sector into Oklahoma’s economy and rapidly increased the population of Oklahoma. The lack of economic diversification that caused severe consequences in the last two decades seemed to fade, but the state remained dependent on unstable markets. Throughout World War II, another shortcoming became apparent: the highways. The roads across Oklahoma were very undeveloped. Many of them were unpaved and most of the major roads we are familiar with today did not exist. Unpaved roads were inconvenient for the federal defense programs, as they often needed fast transportation for soldiers or supplies. This led to the development of a plan for a network of superhighways and is one of the reasons Oklahoma is now known as a major crossroads in the nation.

This photograph shows I-35 in 1970(2012.201.B0289B.0340, OPUBCO Collection, OHS).

“Dedication of I-35 From Ardmore to Davis,” August 17, 1970 (1362, William A. McGalliard Historical Collection, OHS).

These roads, approved by the 1956 Interstate Highway Act and constructed in the 1960s–70s, would stimulate the economy in several ways. Fast and more direct transportation for goods, the creation of jobs in construction and urban planning, and easier travel for the average person increased opportunities to explore new markets and network with other businesses. Even though the need for more roads became glaringly apparent in the 1940s, it would provide the greatest economic benefit 20 and 30 years later.

Manufacturing opportunities also increased in the 1940s. Production of goods for the war effort and increased demand overall led to a slight transition away from an extractive economy. Where previously most goods that came from Oklahoma were raw materials (cotton, zinc, lead, wheat, etc.), the increase in manufacturing meant Oklahoma was now producing finished goods, adding a secondary sector to the economy. The increase in manufacturing continued to grow and helped to counter the lack of diversification in the state. The manufacturing industry relied on the military bases in Oklahoma, and vice versa.

ACME Manufacturing in 1957 (21412.M454.22, Z.P. Meyers/Barney Hillerman Photographic Collection, OHS).

Agriculture was beginning to evolve and saw drastic changes in the 1940s–50s. The Rural Electrification Administration, established in 1935, brought electricity to farmers across the state. Conveniences common in urban areas, like running water, indoor plumbing, and refrigerators, were reaching those in rural areas as well. By 1950, more than 66 percent of farmers had electricity, and the rural standard of living improved. At this point, the restructuring of Oklahoma’s agriculture became apparent. Farms were decreasing in number but increasing in size, and would continue to do so for the next 30 years.

The Dust Bowl and drought continued to harm the agricultural industry, and people in every corner of the state faced hunger and homelessness. “Hooverville” tent cities were set up in most large cities, named after Herbert Hoover who was president during the beginning of the Great Depression. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, having faced such strong political obstacles, couldn’t build the stable economy needed in Oklahoma on its own. Its worker programs saw the most success here, like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and Works Progress Administration. Both programs managed to create jobs and cultivate stability in Oklahoma. They assisted in solving problems in several ways. They built roads, which improved infrastructure. Soil conservation projects helped the land recover from the drought and overwork. The CCC built state parks, which established areas dedicated to native vegetation and opportunities for immersion in nature. These programs provided some opportunity to rise from the Depression, but it wasn’t until the demands of World War II and the end of the devastating drought that Oklahoma’s economy could truly recover.

Guthrie CCC camp, 1936. Photograph by Jim Slack (20778.AG.SCS.OKLA.5115, Edd Roberts Collection, OHS).

Civilian Conservation Corps #899 in 1933 (21023.9, OHS Photograph Collection, OHS).

The Great Depression was extended by political disagreement. The state of Oklahoma was, and still is, greatly affected by the events of the 1920s and 1930s. The population of the state would remain strikingly low until the 1970s, but the oil, mining, and agricultural industries would grow to be relatively strong in the next few decades. The railroads, which had faced a sharp decline during the Depression, would strengthen during World War II, only to fall afterward. Coal mining became less common as zinc production increased. The arrival of the military-industrial complex would drastically affect the area, and the importance of balance in economics would be reestablished time and time again.

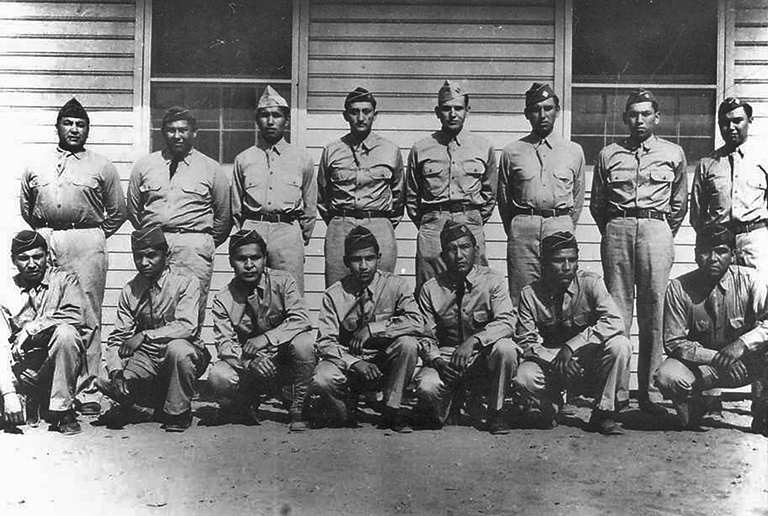

Comanche Code Talkers made a significant contribution to the victory in the Pacific during World War II (image courtesy of the United States Army).

The federal government chose Oklahoma for new military development for several reasons. Governor Robert S. Kerr had repaired the state’s relationship with the Roosevelt administration and secured a large share of federal defense funds for the state. Geographically, Oklahoma is central, protected, and mostly flat with space for development and growth. Climatically, Oklahoma is relatively mild, allowing for year-round work and lower heating expenses. As the war progressed, the federal government established prisoner of war (POW) camps in various parts of Oklahoma for many of the same reasons. The issue of unemployment evolved into a shortage of workers, which led to women’s entry into the workforce. Discoveries of oil reached new highs, as did production of the new technology of liquefied natural gas. People of every race and creed assisted in the war effort, whether they worked at the in-state flight training facilities, fought on the frontlines in Europe, or filled one of the thousands of positions in between. American Indian soldiers from Oklahoma served vital roles in the war as Code Talkers. The few Japanese Oklahomans faced additional discrimination due to the nature of the war, but many of them also served in the armed forces.

The banking industry was devastated by the Great Depression. However, it saw some reprieve during World War II and reduced its reliance on the agriculture industry, expanding towards military development and later towards housing and a variety of other trades. They maintained their relationship with agriculture by creating new farming-based departments. Banks cultivated economic growth through the creation of the Oklahoma Finance Authority in the 1950s, promoting startup businesses and offering deals to new entrepreneurs.

The end of World War II left the state with strong economic momentum, and industries built out of necessity became mainstays of Oklahoma that still function today. These industries, combined with those that were long established, revitalized the Oklahoman economy and began a new era for the state. Despite the usual postwar instability and inflation that arises as demands change, the next decade was relatively stable. The petroleum industry began a slow nationwide descent in the 1950s, but its influence on Oklahoma’s economy continued to be strong. Railroads, specifically those that carried passengers rather than goods, dwindled as private automobiles became increasingly popular. Many rail lines shut down due to a lack of usage. The invention of mechanical air conditioning expanded business opportunities in the hotter summer months. The fight for civil rights increased and saw substantial results, and the movement evolved as African American communities united to protest discriminatory practices and systems, both legally and physically. In Oklahoma triumphant civil rights cases gained attention, including Sipuel vs. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma (1948) and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education (1950). The developments in civil rights for African American communities meant increases in economic opportunities and decreases in legal and physical barriers.

Civil rights leaders such as Amos T. Hall, Thurgood Marshall, and Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher expanded economic opportunities for Black Oklahomans. (2012.201.B1268.0091, OPUBCO Collection, OHS).