Cows and Cowhands

Preparing for the Ride

Drovers would earn about $100 (roughly equivalent to just under $3,000 in today’s money) per trip in addition to the free food provided by the trail cook. The trail boss and cook earned more, but the average hand would make about $1 a day. Initial expenses for the rider included work clothes, such as underwear, socks, shirt, ban-dana, vest, and pants. A pair of boots would be an additional $3.75, and a new hat cost $3. While spurs were only $0.50, chaps could be as much as $8. Lastly, the saddle, one of the most important pieces of equipment for cattle driving, was usually the most expensive piece at $30. Luckily for the drovers, items like chaps, boots, and spurs could last a few years. The saddle could last a lifetime with proper maintenance and care.

A basic saddle for working (image courtesy American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming).

Life on the Open Range

During the drive, a trail rider had to cross much of Texas, the entire Indian Territory, and part of Kansas. However, there were a few instances where they would go even further. Throughout the journey, they faced physical and mental exhaustion, loneliness, isolation, and were exposed to nature with little to no protection. With such conditions, it is no surprise that some trail riders gave up and ran away.

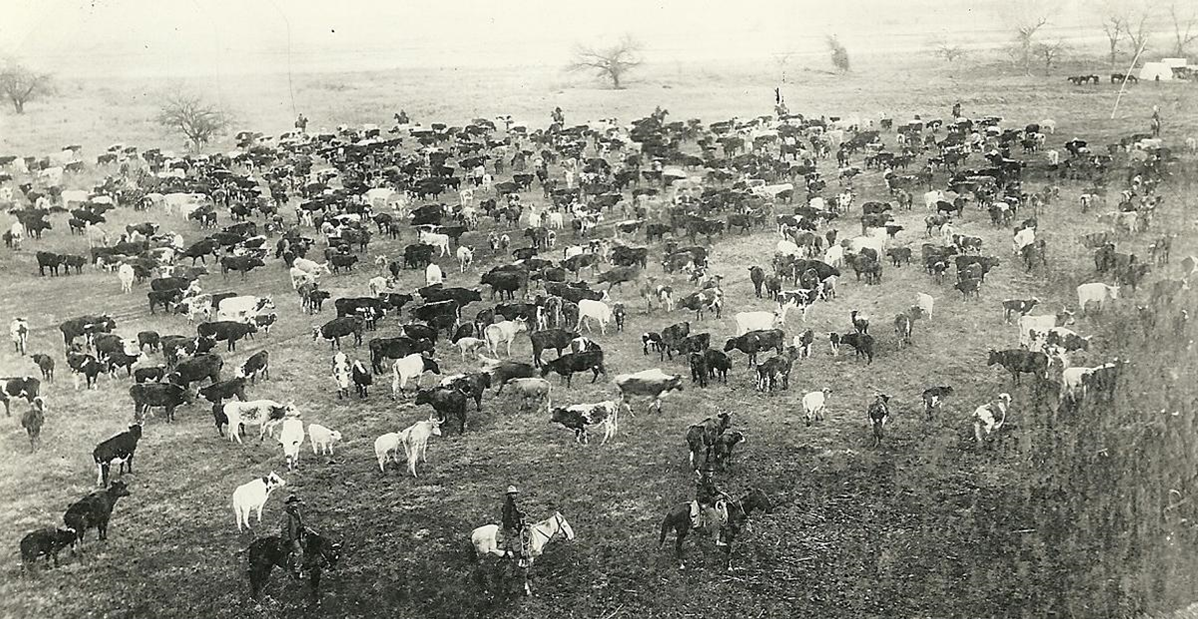

Cows and cowhands on the Western Trail (image courtesy Dodge City Daily Globe).

Cattle branding (image courtesy ND.gov).

Stampedes were dangerous and feared by everyone in the crew. Stampedes could happen anytime and without warning. Horses and cattle can weigh up to two thousand pounds and easily cause devastating damage to riders and other animals. With over two thousand head of cattle, a stampede could become deadly very quickly. Anything from a snake startling a calf to rustlers attempting to steal cattle during the night could start a stampede. Rustlers would use stampedes as opportunities to run off with as many cattle as they could handle. A couple of riders would stand guard overnight, but even they could not be at all places at once, especially when guarding so many heads of cattle.

River crossings are not naturally dangerous, but during the springtime, rivers swell up and contribute to cattle drowning, or turning back. With deep and wide rivers, the cattle would exhaust themselves, and they

might turn around or drown. Turning around would lead to a backup and cause more cattle to tire, worsening the problem. The movement of so many heavy animals in a short time and space caused serious softening of the wet riverbanks, causing the banks to become unstable. This led to injuries for the animals because they were unable to find solid land and move out of the river.

Cattle crossing a river at night (image courtesy Wyoming Tales and Trails).

Even before daybreak, the cook would be busy preparing breakfast for the crew. With haste, the riders had to get dressed and prepare to go. Riders would get positioned relative to the herd to protect it from any possible threats. Around noon, everyone would stop for lunch. The riders took turns eating so that the herd would not be left un-attended at any point. The herd and riders would cover around 12 to 15 miles every day. The trail boss limited the distance traveled to allow the cattle to gain weight as they grazed along the drive. As the evening approached, the trail boss would have already found a location to set up camp for the night. The ideal campsite would have plenty of grass and a water source for the cattle.

Trail cooks got little sleep on the drive (image courtesy True West magazine).

Cowboys gather for a photo after a meal (image courtesy True West magazine).