Cows and Cowhands

Printable Version

Feeding the growing northeastern cities became increasingly difficult during the 1800s. With little room to maintain cattle within city limits or nearby, the long drive emerged as a way to feed everyone. The long drive began in Texas, where cattle would roam freely. Cowboys, or drovers, needed to escort, or drive, cattle over 600 miles to railroads in Kansas. Railroads began to expand into the interior parts of the country during the growth of industrialization, creating the foundation for a push towards an integrated national food market. Western lands offered more space for cattle and crops than the Northeast. In Texas and Indian Territory, cattle sold at low prices. If drivers could transport the cattle to Kansas or Missouri, the price would increase considerably. From the 1860s to 1890s, groups of twelve to fifteen men transported herds of cattle to railheads in Kansas. From there, railcars transported cattle to slaughterhouses in large eastern and midwestern cities. The journey could take fifteen men up to three months to move a typical herd of 2,500 head of cattle to the railroads. The work of driving cattle was incredibly difficult and exhausting. Those who worked in this industry came to this work for a variety of reasons. As cowboys, they found a work culture with strong traditions and high expectations. This work culture soon moved beyond the industry and influenced many other aspects of American life, such as live entertainment, sports, and movies.

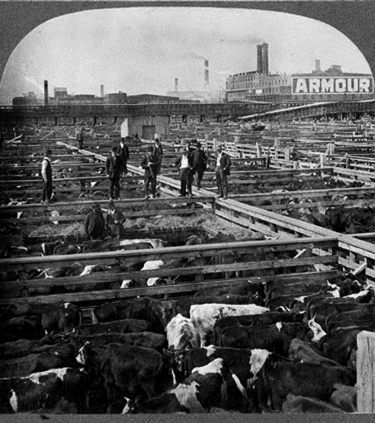

The Great Union Stock Yards, Chicago (courtesy of the Library of Congress).

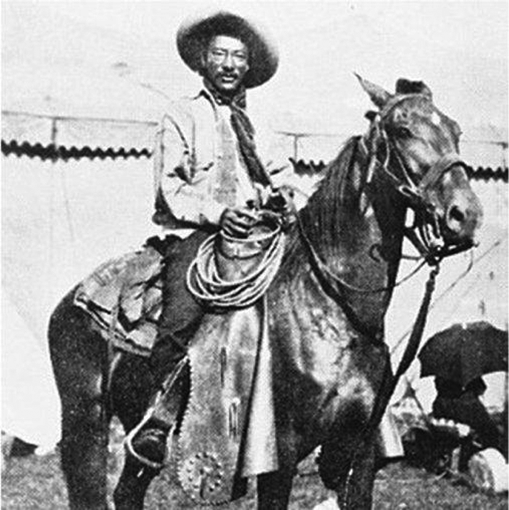

Bill Pickett, legendary cowboy and entertainer (image courtesy Huffington Post).

These trail crews were among the most diverse workforces in the United States during the 1800s. The crews were often made up of any combination of white, African American, Mexican, Tejano, or American Indian drovers. With an average age of 24 years, these men came from all walks of life and would often spend long periods of time away from their families. Some came from families without means and were forced to go out into the world on their own. Others were leaving the difficult conditions in the South following the Civil War. Many non-white riders faced tremendous discrimination in other walks of life.

Texas longhorn, photo by Jim Argo, June 26, 2000 (23389.346.55, Jim Argo Collection, OHS).

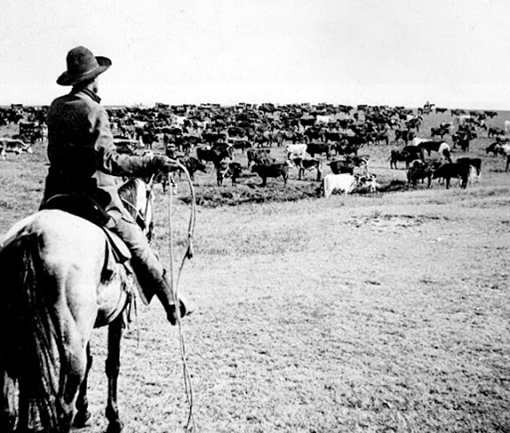

Cowhands in Texas (image courtesy King Ranch).

These trail riders were not the only ones on the drives. Horses, to this day, are deeply connected to the modern cowboy; however, on the trails, riders did not own a specific horse. Horses were expensive to purchase and maintain. For that reason, the majority of the horses used on drives actually belonged to the person who owned the cattle. Also, a rider who owned their horse could easily abandon the drive and leave the trail boss short-handed. The remuda would follow alongside the drive and serve as substitutes for the riders when their horse would get tired. The remuda, the Spanish word for exchange, also serves as a reminder of the Mexican vaquero origins of these large cattle drives. At the completion of the drive, the rider was usually paid and could purchase their favored horse.

During breaks, the drovers corralled the remuda behind a rope fence (image courtesy University of North Texas Libraries).

Drover and horse (image courtesy Texas State Historical Association).