Oklahoma Education

Segregation in Schools

After the Civil War and the end of slavery in the South, white citizens attempted to ensure Black citizens would not be able to live on an equal basis with their white counterparts. Whites often subjected Black citizens in their towns to violence and lynching to pressure them. Although some Black residents fled the violence of multiracial towns to form All-Black towns, many Black residents remained. Unable to create separate towns for whites and Blacks, white lawmakers passed laws to separate the lives of the two racial groups. A new territorial legislature banned racial mixing in school, and throughout the US, many protested the change. Schools were one of the first places of social interaction for children, so decisions about education could affect the ways Black and white students interacted many years down the road. In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Supreme Court supported these separate or segregated schools for Black and white students, arguing the schools could be “separate but equal” and not violate the constitution. However, in reality, the segregated schools were anything but equal. Schools for Black students lacked the resources and funding that white schools enjoyed. Not only were class sizes larger, but it was common for Black schools to have outdated textbooks and crumbling facilities, making it difficult to learn. Following decades of protests and community organizing by Black civil rights leaders in Oklahoma, such as Clara Luper, segregation in schools was eventually overturned. The ruling in Brown v. Board of Education decided “separate but equal” was unconstitutional and demanded integration. Given that Oklahoma required separation of schools, legislators needed to work hard to undo it.

In order to integrate schools, Governor Raymond Gary came up with the idea to rearrange funding for schools based on attendance. He wanted to place all school taxes into a common school fund. He also wanted to end the county tax that kept the separate schools open. He proposed that in return, school systems will close the separate schools and combine them with the smaller schools. The Oklahoma Legislature passed an amendment for the funding method on January 7, 1955. Governor Gary signed this bill into law on March 9.

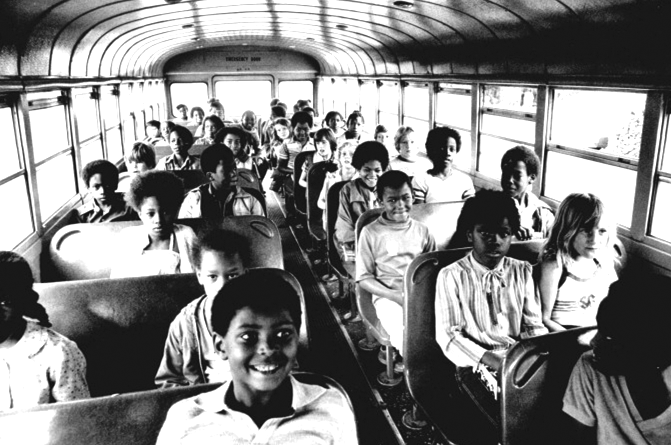

However, racial segregation did not end. Most schools remained segregated into the 1960s. By 1956, there were 273 integrated schools in Oklahoma. Despite that, there was still segregation among students, depending on where they lived within the district. Segregation continued even after the federal court cases Dowell v. Oklahoma City (1963). In this case, the school district of Oklahoma was sued in attempt to gain admission for Dowell’s son to an all-white high school. Not long after, on July 11, 1965, US district Judge Luther L. Bohanon claimed the dual school system operated by the Oklahoma City school district violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution. Judge Bohanon ordered Oklahoma to come up with integration plans. It took seven years to get this process started. This resulted in the creation of cross-district busing in 1972.

Students riding the bus (2012.201.B0982.0059, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

US District Judge Luther Bohanon (2012.201.B0095.0689, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).