NEW DEAL.

In 1932 New York Gov. Franklin D. Roosevelt campaigned for the presidency with the slogan, "A New Deal for America." The Democratic nominee promised a vigorous use of the federal government to fight the nation's economic depression. Overwhelmingly defeating Pres. Herbert Hoover in the November election, Roosevelt and his "Brain Trust" formulated the New Deal prior to his inauguration in March 1933. For the next five years the New Dealers created agencies, boards, commissions, and programs to combat the Great Depression. Historians have described the New Deal as "revolutionary," "a drastic new departure," or "an exceedingly personal enterprise." However, in Oklahoma the New Deal had few long-lasting consequences.

Oklahoma's economy had become depressed following World War I. Large surpluses of agricultural commodities drove prices downward, and farm tenancy, endemic in eastern and southern Oklahoma, worsened as more than half of the state's farmers labored on land owned by others. The discovery of oil and natural gas brought brief prosperity to some areas of the state, but by 1931 overproduction sent oil prices to disastrously low levels. Compared to other states, Oklahoma suffered the third-greatest decline in income between 1929 and 1932.

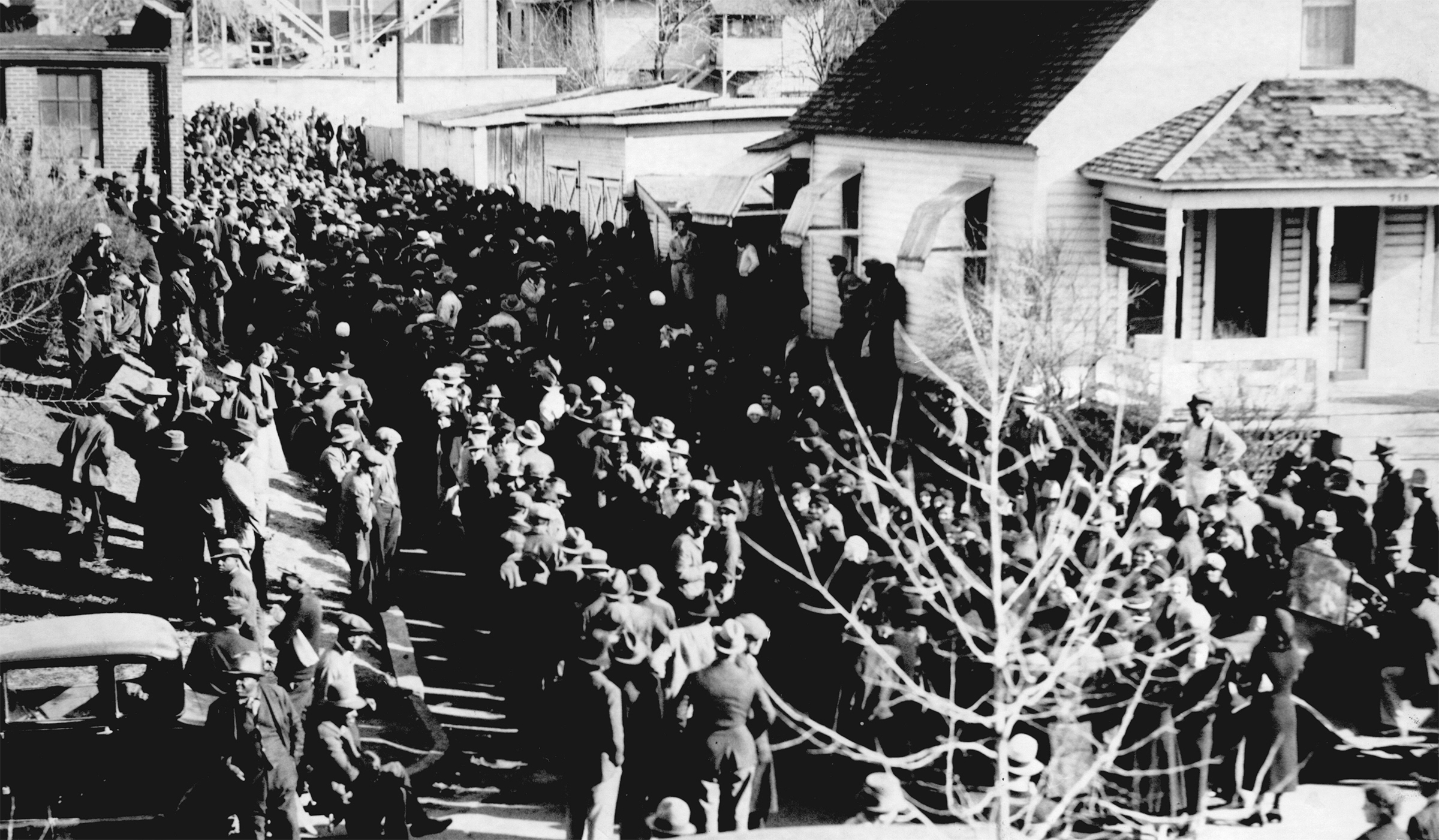

Compounding the economic plight, a severe drought began in 1932, and the far western part of the state, notably the Oklahoma Panhandle, became part of the Dust Bowl. Winds blew away the topsoil, forcing many farmers to leave. Known as "Okies," they fled westward to California and Arizona. There they joined eastern Oklahoma tenant farmers displaced by land consolidation and mechanization. Thousands of farmers were being "blown off" or "tractored off" the land.

In 1930 economically distressed farmers helped elect agrarian William H. "Alfalfa Bill" Murray as governor. He failed to generate relief for Oklahoma's poverty stricken, because he did not have the legislature's support. Murray "fought" the Great Depression by sending the National Guard into the oil fields to try to prevent "hot" (illegal) oil production and by allowing the homeless to plant gardens on the Governor's Mansion lawn.

Murray's notorious eccentricities attracted national attention, which he misinterpreted for popular acclaim. He entered the Democratic presidential contest in 1932, launching a scurrilous attack on Roosevelt. Therefore, the new administration viewed Murray as a political pariah and battled him for three years. Murray used Public Works Administration (PWA) relief funds for political purposes and failed to obtain state matching funds for Civil Works Administration projects. Consequently, the New Dealers removed most programs from the governor's control, and Oklahoma received few federal relief dollars.

The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) sought to aid farmers by paying landowners not to grow crops or raise livestock. Oklahoma's land-owning farmers tilled fewer acres, but they bought fertilizer and machinery, which increased output. More than one million farmers and their families received AAA payments, but federal dollars represented only one-sixth of the total agricultural income in the state. Oklahoma cotton farmers rejected the Bankhead Cotton Control Act of 1934, refusing to participate.

U.S. Rep. Ernest W. Marland, a former Republican and oilman, ran for governor in 1934 with the slogan, "Bring the New Deal to Oklahoma." Denouncing the obstructionism of Murray's administration, Marland proposed a public works program, old age pensions, unemployment insurance, and tax code reform as well as state-owned industries, flood control, and a state planning board. Easily elected, Marland sent his proposals to a hostile, rural-dominated legislature that rejected most of his ideas. However, an old age pension system was created, funded by a dedicated sales tax. Although Marland had excellent relations with Roosevelt and his administration, the lack of state matching funds precluded all but a few major projects. The Grand River Dam Authority constructed a hydroelectric dam on the Grand River using PWA funds, but it and the Red River Denison Dam represented the only significant "pump priming."

Oklahoma joined Texas and other oil-producing states in an effort to limit output and raise prices. The National Recovery Administration did little to control production, leading the states to form the Interstate Oil Compact in 1935. State governors, including Marland, initiated this effort.

By 1938 a conservative reaction had developed in Oklahoma, influenced by anti–New Deal legislators and a metropolitan press adamantly opposed to the Roosevelt administration. In that year a former Republican, Leon Phillips, won the governorship and launched a war against Washington-inspired programs. The New Deal in Oklahoma, such as it was, ended.

A few New Deal agencies proved to be successful in the Sooner State. The Oklahoma Civilian Conservation Corps was one of the largest in the nation. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) provided modest funds for constructing roads and bridges and for building schools, courthouses, and National Guard armories. However, there were few Reconstruction Finance Corporation loans in Oklahoma, and agencies such as the Resettlement Administration had virtually no tangible impact. Shelterbelts were planted along roads in western Oklahoma, but only the coming of rain and World War II revitalized the agricultural economy.

Few New Deal legacies could be found in Oklahoma after 1940. The Great Depression, the Dust Bowl, and demographic changes had loomed larger than federal programs. The political basis for the New Deal, the "Roosevelt Coalition," simply did not exist in Oklahoma. The New Deal in Oklahoma was neither "revolutionary" nor even evolutionary in nature. The conservatism of Sooners precluded the changes wrought in other states during the 1930s.

Learn More

Keith L. Bryant, Jr., Alfalfa Bill Murray (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968).

Keith L. Bryant, Jr., "Oklahoma and the New Deal," in The New Deal, Vol. 2, The State and Local Levels, ed. John Braeman, Robert H. Bremner, and David Brody (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1975).

John Joseph Mathews, Life and Death of an Oilman: The Career of E. W. Marland (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1951).

Anne Hodges Morgan and H. Wayne Morgan, eds., Oklahoma: New Views of the Forty-Sixth State (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1982).

James R. Scales and Danney Goble, Oklahoma Politics: A History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1982).

Donald Worster, Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979).

Related Resources

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Keith L. Bryant, Jr., “New Deal,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=NE007.

Published January 15, 2010

© Oklahoma Historical Society