Owen & The Federal Reserve Act

My Dear Senator:

Now that the fight has come to a successful issue, may I not extend to you my most sincere and heartfelt congratulations and also tell you how sincerely I admire the way in which you have conducted a very difficult and trying piece of business? The whole country owes you a debt of gratitude and admiration. It has been a pleasure to be associated with you in so great a piece of constructive legislation.

Cordially and sincerely yours,

Woodrow Wilson

Owen acquired various important committee positions, some of which he had held in his first term such as his position on the committees of Indian Affairs and Public Health and national Quarantine. But he could have no more important an assignment than chairman of the new Committee on Banking and Currency. There was a ground swell of support, even demands, throughout the country that the banking system be reformed. Large and small bankers, most businessmen, and the general public were convinced that only major restructuring would stabilize the system. This consensus for reform was a result of several recent events. During the 1890s and early 1900s a growing number of bankers began criticizing the unstable nature of banking and calling for reforms. These critics were in the minority, however, until the Panic of 1907, which shocked many bankers who had previously opposed altering the system. The Aldrich-Vreeland Act of 1908, with its provisions for emergency currency and temporary banking associations, was designed to avert another serious panic, but most knowledgeable observers realized that it was a mere stopgap measure. The banking system needed a complete restructuring.

This conclusion was reaffirmed by the National Monetary Commission, an investigative body headed by Senator Aldrich and created under the Aldrich-Vreeland Act. In 1912, after several years of periodic study, the commission submitted a proposal, known as the Aldrich Plan, which was primarily based on the ideas of Paul M. Warburg, a partner in the investment firm of Kuhn, Loeb, and Company and long-time advocate of banking reform. This bill called for the creation of a large central bank totally under bankers’ control and with fifteen branches throughout the country. This bank, known as the National Reserve Association would issue its own currency backed by gold and commercial paper. It would hold a portion of the reserves of member banks and discount loans, thereby making banking more flexible. Although the bank would be a depository for governmental funds, the government would select only four out of the nine members on the governing board.

When the details of the bill became public in 1912, the reaction was mixed. The National Citizen’s League for the Promotion of a Sound Banking System, a Chicago-based organization of reform-minded bankers, immediately endorsed the principles of the bill. The Democrats did not. Any proposal with Aldrich’s name attached was bound to be rejected by the Democrats. Also, they particularly objected to strong central bank features and the absence of governmental control, and they feared that Wall Street would dominate in such a system.

Their fear of Wall Street was reinforced in 1912 and 1913 by the investigations of the Pujo subcommittee of the House Committee on Banking and Currency, which was chaired by Louisiana Representative Arsene Pujo. Under the direction of special counsel Samuel Untermyer, an ambitious and probing lawyer from New York, the Pujo subcommittee revealed a shocking system of interlocking directorates between big banks and big corporations, or, in other words, Wall Street domination of the economy. Ironically, the revelations of the subcommittee stirred public support for a restructuring of the banking system that provided most of the changes that bankers themselves had been advocating.

As the Pujo subcommittee investigated, another subcommittee of the Committee on Banking and Currency began the process of preparing a reform bill. Its chairman, fiery, quick-tempered Carter Glass of Virginia (who was coincidentally from Lynchburg), began drawing up a bill. Glass was a newspaperman rather than a banker; therefore, he depended heavily on the subcommittee’s special advisor, H. Parker Willis, an economics professor who was connected with Warburg and other prominent advocates of banking reform. They drafted a measure that had most of the features of the Aldrich Plan, except it was to have no central control because of a belief that the public would reject such a provision. They discussed their plan with President-elect Wilson in December 1912 and January 1913. Wilson insisted that a central governing board should be added.

Thus Willis and Glass returned to work and completed a revised bill in May. It provided for a system with fifteen or more regional banks. Like the Aldrich Plan, these banks would issue money backed by commercial paper and gold, hold portions of reserves for banks, and discount loans to enable national banks to acquire money when they ran short on liquid assets. Six presidential appointees and three representatives of the bankers would oversee the Federal Reserve Board.

Soon after Owen became chairman of his committee in March 1913 he learned that Glass was already in the process of preparing a bill. Owen, therefore, quickly drafted his own measure to submit to the president and to William Gibbs McAdoo, the Secretary of the Treasury. Owen’s bill called for the creation of a National Currency Board, and many of its provisions represented a departure from his previous views on reform. As a reform-minded, small town banker, Owen had recommended fairly limited alterations in the banking system, such as an emergency currency fund controlled and distributed by the United States Treasury during panics. He also had advocated postal saving banks for timid and easily panicked small depositors. In the early years Owen had also opposed “assets currency” (non-governmental currency backed by commercial paper of private banks). Most advocates of banking reform wanted such currency. In 1913, when he submitted his new proposal for a National Currency Board, Owen altered his position by calling for an assets currency. However, he still insisted on the government having final legal responsibility for the currency.

Also, Owen shifted from his earlier ideas by calling for a central national-level governing board that would oversee eight regional banks. This governing board would be appointed by the president and would not be under the control of private bankers. This provision for total governmental control and the requirement that the currency be ultimately supported by the government were the two most important differences between Owen’s proposal and the Aldrich and Glass plans. Owen also decided not to include bank guarantees and regulation on stock market gambling in his bill, although he had previously supported such ideas.

In late March Owen began meeting with Glass and officials of the administration. He was given a cold reception. Naturally, he wanted to help frame a banking reform measure. Just as naturally, Glass was reluctant to give up the control over the process that he had acquired through his earlier work.13 Colonel Edward M. House, Wilson’s private advisor and confidant, suggested that Secretary McAdoo present the Glass Bill to Owen as if it were a proposal of the administration. “Owen will be more likely to accept it as a Presidential measure than as a measure coming from the House Committee on Banking and Currency,” he wrote in his diary. Later, when House met with Owen, McAdoo, and Glass for dinner in Washington he found it necessary to “put Owen in good humor so that he would be receptive to our views.”15 Glass and his aide, Willis, likewise viewed Owen as temperamental because he had been left out of the original steps of drawing up a bill.

Owen sought cooperation from others instead. He found a ready ally in Samuel Untermyer, the investigator who had written the Pujo report. Untermyer was a high-powered attorney who had represented small companies against corporate giants but, on the other hand, had won suits for such powerful clients as the Rockefellers. He was immensely disliked, even despised, by the bankers of Wall Street. Untermyer had also alienated Glass by using his position on the Pujo subcommittee to try to take control of banking reform from Glass. However, Owen immediately became friends with Untermyer, probably because he New Yorker insisted on governmental control of the banking system. Also, Untermyer--like Glass--was coincidentally a native of Lynchburg.

Beginning early in May 1913, Owen stayed with Untermyer periodically in his large mansion, “Greystone,” at Yonkers, New York. Overlooking the Hudson River, his estate was a famous showplace, especially with its elaborate greenhouses. Untermyer used his home to impress people and to offer a warm hospitality that helped win friends. With Owen often present, Untermyer invited several influential politicians and bankers to conferences at Greystone. Bryan, House, Warburg, and many others met to discuss ideas on anticipated currency legislation. On May 18 Owen and Untermyer debated with Warburg for seven hours over the concept of governmental control of the proposed banking system. Then, when Warburg sailed for a European vacation two days later, he took a copy of Owen’s bill to critique. Over the next several days Owen sent copies to other New York financial leaders, such as Frank A. Vanderlip and Benjamin Strong. One of the financiers, who insisted on remaining anonymous, liked the simplicity of Owen’s plan. Most bankers, however, rejected major portions of it. The bankers particularly objected to the governmental backing of currency and governmental control of the board. Owen, the common man’s advocate, was forced to appeal to big bankers for approval of his bill.

When they turned it down, he began considering a proposal submitted by secretary of the Treasury McAdoo, known as the National Reserve Plan. Under this measure, McAdoo’s department would have operated a government-controlled central bank. With the addition of McAdoo’s proposal, Wilson had three competing measures before him by late May 1913, and with McAdoo, Glass, and Owen each crusading for their respective plans. Although prominent bankers had rejected Owen’s plan, McAdoo’s ideas were even less popular, and the Glass Bill received only lukewarm support. Ultimately, the final decision rested with President Wilson. After considering all the plans, he selected the Glass Bill on June 7, 1913, as the official plan of the administration.

This was not the end of the struggle. Owen continued to insist that the Federal Reserve Board should be controlled by the government and that the currency should be the liability of the government. If bankers exclusively controlled the system, he argued, large banks in major cities would dominate and would continue to manipulate money to the detriment of small businesses. William Jennings Bryan, now secretary of state, allied with Owen and insisted on the same stipulations. To reach a final decision, Wilson met for several hours with Owen, McAdoo, and Glass at the White House on June 17. Glass pleaded for strong domination by bankers, while Owen argued for governmental control. Wilson delayed his decision and the following day announced his support for the Owen-Bryan point of view. A final draft of the proposal was quickly prepared. On June 19 it was released to the public. One week later Owen and Glass introduced identical measures in both houses of Congress.

Now called the Glass-Owen Bill, it was fundamentally the same as the original Glass-Willis proposal. But Wilson’s addition of a central reserve board and the Owen-Bryan governmental control made the measure somewhat different than the original plan. In its final form the act called for a system of eight to twelve district Federal Reserve banks, with each having its own boards elected by member banks. Each regional bank would hold reserves for its member banks and would set discount rates for the region. The governing Federal Reserve Board was to have seven members, two of whom were the Secretary of the Treasury and the Comptroller of the Currency. The remaining five members were to be appointed by the president. This board would generally regulate the system, but in the final bill it was denied the power of setting discount rates. Theoretically the plan took control away from Wall Street and distributed it to the regional banks; thus, it was somewhat of a victory for bankers outside of the northeastern section of the country.

The bill was a compromise, yet one that Wilson, Glass, Owen, and McAdoo were willing to support. They immediately set out to gain approval for this bill and the task was not easy. Practically all bankers who expressed opinions were opposed to at least some portions of the bill. Those in New York feared the “Owen-Bryan heresy” of governmental control. Some bankers in large Midwestern cities disliked the stringent regulations, and “country” bankers of the small towns wanted greater safeguards against big banks.

Facing numerous complaints, the backers of the bill began their crusade to gain support, and Owen contributed substantially to this promotion. On June 20 he addressed a gathering of the Virginia Bankers Association and explained the plan. Two days later at the Waldorf Hotel in New York City he conferred with nationally prominent bankers, all members of the Currency Commission of the American Banker’s Association. Later in June he again met with several of these same representatives at a White House conference that also included Wilson, Glass, and McAdoo. During this discussion, the financiers persuaded the sponsors of the bill to make several modifications, but none changed it fundamentally. In these meetings, in his speeches, and in his numerous letters on the subject, Owen defended his two pet provisions--governmental control of the Federal Reserve Board and governmental backing of the currency. Eventually a majority of bankers began to support the plan, probably fearing a less desirable proposal might replace it.

Despite strong propaganda from Owen and his allies, the bill underwent a hard-fought and frustrating struggle for passage. In the House of Representatives the strongest opposition came from various southern and western radicals who were former supporters of Bryan. To appease these rebels, Wilson promised to destroy the interlocking directorates of the money trust in the upcoming anti-trust legislation; then he compromised by allowing some rediscounting of short-term agriculture paper; and he threatened, begged, and bargained with the congressmen. After considerable delay, the measure passed the House of Representatives on September 18, 1913.

The struggle for passage in the Senate was even more arduous. Strong opposition came in the Senate Banking and Currency Committee. In addition to Chairman Owen, only three pro-administration Democrats served on the committee. Three other Democrats, James A. Reed of Missouri, James A. O’Gorman of New York, and Gilbert M. Hitchcock of Nebraska, opposed the bill for both selfish and philosophical reasons. The remaining five Republicans on the committee likewise were generally unfriendly to the measure.

The committee members who opposed the bill were so hostile and uncompromising that even Owen seemed to falter in his support of the bill. During a meeting on August 19, 1913, Owen hinted he might be willing to drop the provisions for the regional reserve banks. He also indicated the committee might eliminate a requirement that all national banks join the system. The next day, after newspapers in New York City gave alarming attention to his remarks, Owen reconfirmed emphatically his support for the bill. Whether Owen was actually intimidated or was simply trying to manipulate his adversaries on the committee, his erratic behavior reflected the domination of the hostile majority on the committee.

As the debate continued, Owen showed fewer signs of compromise, but he could do little to move his committee toward approval of the bill. In early September, 1913, hostile members of the committee insisted on time-consuming hearings, probably in an attempt to block progress. Their justification for the hearings was that numerous bankers had continually called for testimony but had been given only limited input into formulating the measure. Although Owen did not favor the hearings, the opposition prevailed. The result was a delay lasting two months.

Most of the information collected at the hearings was not new, and most of the witnesses had already been consulted several times. Owen arranged for his old friend Shibley and his new ally Untermyer to give testimony; they actually supported strong governmental influence. Also appearing before the committee was Vanderlip, who produced a proposed substitute at the request of several of the troublesome senators. His proposal called for a system similar to the Glass-Owen Bill, but, with surprisingly thorough governmental control over the system. Because Vanderlip was a big banker, Wilson and his friends believed he was trying to divide the Democrats between his “radical” plan and the Glass-Owen Bill, and thereby scuttle any legislation.

To counteract the divisiveness on his committee, Owen began holding conferences with committee members every evening to resolve differences. Wilson’s patience deteriorated as the debate lengthened. He closely followed the committee’s progress and used all the power he could to pressure the rebellious Democrats on the committee. By early November, 1913, Senators Reed and O’Gorman finally fell into line. At this point, six Democrats were then supporting the original Glass bill, and they agreed to report it with some amendments to the full Senate. This amended plan was known as the Owen bill. But Hitchcock remained stubborn and allied with the Republicans on the committee to produce a counterproposal called the Hitchcock Bill, which was based on Vanderlip’s plan.

In late November the committee submitted both reports without recommendation to the full Senate. In the lively debate that followed, Owen became the principal advocate for the administration. His performance revealed a substantial shift in his position that had occurred over several months. In May he had opposed Glass and Willis in their attempt to exclude governmental control of the Federal Reserve Board. He had even flirted with McAdoo’s proposal of total governmental control. Now, in December, he argued that the government should be limited in its control. He warned senators that the Hitchcock-Vanderlip Plan for strong governmental control was a gimmick to defeat all proposals.30 And then he said:

If we are ready for Government ownership of the banking business and to have the Government drive all the banks out of the banking business, that is one thing, but we are not proposing to have these adverse policies merged with a bill that is intended to be a bankers’ bill, and intended to protect the banks and enable them to perform their proper functions.

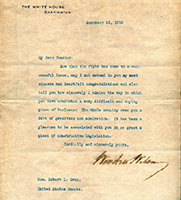

He was obviously playing the role of the lawyer-lobbyist, arguing a viewpoint that he did not necessarily embrace personally. This sort of stalwart advocacy for the administration endeared him to Wilson, who always had a high opinion of the Oklahoman. It provided little support, however, for the truly progressive viewpoint that the federal government should play the role of protector of the public interest. The Senate finally passed the Owen Bill on December 19. In the next few days, remaining details were worked out in the House-Senate conference, and the final version quickly passed both houses. Wilson promptly signed it on December 23. The president was delighted.32 He sent letters of congratulations to those most responsible for passage. In a note to Owen he wrote, “May I not extend to you my most sincere and heartfelt congratulations, and also tell you how sincerely I admire the way in which you have conducted a very difficult and trying piece of business?”33 Owen, too, was pleased, even though he had been compelled to accept compromises. Clearly, when Wilson finally decided what direction to follow, Owen dutifully obeyed him. Perhaps he hoped that more progressive reforms could be enacted later.

Regardless of his hopes and designs in 1913, Owen later argued that many of his major demands for reform had been embodied in the Federal Reserve Act. He was especially proud of the supposed governmental control of the national board. Over the years he came to view himself as the principal architect of the Federal Reserve Act. However, there was a virtual host of other claimants for that honor. Warburg, Willis, and Glass each believed they were the true authors. And a half dozen other politicians and banking experts demanded at least a share of the credit. From the beginning of the process they had distrusted one another and belittled the others’ contributions. For instance, in July 1913 Warburg wrote to Colonel House describing the abilities of Glass and Owen:

Regardless of his hopes and designs in 1913, Owen later argued that many of his major demands for reform had been embodied in the Federal Reserve Act. He was especially proud of the supposed governmental control of the national board. Over the years he came to view himself as the principal architect of the Federal Reserve Act. However, there was a virtual host of other claimants for that honor. Warburg, Willis, and Glass each believed they were the true authors. And a half dozen other politicians and banking experts demanded at least a share of the credit. From the beginning of the process they had distrusted one another and belittled the others’ contributions. For instance, in July 1913 Warburg wrote to Colonel House describing the abilities of Glass and Owen:

I have preached the gospel of reform on the lives now adopted at a time when Mr. Owen and Glass had not yet began to study the alphabet of banking...but neither of them could draw a foreign bill to finance a shipment of cotton. I know it, because I have been examined by both of them.

During the 1920s each of the major participants wrote books about their roles in fathering the Federal Reserve Act and attempted to prove that the other claimants were mere secondary participants in the process. The debate between Glass and Owen became particularly bitter, resulting in open, vitriolic aspersions on each other’s character in the 1930s when the Federal Reserve System underwent major changes.