HIGHWAYS.

Throughout the twentieth century good roads, highways, and bridges have facilitated economic development by connecting rural dwellers to urban areas, communities to other communities, and states to other states. The need for a transcontinental road across the nation had developed as early as the mid-nineteenth century, prompting the U.S. Army to send Lt. Amiel W. Whipple and Col. Randolph B. Marcy with expeditions to survey routes across future Oklahoma. In 1858–59 Edward F. Beale blazed a wagon road from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to California. He mapped out a route along the main (South) Canadian River and constructed bridges across the Sans Bois and Little rivers. Later, portions of State Highways 31, 59, and 37 replicated this pathway. Travelers could also follow other well-known routes such as the Western Trail, the Chisholm Trail, and the Shawnee Trail (Texas Road), or military routes established by the U.S. Army to connect forts and cantonments, particularly Forts Gibson and Towson in the eastern part of the Indian Territory, and Forts Elliott (in Texas), Supply, Reno, and Sill in the west. The southern section of the Butterfield Overland Mail and Stage route through the Choctaw Nation also facilitated cross-country traffic.

Transportation facilities, minimal in territorial Oklahoma, began to develop in the two decades after statehood. Roads and trails such as Beale's that had facilitated travel in the 1800s by 1900 might lie across someone's farm or ranch, and not all landowners allowed passage. In the early years of statehood rural roads followed land-survey section lines, a design that required travelers to zigzag constantly, going a mile east or west and then a mile north or south, to get from place to place. In the early years of statehood county commissioners were generally responsible for grading and maintaining the section-line roads. Because school districts consolidated, requiring busing of students from their farm homes to rural or urban schools, local officials often needed to improve roads.

Due in part to a nationwide and statewide good-roads movement, an Oklahoma state Highway Department was created in 1907 and began to function in 1911. Unfortunately, it had neither an appropriation nor a construction-maintenance mandate. The first commissioner, Sidney Suggs, envisioned six highways traversing the state. Five would run north and south, from Kansas to Texas, and one would extend from Muskogee through Oklahoma City to the Texas Panhandle. By 1914 the newly planned state highway system proposed twenty-four hundred miles of roadways.

As the Automobile Age progressed, the number of cars and trucks in the state grew from 15,000 in 1914 to 127,000 in 1918 to 500,000 in 1926. The activity of good-roads promoters, chambers of commerce, and legions of automobile owners and tourists ensured the development of intrastate and interstate thoroughfares. While state officials discussed methods of facilitating highway construction and worried about funding, private citizens agitated and organized to promote both state and federal action.

On a national scale, growing automobile tourism and the trucking industry needed well-marked, paved roads leading from state to state. Thirteen transcontinental highways were proposed, exemplary of which was the Lincoln Highway from New York to San Francisco via Philadelphia, Omaha, Denver, and Salt Lake City. Leadership in the movement was taken by Logan W. Page, head of the U.S. Office of Public Roads, and Sen. John H. Bankhead of Alabama, chair of the Committee on Post Offices and Post Roads.

In Oklahoma as well, citizens banded together, mapped out likely routes, and publicized their efforts in order to create a groundswell of public support. They also tried to secure federal and state designation for the routes. The Oklahoma Good Roads Association, under Suggs and later under Cyrus Avery of Tulsa, provided leadership, and from 1914 through 1918 it and other organizations promoted "named" highways crossing Oklahoma and connecting it to adjacent states. Cities and towns often vied for inclusion on the routes. Proposed north-south highways included the Ozark Trail, the Jefferson, the Kansas-Oklahoma-Texas (K-O-T), the Dallas-Canadian-Denver (D-C-D), the Meridian, and the Star. East-west highways included the Albert Pike, the Postal, and the Lee-Bankhead. After securing support from local chambers of commerce and county officials, if not always from state officials, advocates would place signs or concrete markers to guide travelers along the way, which often proceeded along the rough, occasionally impassable section-line roads.

A state highway system remained an unrealized dream until the U.S. Congress passed the Federal Aid Road Act in 1916. It provided one-to-one matching grants to states for roadways, bridges, and other structures on state highways that were considered eligible for inclusion in a nascent Oklahoma Federal Aid System. The law also required that each state have a legitimate, well-funded, professionally managed highway department. By 1919 Oklahoma's legislature had appropriated funds to secure the federal match, and in September 1923 the U.S. secretary of agriculture approved Federal Aid Highways in Oklahoma. In 1923 the legislature passed a one-cent-per-gallon tax on gasoline, becoming the thirty-eighth state to do so. The Highway Department and the counties shared in the revenue fund for construction and maintenance, but it proved not nearly enough. The tax was raised to 2.5 cents in 1924. In August 1924 the Ninth Legislature passed Senate Bill 44, creating the State Highway System, under the management of a three-member Highway Commission, and defined three kinds of roads: state highways, county highways, and township roads. The state system was to comprise intercounty and interstate highways and was to total at least five percent of the each county's roadways. The state and county roads were eligible for federal and state funds.

The commission designated state highways and numbered them 1 through 26. State Highway 2, the Meridian Highway, extended from Caldwell, Kansas, through Medford, Pond Creek, Enid, Kingfisher, El Reno, Chickasha, Marlow, Duncan, and Waurika to the Red River. The Jefferson Highway, designated as State Highway 6, extended from Chetopa, Kansas, through Vinita, Pryor, Wagoner, Muskogee, Checotah, Eufaula, McAlester, Atoka, and Durant to the Red River. State Highway 7, earlier promoted as the Ozark Trail, linked Baxter Springs, Kansas, Miami, Afton, Vinita, Claremore, Tulsa, Sapulpa, Bristow, Stroud, Chandler, Davenport, Oklahoma City, Newcastle, Chickasha, Lawton, and Altus. State Highway 4, the K-O-T, stretched from Newkirk through Ponca City, Perry, Guthrie, Oklahoma City, Norman, Ardmore, and Marietta to the Red River. East-west arteries included State Highway 11, the Albert Pike Highway, linking Siloam Springs, Kansas, Locust Grove, Chouteau, Tulsa, Skiatook, Pawhuska, Ponca City, Pond Creek, Cherokee, Alva, Buffalo, Hooker, and Boise City. State Highway 3, the Postal Highway, extended from Fort Smith through Poteau, Wilburton, McAlester, Holdenville, Wewoka, Shawnee, Oklahoma City, El Reno, Weatherford, Elk City, and Sayre, into Texas. State Highway 5, the Lee-Bankhead Highway, a transcontinental road, stretched from Ultima Thule, Arkansas, through Idabel, Hugo, Durant, Ardmore, and Waurika to Frederick and crossed the Red River at Davidson. All were completed by 1925, and in that year the state system comprised approximately five thousand miles, of which approximately three hundred were paved.

By the end of 1924, 194 federal aid projects had been approved for Oklahoma, and the state had completed 73 projects in forty-seven counties at a cost of $20,203,354. This included constructing 790 miles of roadway. Oklahoma's Federal Aid Project Number One, the ten-span, two-thousand-foot-long Newcastle Bridge across the Canadian River in Cleveland County, was funded in 1919 and completed in 1923, providing a much needed crossing of that waterway. Number Three, completed in 1919, was a two-mile experimental project on East Twenty-third Street in Oklahoma City to test the comparative durability of brick, asphalt, and concrete surfacing.

In 1925 Cyrus Avery of Tulsa, one of the three commissioners, was tapped to serve on a new federal Joint Board of Interstate Highways to design a national highway system. The American Association of State Highway Officials approved their work in November 1926, and thereafter all forty-eight states adopted uniform federal highway numbering. For Oklahoma the federal government designated nine U.S. interstate highways totaling 2,120 miles. Their numbers were U.S. 66 (roughly, State Highway 7, still 66), U.S. 64 (roughly, State Highway 1, still 64), U.S. 266 (eastern part of original State Highway 9), U.S. 70 (roughly, original State Highway 5, the Lee-Bankhead, still 70), U.S. 73 (the Jefferson Highway, generally the route of the Texas Road/Shawnee Trail and original State Highway 6, redesignated U.S. 69 in the 1930s), U.S. 75 (designated portion was part of original State Highway 12, still 75), U.S. 77 (the K-O-T, original State Highway 4), U.S. 81 (the Meridian Highway, original State Highway 2, still 81), and U.S. 271 (parts of original State Highways 23 and 3). When its paving was completed in November 1930, U.S. 77 became the state's first border-to-border, hard-surfaced highway.

After World War II the Oklahoma public began buying automobiles and traveling in record numbers. Unfortunately, even by 1955, only 20 percent of the state's highways had paved surfaces. Economic expansion was fueled by a boom in petroleum drilling and production and an increased federal defense presence. Tulsa and Oklahoma City businessmen encouraged state officials to think in terms of expanding the highway system, this time using the concept of toll roads as a means to overcome the need to spend state-appropriated funds for construction and maintenance.

Tolls have been part of Oklahoma transportation history since the early nineteenth century. The Indian nations empowered their citizens to build turnpikes and toll bridges, and the tradition continued into the statehood era. The state allowed private companies to construct toll bridges across creeks and major waterways. This cost-effective method resulted in many bridges and facilitated travel. Nevertheless, citizens resented paying, and toll bridges became an issue in the 1928 election. Legislators responded with new laws, and by 1936 numerous private bridges on state highways were owned by the public, even though seven toll bridges still operated.

The toll idea assumed a new currency during World War II. After the war, in April 1947, at the behest of Gov. Roy J. Turner, the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority (OTA) came into being. The first members of the commission were the governor (Turner), J. Wiley Richardson of Oklahoma City, Joe R. Jarboe of Tulsa, Paul Wilson of Stroud, and R. P. Matthews of Sapulpa. The commission was authorized to issue bonds, construct, operate and maintain the highway, and return it to the Highway Commission when its cost was recouped. As a result, the Turner Turnpike, which generally parallels U.S. 66 between the two cities, opened in spring 1953.

Revenues generated by the Turner Turnpike proved that a road could be self-sustaining. Subsequently, others opened in the next two decades. The major ones included the Will Rogers Turnpike between Tulsa and Miami (1957), the H. E. Bailey Turnpike, from Oklahoma City through Lawton to the Red River (1964), and the Indian Nations Turnpike, from Hugo north to Henryetta (1966). In the 1990s four new pay roads opened, including the John Kilpatrick Turnpike across northern Oklahoma City (1991 and 2001) and the Creek Turnpike, passing through eastern Tulsa (1992). In 2001 OTA operated ten turnpikes comprising 612 miles.

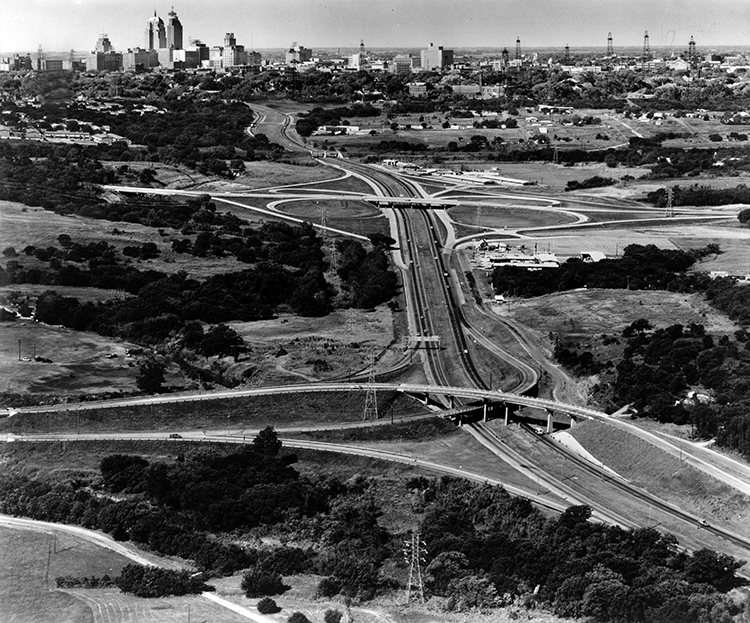

During World War II national defense programs grew to include plans for a system of superhighways. They were needed to facilitate rapid movement of military supplies and soldiers around the nation in event of a crisis. Federal Aid Highway Act of 1944 created a system of Interstate Highways, and in 1947 routes were approved by the Defense Department. Funding came in highway acts in 1952 and 1956, the motivating force of the latter having been Pres. Dwight D. Eisenhower. Forty-one thousand miles were designated as the Interstate Highway System. Interstate 35 was constructed paralleling the route of U.S. 77 north and south, and Interstate 40 was constructed paralleling the original route of State Highways 3 and 9 east and west. They intersected in Oklahoma City, and each also crossed Interstate 44, of which the Turner and Bailey turnpikes were a part. With the exception of I-44 through Oklahoma City, completed in 1985, the Oklahoma segment of the interstate system was in place by 1975.

At the end of the twentieth century Oklahoma's highways included 930 miles of interstates, of which 260 were turnpikes. This comprised 2 percent of the nation's interstate mileage, and only New York maintained a larger toll road system. Oklahoma's other federal highways totaled 2,392 miles. The rest of the state highway system (some still unpaved) totaled 11,599 miles.

See Also

AIRPORTS, RAILROADS, STEAMBOATS AND LANDINGS, TRANSPORTATION

Bibliography

William P. Corbett, "Men, Mud, and Mules: The Good Roads Movement in Oklahoma, 1900–1910," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 58 (Summer 1980).

William P. Corbett, "Oklahoma Highways: Indian Trails to Urban Expressways" (Ph.D. diss, Oklahoma State University 1982).

"Highways," Vertical File, Research Division, Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma City.

Joseph E. King, Spans of Time: Oklahoma's Historic Highway Bridges (Lubbock, Tex.: Center for Historic Preservation and Technology, 1993).

Report of the State Highway Commission of Oklahoma for the Years 1919 to 1924 Inclusive (Oklahoma City: January 1925).

Report of the State Highway Commission of Oklahoma for the Years 1925 to 1926 Inclusive (Oklahoma City: 1927).

Lonn Taylor, "Red River Bridge Controversy," The New Handbook of Texas, ed. Ron Tyler (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1995

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Dianna Everett, “Highways,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=HI004.

Published January 15, 2010

© Oklahoma Historical Society