The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

COAL-MINING STRIKES.

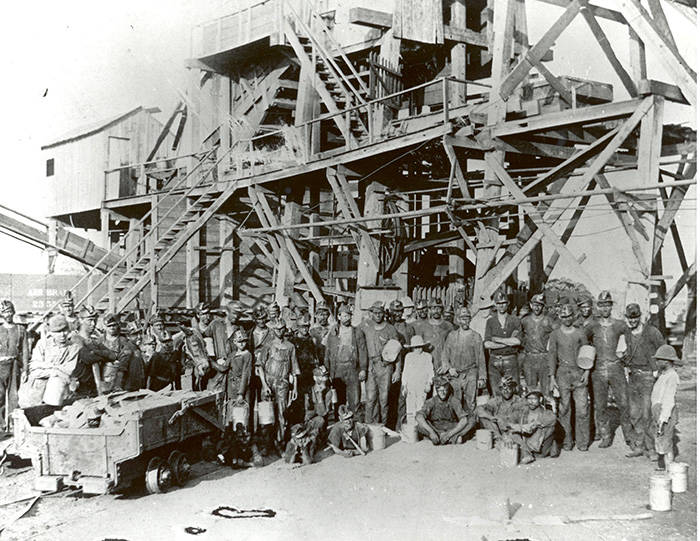

The national Knights of Labor sponsored the first union in Indian Territory when they organized coal miners in 1882. As leader of the coal miners' union in Indian Territory and early Oklahoma, Peter Hanraty stressed negotiation as the means for resolving most labor conflicts, but he recognized that strikes were often necessary. Such was the case when the Indian Territory Coal Companies reduced wages by 25 percent, effective April 1, 1894, due to allegedly depleted markets and reduced production, neither of which was the case. In 1891 production had been 1,091,032 tons, worth $1,897,037; production two years later was 1,252,110 tons with a value of $2,235,209.

After almost six weeks of fruitless negotiations, Hanraty helped organize a strike. On May 10, 1894, he led a march involving about one thousand people from the Lehigh and Coalgate area to a mine owned by the Williamson Brothers, because work there had continued. Almost fifty women carrying banners were in the lead, followed by nearly one hundred miners with rifles and shotguns. They were followed by the Coalgate Band. Most of the remaining demonstrators, including children, carried clubs. No violence occurred, and the Williamson Brothers agreed to stop work.

After only a few weeks, however, the strikers became demoralized in the face of resistance from the Choctaw government, and United States authorities, and mine operators. Choctaw Chief Wilson N. Jones and Indian Agent Dew N. Wisdom asked Secretary of the Interior Hoke Smith for federal troops. Smith complied, and two companies were sent from Fort Reno. Many of the miners were declared "intruders" for having no permits to be in Indian Territory, and fifteen were apprehended and expelled to Arkansas.

A lack of funds also crippled the strike. After two and one-half months, on July 1, 1894, the miners returned to work with nothing gained. They could not feed their families. Hanraty realized that successful strikes would require emergency funds for strikers. Therefore, he initiated the practice of withholding dues for that purpose, replacing a previous system of voluntary contributions from members.

In February 1899 a joint conference of miners and operators was held at Fort Smith, Arkansas. The primary purpose was to sign a wage agreement. However, the operators of the Kansas and Texas Coal Company, the Atoka Mining Company, the Osage Coal Company, and the Choctaw Coal Company, known collectively as "the Big Four," refused to recognize the conference or accept the agreement. This resulted in a strike that lasted for nearly five years and proved disastrous to several mining areas of the Southwest.

The strike was among the hardest fought of any in regional labor history. Mine operators imported African American strikebreakers from Alabama and West Virginia so that mining could continue. These Black "scabs" abided by the Jim Crow laws segregating them from the white population. However, their presence increased racial tensions in the mining communities. Miraculously, there were no major incidents, but threats and harassment by white miners caused much unpleasantness for both Black and white.

Hanraty sympathized with the harassed miners; they were all workers and expressed a comradeship that only they understood. He sought a fair settlement while attempting to avoid either discouragement among the miners or a case for federal intervention. With his leadership a decisive victory over management was achieved in 1903. The resulting agreement, which established the United Mine Workers (UMW) as a major force in the coalfields of Indian Territory, is still considered the most important document in labor relations for the coal-mining industry in the Southwest.

During World War I coal miners received pay increases that brought the scale to $7.50 a day. At the end of the war mine operators reduced the wages to pre-war levels even though coal prices remained high and demand heavy. About seven thousand miners in Oklahoma walked out in October 1919. At the mine operators' request, Gov. James B. A. Robertson sent two thousand National Guard troops to southeastern Oklahoma. However, the operators knew that they were losing great profits. They agreed to pay $5.50 a day and by June 1920 increased the scale to $7.50 a day.

In the 1920s union discontent and wage negotiations continued. In March 1924 the Southwestern Coal Operators Association agreed to pay $7.50, a day, but as the coal market declined, they refused to abide by the agreement and offered only $5.00. In September 7,500 workers went on strike. The strike finally ended in 1927 with the miners accepting $5.00 a day scale and often less. The union had been weakened, but by November 1931 it had regained enough strength to call a strike of its 1,500 members in the Henryetta field. By the end of December the union and the operators agreed on arbitration, and the strike ended.

Afterward, no significant strikes took place for four decades. In December 1977 three coal mines that produced about 40 percent of Oklahoma's soft coal were closed by the United Mine Workers. This included the Peabody Coal and Mine Company, located between Nowata and Vinita, and two mines owned by Garland Coal and Mining near Stigler and Bokoshe. The Peabody mine had approximately 174 members and Garland ninety members. The strike was brief, and the miners gained little.

Trouble brewed again in 1981 when the Garland Company replaced striking UMW workers with nonunion miners. Although the national strike ended ten weeks later, the company would not rehire the Oklahoma participants. Violence occurred over three years as this labor dispute continued. Gunshots were fired at two national union representatives, a security guard was wounded, other gunplay incidents were reported, and two sticks of dynamite exploded at the home of a Garland official. By 1984 most union miners had found other jobs, and the union used court mediation to try and collect pay and reimbursement from the Garland firm. By the 1990s mining activity and labor disputes dwindled in Oklahoma.

See Also

Learn More

Fred W. Dunbar, Peter Hanraty: Champion of the Working Man (New York: Carlton Press, 1991).

Federal Writers' Project of Oklahoma, Labor History of Oklahoma (Oklahoma City, Okla.: A. M. Van Horn, 1939).

Frederick Lynne Ryan, The Rehabilitation of Oklahoma Coal Mining Communities (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1935).

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Fred W. Dunbar, “Coal-Mining Strikes,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=CO005.

Published January 15, 2010

Last updated July 24, 2024

© Oklahoma Historical Society