Cows and Cowhands

African Americans and the Cattle Industry

African Americans comprised up to 25 percent of those employed by the cattle industry. Factors like experience in kitchens and with livestock during enslavement contributed to their presence, as did the fact that working cattle drives was hard, undesirable work.

During the early nineteenth century, many enslaved African Americans of the Five Tribes traveled to Indian Territory on the Trail of Tears. They contributed to the development of the large-scale ranching operations members of the Five Tribes built prior to the Civil War. Since 1819, white slaveholders moved into what would become Texas and set up ranching operations. African Americans quickly picked up roping and horseback riding skills. During the Civil War, many slaveholders left to fight for the Confederacy and the enslaved African Americans were left behind to tend to the ranching operations. Following the Civil War, African Americans in the West could move with more freedom. Some of these individuals took this experience and began working on ranches and cattle drives for wages.

Black cowboys participated in all aspects of the long drive. Being a cowhand was not an easy task, and not everyone could keep up; however, cattle driving would prove to be far more profitable than sharecropping, which was largely the only occupation for Freedmen in the south during the Jim Crow era. In contrast, Black cowboys were paid the same as white cowboys as opposed to Mexican vaqueros and Tejanos, who made approximately a third less. Hierarchies often were more influential during the drive than race. Wranglers, often young teens, held the lowest status while the cowboys, regardless of race, would ride drag in the rear of the herd because of their lack of experience. Cooks regularly held the highest status among the riders except for the trail boss. As a Black cook, one could have a significant say about disputes or other matters that may arise on during the drive. Along with the additional respect, cooks also received a significantly higher wage. Unfortunately, race still heavily impacted life on the range, and there is little evidence of Black men obtaining the position of trail boss.

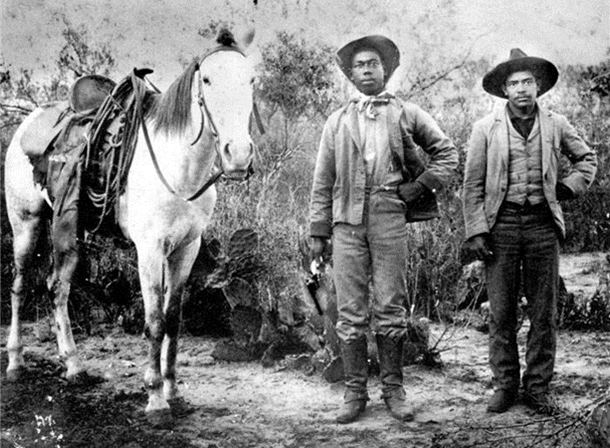

Cowboys, c. 1900 (image courtesy of the University of Texas at San Antonio Libraries Special Collections).

This had nothing to do with skill. It was because the trail boss needed respect from the crew and other individuals throughout the route. Black men in positions of authority were not guaranteed respect from whites. Cattle owners were reluctant to hire a Black trail boss because of their unequal social standing of the day. The towns along the cattle trail were segregated. Many bars had separate entrances based on race but would often allow for intermingling in “neutral points.” Restaurants would refuse service but would allow for take-out orders. The situation was heightened if white women lived in the town in which the drovers stopped.

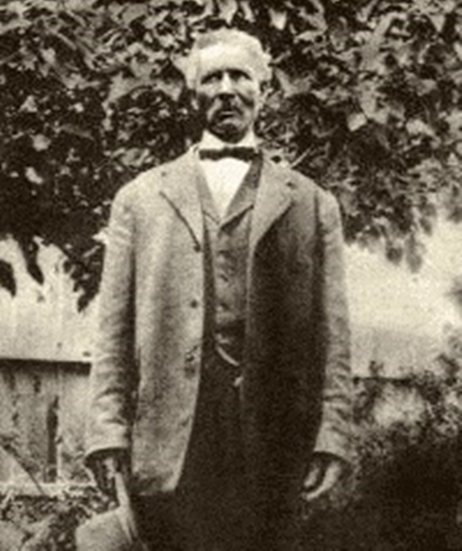

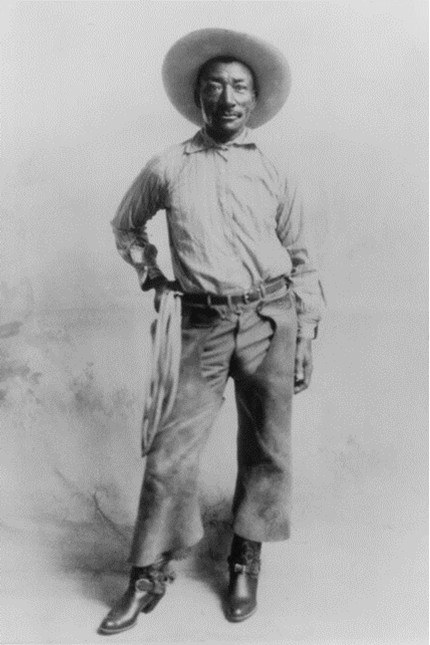

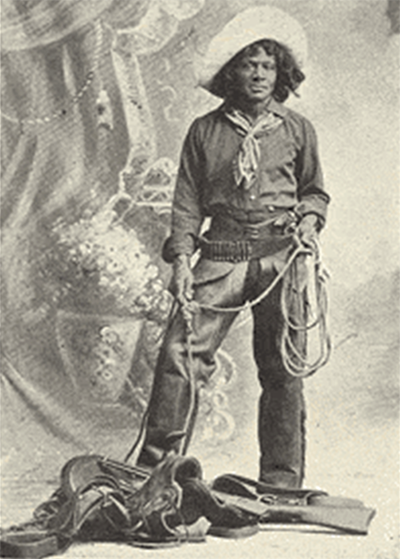

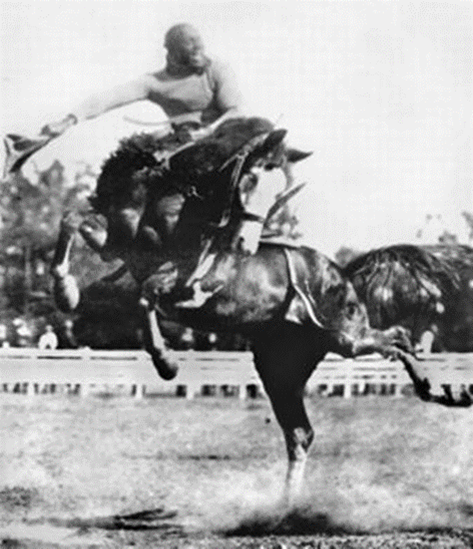

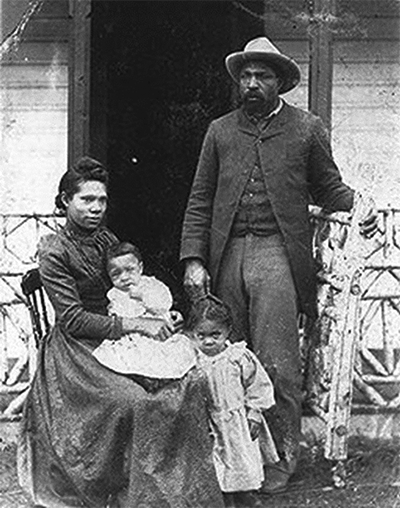

There are many well known Black cowboys and ranchers. Bose Ikard was born enslaved in Mississippi but found work with Charles Goodnight for many years after the Civil War. Goodnight said that he “trusted Ikard that any living man.” Nat Love became famous in Deadwood, South Dakota, after easily winning a rodeo. He wrote a famous memoir titled, The Life and Adventures of Nat Love. Born enslaved in South Carolina, John Ware came west. After working as a drover, he became one of the wealthiest ranchers in Alberta, Canada. Johanna July was a Black Seminole who became a renowned horse trainer. Jesse Stahl was a famous rodeo performer while Bill Pickett worked as both a rodeo performer and a rancher. Bill Pickett would become the first Black man to be inducted into the Rodeo Hall of Fame.

Bose Ikard (image courtesy PBS).

Bill Pickett, c. 1902 (image courtesy North Fort Worth Historical Society).

Nat Love, aka Deadwood Dick (image courtesy PBS).

Johanna July (image courtesy Texas State Historical Association).

Jesse Stahl (image courtesy BlackPast).

John Ware with his wife Mildred and their two of their eight children (image courtesy Library and Archives Canada).