Latino History in Oklahoma

1980–2020

Demographic Change

The size of the Latino community in Oklahoma steadily increased from the post-Depression low of 1,425 in 1940. The 1980 census indicated there were 57,419 Hispanic Oklahomans. Estimates for 2018 suggest the number has grown to 429,000. The percentage of the total state population that is Latino has grown from 1.8 percent in 1980 to approximately 10.8 percent in 2018. The median age in Oklahoma is 36, while the median age for Latinos in Oklahoma the age is 23. This indicates that the Latino population is much younger than the overall population. There are large communities in both Oklahoma City and Tulsa, but a major source of growth is in more rural communities such as Guymon and Watonga, where the populations are majority Latino and exceed (as a percentage of the population) that of the two largest cities. The population increases are mostly because of movement of Latinos from other states to Oklahoma and higher birth rates. A third of the state’s Latinos are foreign-born, and a percentage of these individuals, perhaps a third, are undocumented. Asylum-seekers from Central American countries are a recent addition to Oklahoma’s Latino foreign-born population.

Jesus Ruiz is a barber in Guymon, Oklahoma (image courtesy of Reuters).

Ramiro Vasquez opened La Oaxaquena Bakery on SW 29th Street in Oklahoma City in 2009, joining dozens of other Latino-owned businesses (image courtesy of The Oklahoman).

Changes in Immigration Law

While the 1965 immigration law remains the foundation of immigration law and policy in the United States, there have been some major changes in the law that impacted the foreign-born portion of the Latino community in the state. In 1986, during the Reagan Administration, the Immigration Reform and Control Act became law. This law combined punitive measures toward individuals attempting to enter the country without authorization and those hiring them, with an opportunity for those already living in the United States to normalize their status. This was commonly known as “amnesty.” Because Oklahoma was home to a sizeable undocumented population in the 1970s, many in the state applied for a Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR or green) card under this provision. With 20,000 applicants, Oklahoma ranked in the top ten of states. This allowed many individuals the opportunity to sponsor other family members once they attained citizenship.

Ten years later, President Bill Clinton signed into law the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA). This law included several parts. The elements with the strongest impact on Oklahomans were the strengthening of border security at the US-Mexico border and bans on re-entry for people living in the US without authorization who left the country. These changes helped make migration to the US much more one-way and permanent. In the years before this law, when movement across the border easier, many people might live and work in the US for some time and then return to their country of origin. At the time of the passage of the law, most of the undocumented immigrants in the country had lived in the US for more than ten years. They usually belonged to mixed-status families. The hard border and strong punishments for being caught meant fewer undocumented immigrants would take the risk of crossing the border again because they would be separated from their families. The number of undocumented individuals living in the United States nearly tripled ten years after the passage of IIRIRA.

Three members of the Rendon family faced deportation until the Immigration Control and Reform Act passed in 1986; photo by Jim Beckel (2012.201.B1083.0558; Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

In 2012, President Barack Obama signed an executive order known as DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) to address the challenges facing “Dreamers.” A specific category of undocumented immigrant, Dreamers came to the US as children. Not all Dreamers are Latino but many of the Dreamers in Oklahoma are. DACA provided eligible Dreamers with permission to work and protection from deportation. In Oklahoma, nearly 10,000 individuals were eligible. Approximately 7,000 participate in the program.

Oklahoma “Dreamers” advocate for a legislative solution for childhood arrivals in 2017. DACA was an executive order rather than a law (image courtesy The Oklahoman).

Wider Community

Institutions and individuals beyond the Latino communities in the state responded to the identifiable increase in the Latino population. Some groups, organizations, and institutions adapted their services and sought strategies to bridge language gaps. Others, viewing the rapid growth of these communities, worked to create barriers to services and limit further growth. Latino communities in Oklahoma offered support and guidance on inclusive efforts. Latino leaders and community members met efforts to create policies that excluded immigrants or Spanish-speakers with protest.

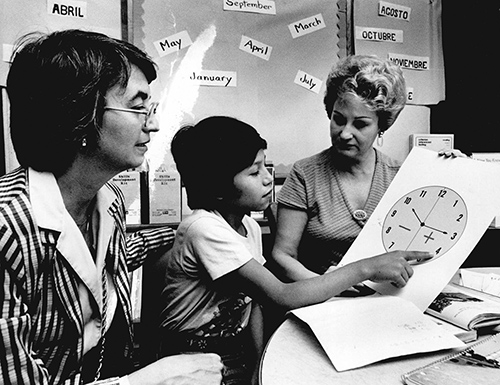

Libraries within neighborhoods with a large number of Spanish speakers began working on increasing the Spanish language material and programming available. Schools reworked their bilingual programs. Most large school districts offered some kind of bilingual education in the 1970s in response to federal funding requirements and a large number of students who spoke only Vietnamese or Spanish enrolling in schools. A bilingual educator, Rosa Alvarez, saw the need for more trained teachers in bilingual education and pursued hundreds of grants to fund this education. By the 1990s, these programs grew both in size and across the state as the Spanish-speaking population in Oklahoma rapidly increased and settled in new communities. By the 2000s, most bilingual programs offered a model that includes intensive instruction in English for part of the day and sheltered instruction in other subjects for the rest of the school day. Businesses employing large numbers of Spanish-speakers sought advice and bilingual speakers to improve workplace safety and efficiency.

Politically, until 2007, the general approach toward Latino communities in the state was inclusive. In 1996, Governor Frank Keating established the Governor’s Advisory Council on Latin American and Hispanic Affairs. It was not abolished until 2011. A law in 2001 made the state driver’s license test available in multiple languages. In 2003, State Representative Kevin Calvey introduced legislation making undocumented immigrants eligible for in-state tuition, financial aid, and scholarships. This became law, and only three other states offered such expansive educational benefits for undocumented immigrants. These measures proved popular in Latino communities that included some monolingual Spanish speakers and undocumented members.

Bilingual instruction in 1980 (2012.201.B1329.0325, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

Tulsan Yolanda Charney served on the Governor’s Advisory Council on Latin American and Hispanic Affairs (image courtesy ¡Latino Presentes!).

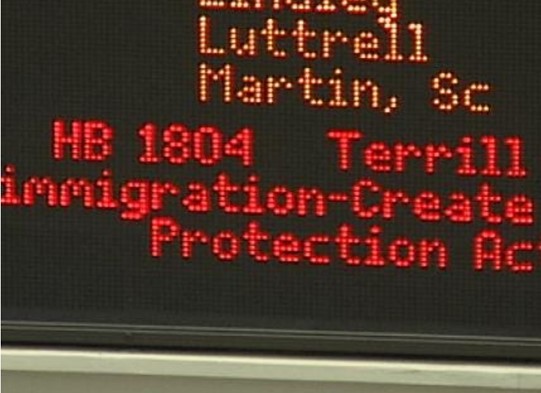

English Only and HB1804

In 2003, efforts to pass an English-only bill failed, but the bill marked the beginning of a strong effort seeking legislative goals to create barriers for Spanish-only speakers and undocumented immigrants, both groups making up a portion of the Latino communities in Oklahoma. In 2006, state representative Kevin Calvey attempted to pass a bill that required state employees to make reports to immigration authorities if a client could not prove their status. In 2007, the Oklahoma Legislature passed state representative Randy Terrill’s HB1804 bill, and Governor Brad Henry signed it into law. HB1804, also known as the Oklahoma Taxpayer and Citizen Protection Act, sought to do several things. First, it carried explicit punishment for employers of undocumented immigrants, although this provision was later set-aside. It also confirmed that undocumented immigrants were ineligible for several benefit programs and slightly extended the number of programs these individuals were barred from accessing. They were also barred from official state-created forms of identification, such as driver’s licenses. HB1804 encouraged local law enforcement to participate in programs allowing them to enforce federal immigration law. At the time of its passage, the Oklahoma Taxpayer and Citizen Protection Act was considered the harshest anti-immigrant state law in force. This law provoked fear and protest from Latino communities in Oklahoma. In response to its passage, some mixed-status Latino families left the state. In 2010, State Question 751, or “English-only” law, made it to the November ballot. Voters approved the question with 75 percent in favor, adding a law requiring most official state business be conducted in English. A Tulsa attorney challenged the law based on the First Amendment, but the case was thrown on other grounds.

HB1804 comes up for a vote (image courtesy of News on 6.)

Protest

Efforts to create barriers for Spanish-only speakers and undocumented immigrants were opposed by significant numbers within Latino communities in the state. In 2006, as harsh anti-immigrant measures were introduced in both Congress and in the Oklahoma Legislature, large protests took place in Oklahoma. The Governor’s Advisory Commission on Latin America and Hispanic Affairs wrote a letter to legislators encouraging them to oppose the bills. LULAC held a rally to protest these bills. On April 1, 10,000 Oklahomans, including a large number of Latino Oklahomans, converged on the Capitol to demand immigration reform that did not criminalize immigrants. Nationwide protests called “A Day Without an Immigrant” took place in May 2006 and large numbers of Latino Oklahomans participated, with a youth-led march through Capitol Hill in Oklahoma City, 1,500 protestors in Tulsa, and 200 protestors at the Guymon County courthouse. Some employers closed their businesses so their employees could participate.

The Oklahoma Capitol on April 1, 2006. Photo by John Clanton (image courtesy of The Oklahoman).

Dreamers organized their own protests and support organizations. In 2009, organizers established Dream Action Oklahoma (now DAOK). This group began by assisting Oklahoma Dreamers with assistance filling out the DACA application and scholarships for Dreamers unable to afford the $500 filing fee. They also conducted Know Your Rights clinics and made speakers available for community events. Dream Action Oklahoma also advocated for passage of the 2001 Dream Act, which would have offered a pathway to citizenship. The organization also staged numerous protests in support of “Dreamers” including vigils and marches. In 2012, Judith Huerta publically announced her undocumented status at her college graduation wearing “UndOCUmented” on her robes. At other graduations, Dream Action Oklahoma dropped banners reminding the participants that there were undocumented students among them at the event. Since 2017, DAOK has organized students in walkouts to support DACA, which drew hundreds of participants. They have organized protests against the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency.

Santa Fe South walkout, November 8, 2019 (image courtesy of Oklahoma City Free Press).

Building Communities

Guatemalans

The Guatemalan community in Oklahoma rapidly expanded in size and geography in the 1990s. Original families in Oklahoma often found success and sponsored other, extended family members. Certain surnames are closely connected to these early families, such as Cifuentes, Barrios, De Leon, Lopez, and Gramajo. The majority of Guatemalans in Oklahoma are from the western region of Guatemala, primarily the municipality of Sibilia in the town of Quetzaltenango, followed by individuals from the town of San Marcos, Guatemala. Maya culture and tradition are dominant in this region; in fact, Spanish is no longer the primary language of many Guatemalans in this region. Instead, they speak a variety of indigenous languages.

This community is now the second-largest Latino community in Oklahoma with a population over 25,000. The large number of Guatemalans in Oklahoma and surrounding states influenced the Guatemalan government to open a consulate in Oklahoma City in 2017, so these individuals would not have to travel to Houston for consular services. In addition to assistance with documents, Ambassador Jose Arturo Rodriguez Diaz and his staff work to increase awareness and understanding of Guatemala and its relationship with Oklahoma.

Guatemalan ambassador, Jose Arturo Rodriguez Diaz, and wife, Jennifer Rodriguez (image courtesy of The Oklahoman).

Pastor Saidy Herrera de Orellana leads a church in Norman (image courtesy Saidy Orellana).

Jerry Gramajo Cifuentes, “Dreamer” and Mr. Guatemala 2019–2020 (image courtesy of El Nacional).

Hilda De Leon Xavier, traditional dance instructor and community leader (image courtesy of una-okc.org).

Puerto Ricans

Military bases in Oklahoma continued to serve as a magnet for Puerto Rican communities. One long-time Puerto Rican resident of Oklahoma, Lino “Taino” Roldan, learned how to operate radio equipment in the military. In retirement, he began a popular internet radio program named Radio La Brisa Tropical. He also founded the Puerto Rican Foundation of Oklahoma in 2012. This program and organization offer Puerto Ricans a way to share their culture, celebrate together, and help students through scholarships. Some Oklahoma businesses and school districts viewed Puerto Rico as a promising place to recruit bilingual workers. Advance Foods in Enid offered cash bonuses and free airfare to relocate to Oklahoma and work in their meatpacking plant. Due to the large Latino population, Oklahoma City Public Schools began a campaign in 2014 to hire Puerto Rican teachers in the district.

Lino “Taino” Roldan (image courtesy of El Nacional Oklahoma).

The island of Puerto Rico experienced severe financial problems that, while beginning in the 1990s, did not become a major problem until the early 2010s. In 2017, the government of Puerto Rico defaulted on their debts, meaning they announced they were unable to pay back money they borrowed. This hurt the people living on the island in a number of ways. Some people lost their jobs while others lost their retirement investments. The services offered by the government were drastically reduced so it became more difficult to live on the island. Then, beginning in 2017, two devastating hurricanes hit the island. This resulted in many Puerto Ricans looking for op-portunity in the mainland of the United States. The Puerto Rican community in Oklahoma continues to grow.

Teachers from Puerto Rico arriving to work in Oklahoma City Public Schools (image courtesy of KFOR.com).

South American Communities

The oil company CITGO, once one of the largest oil companies in the world, relocated its headquarters to Tulsa in 1964. After the extremely uneven oil markets in the 1970s, CITGO looked for investment capital. In 1986, the state oil company of Venezuela, PDVSA, purchased 50 percent ownership in CITGO. In 1990, they took full ownership. The ties between PDVSA and CITGO meant a large number of Venezuelan employees and their families visited or moved to Tulsa. This laid the foundation for the Venezuelan community in Oklahoma. Within the last few years, instability in Venezuela spurred new migrations from the country.

Universities also attracted South Americans. At the University of Oklahoma (OU), both Bolivian Millie Audas and Colombian Yoana Walschap worked to cultivate the connections between South America and Oklahoma. Dr. Audas served as the director of International Student Services for many years. In that role, she created agreements with other universities around the world but many in South America, to make it easier for their students to study at OU more easily and at a lower cost. Yoana Walschap spent part of her academic career as the director of the Energy Institute of the Americans. Through this position, she built connections and agreements that resulted in many students from all over South America attended the University of Oklahoma for part or all of their degree programs. Her efforts directed at fellow Colombians helped build a strong community both here and in Houston. Both she and Dr. Audas innovated programs and mentored South American students that assisted them with living in a new country and state.

Dr. Millie Audas (image courtesy of The Oklahoman).

Yoana Walschap (image courtesy of the Smile Education Foundation).

Students participating in the OU Cousins program developed by Dr. Audas (image courtesy of OU Cousins).

Yoana Walschap mentors this organization (image courtesy of COLSA).

Building Institutions

From the 1980s on, several organizations focused on serving Latino communities throughout the state. Media companies found a large audience waiting for content delivered in Spanish. Support organizations carry on a long tradition of mutual aid in Latino communities. Business leaders created both formal and informal groups to educate business owners and to build peer networks. Cultural and educational organizations provide a grounding in Latino youth’s respective culture while providing the means to access higher education and perform well there. Social media platforms have provided the means for new communities to form.

In 1988, Argentina native Rosa Quiroga King began publishing El Nacional and it continues publication today. The next year, Nancy Galvan, originally from Mexico, relocated from Chicago to start a dedicated Spanish-language radio station with the call letters KZUE. Much later, in 2004, Telemundo began broadcasting. Other Spanish-language publications, radio and TV joined these pioneers, including El Latino American, Hola Oklahoma, Univision, and numerous radio stations. There is even a YouTube channel, Huellas Latinas, focusing on stories about Latino communities in Oklahoma.

Rosa Quiroga King established the first Spanish-language newspaper in Oklahoma in 1988; photo by Steve Gooch (2012.201.B0334.0068, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

Advertisement for El Latino American, which began in 1994 (image courtesy of El Latino American).

Bella Gutiérrez, with former US ambassador Edwin Corr, reporting a story for Huellas Latinas (image courtesy Bella Gutiérrez)

Oklahoma City’s Hispanic Cultural Center closed in the late 1980s. It became evident that an organization that focused on providing social services to the metro area’s Latino population was needed. In 1991, the Latino Community Development Agency (LCDA) began with Ecuadorian Pat Fennell as executive director. LCDA offers a wide range of services including high-quality pre-K, health services, assistance to families experiencing domestic violence, and youth programs. Now under the leadership of former educator and Puerto Rican Raúl Font, the organization is working to add more services and update their historic building.

A group of entrepreneurs organized the Greater Oklahoma City Hispanic Chamber of Commerce in 2000. This organization provides training and advice to Latino business owners. The Chamber offers Latino Leadership OKC to develop community leaders. They also bring attention to their member businesses. Certification classes and job fairs round out their activities. The Hispanic Chamber Women’s Business Center seeks to support women entrepreneurs as they open and build businesses.

Patricia Fennell, founder of LCDA (image courtesy of The Oklahoman).

Miriam Campos learned leadership as a teenager by participating in LCDA’s Latino Club and now she serves on the LCDA Board of Directors (image courtesy Marylin S. Photography).

Business training at the Hispanic Chamber Women’s Business Center (image courtesy of the Greater Oklahoma City Hispanic Chamber of Commerce).

In Norman, Latinas WIN (Women in Norman) is a community organization devoted to supporting Latino students and their families. Offering a wide range of support, from mentoring to translation to academic enrichment, Latinas WIN organized in 2010 by Dr. Millie Audas and is comprised of professional woman originally from the US, South America, and Central America. They work with classroom teachers and serve as a bridge between the school and Latino families. Their central program, MOSAICOS, is an afterschool program for students at Truman Elementary. The women of Latinas WIN work directly with Latino families through this program. They support families with access to adult education, the arts, and mentorship.

Latinas WIN (image courtesy of Yoana Walschap).

In Tulsa, the Hispanic American Foundation, founded in 1990, works to support Latino students in addition to preserving and promoting Latino cultures. They offer a wide range of scholarships, totaling $45,000 to Tulsa county students in 2020. For younger students, they support English Language Learning and ballet classes. They also underwrite cultural events throughout Tulsa, such as Festival Americas and Dia de Los Muertos, in their effort to promote Latino cultures.

In Edmond, the Hispanic America Students Association has been a fixture at UCO for 26 years. They develop programs and activities that advance their mission of “Educate, Advocate, Celebrate, and Community.” The Carnaval event is designed to educate others about the Latin American countries that celebrate it. “Salsa Under the Stars” teaches the Latin dances of salsa and bachata. They fundraise to support children with leukemia and create job and employment opportunities in Guatemala and Nicaragua. UCO’s HASA hosts panels discussing topics like DACA, machismo, and mental health in the Latino community. Throughout Oklahoma, most major colleges and universities offer Hispanic American Student Association/Latin American Student Association organizations. Major elements of the mission of these organizations are community service, celebrating culture, and education.

Members of UCO HASA, 2019–20 (image courtesy Gerardo Santillan).

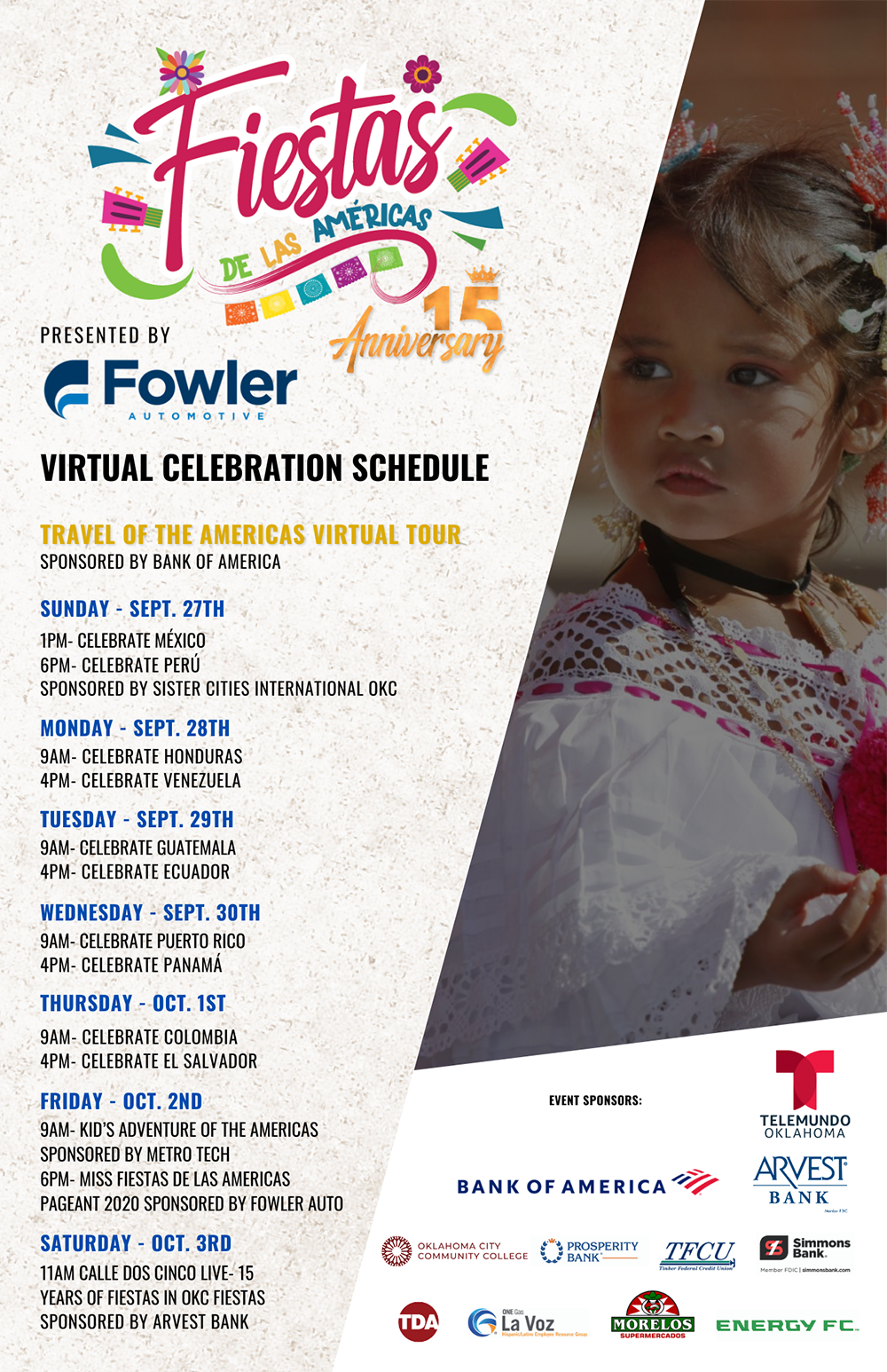

The past twenty years have seen an explosion of Latino-centered cultural and educational organizations. Calles Dos Cinco offers several programs devoted to the historic Capitol Hill neighborhood in Oklahoma City, but the largest and most well known is the annual Fiestas de las Americas celebration. This celebration brings Latinos from all over the region to celebrate their heritage and is a major annual attraction. The Hispanic American Foundation in Tulsa offers a wide variety of scholarships and cultural programs for Latinos in northeastern Oklahoma. The Oklahoma Latino Cultural Center and the Hispanic Arts Council are recent collective efforts to highlight the arts. Throughout Oklahoma, at colleges and universities, Hispanic American Student Associations provide college students connection to others with similar heritages and a way to serve their local communities in a coordinated way.

With the widespread adoption of social media, one use of these platforms has been the organization of groups to connect and celebrate individuals from specific national backgrounds. In Oklahoma alone, there is Asociación de Guatemala Unidos de Oklahoma, the Puerto Rican Foundation of Oklahoma, the Panamanian Society of Oklahoma, Salvadorans in Oklahoma, and the Colombian Society of Oklahoma. These groups organize cultural celebrations, support businesses of their members, and offer scholarships to students.

The Fiestas de las Américas is a large celebrations held yearly in Oklahoma City’s Capitol Hill neighborhood (Tierra de mi Familia: Oklahoma exhibit at the Oklahoma History Center, 2008, OHS).

Dancers preparing for the 2008 Fiestas de las Américas (Tierra de mi Familia: Oklahoma exhibit at the Oklahoma History Center, 2008, OHS).

In 2020, the 15th Anniversary Fiestas de las Américas Celebration was held virtually (image courtesy of Calle Dos Cinco).