Latino History in Oklahoma

1880s–1929

Population Pushes and Pulls

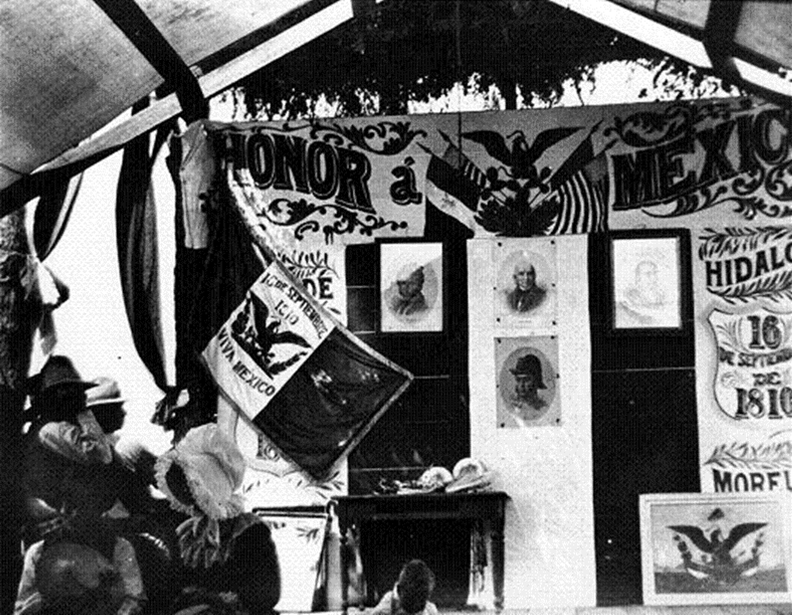

Mexican Independence Celebration in Anadarko, 1901 (image courtesy Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma).

Few Mexicans lived in Indian Territory before the 1900s. As Indian Territory opened up to settlement, it became an attractive destination for immigrants from around the world. Railroads came to Indian Territory in the 1870s. The Choctaw developed coal mines in southern Oklahoma and imported workers from many different places to work in the mines. This included a number of Mexicans. The expanding railroad industry also called for many workers willing to work long hours in dangerous conditions for relatively low pay. These two industries spurred a small Mexican migration to the state. The 1900 census records 134 Mexicans in Oklahoma and Indian territories, clustered in coal-mining communities in Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations. By the 1930 census, the population of Mexicans in Oklahoma reached 7,345.

The flow increased dramatically as changes in Mexico unfolded. The president of the country, Porfirio Díaz, changed the laws on land and agriculture. Many farmers lost the land they worked. Four railroads connecting the interior of Mexico to the border were completed by 1912. This allowed people to move more easily from their villages in Mexico to other places to find work. Many chose to try to find work in the United States. A lack of jobs kept many Mexican desperate for solutions. Farmworkers made the equivalent of 10–15¢ and a daily corn ration for a twelve-hour day. In other jobs, the wages in the United States were often 4–5 times higher than what a person could make doing the same job in Mexico. Then, in 1910, the Mexican Revolution began. In ten years, over ten percent of the population fled the country and most moved northward.

At this time, there were few or no restrictions on immigration from elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere while there were increasing limitations on immigrants from most other places. The Chinese Exclusion Act, passed in 1882, blocked the Chinese from immigrating to the US. The Chinese have served as a primary pool of labor for early Western industries such as railroads and mining. After passage of the act, they were no longer allowed entry. Other laws attempted to prevent people who might be poor or who were promised a job from immigrating to the United States. During parts of the first two decades of the twentieth century, these laws were seldom enforced for Mexicans. At other times, employers within the US pushed the government to officially waive the rules. During World War I, Mexicans were actively recruited, and the US government supported these efforts.

Work

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the southwestern United States offered easy employment to many as there were several booming industries seeking laborers. The work available was extremely physical and dangerous. There were more jobs than there were people willing to work in those jobs. Employers in this area regularly used a dual wage system, offering better pay to white workers. Because they could pay non-white workers less, employers were willing to hire people from all backgrounds. Mining, railroad work, and farm work employed many of the Mexicans and Tejanos moving to Oklahoma. Meat-packing plants, as they became established in the state in the 1910s, joined this list.

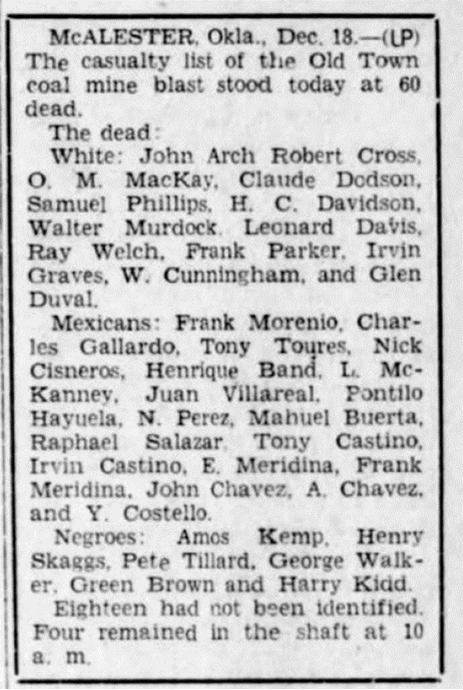

These jobs offered pay significantly higher than the wages offered elsewhere. Strong English-speaking skills were not required. Many of the jobs were seasonal, allowing individuals and families to travel to visit family without fearing the loss of a job. Mining and railroad work offered the opportunity to work with relatives or close friends. Railroad maintenance crews, often made up of non-English speakers, worked in teams that shared a language. In coal mines, miners worked in two-person teams, and the miner could select his partner. In 1929, this benefit contributed to a major tragedy. In McAlester, at the Old Town coal mine, an explosion occurred, killing 61 people. Half of those killed were Mexican workers, including five sets of brothers.

Casualty list published in the Sapulpa Herald on December 18, 1929 (1522731, OHS).

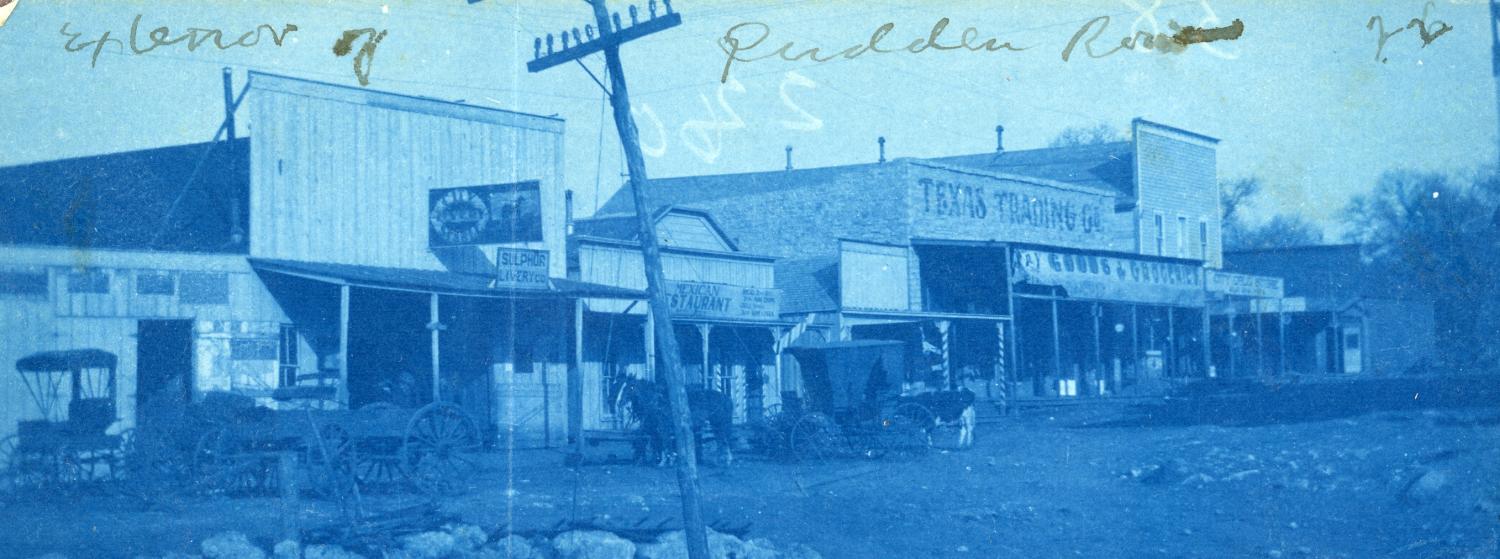

Mexican restaurant in Sulphur, 1900 (2153.16, Oklahoma Historical Society Photograph Collection, OHS).

Culture

Generally, many Mexican-born individuals living in Oklahoma planned on returning to Mexico at some point in the future. The revolution brought more women and children. Men worked outside of the home, and women expected to work within the home. Celebrations included the entire Spanish-speaking neighborhood. These celebrations included food, games, dancing, and music like mariachi and ranchera. The biggest celebrations in the Mexican community were Mexican Independence Day on September 16 and the celebration of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Religion played a very important role in the lives of Mexicans in Oklahoma, most of whom were members of the Roman Catholic church. In 1914, during the Revolution, four monks were forced to leave Mexico. They were assigned to establish a mission for a large number of Spanish-speaking Catholics in Oklahoma. The monks first set up a mission in the coal-mining areas of southeastern Oklahoma but relocated to Oklahoma City in 1921. These monks began fundraising for a church, which held its first service in 1927. This church is named Little Flower Catholic church and is a landmark in Oklahoma City today.

Nestor and Paz Cervantes in Dow, Oklahoma, 1910 (Tierra de mi Familia: Oklahoma exhibit at the Oklahoma History Center, 2008, OHS).

Little Flower men’s group in 1927 (image courtesy of The Oklahoman).

Wider Community

A large number of immigrants from all over the world called Oklahoma “home” during the Territorial and early Statehood periods. It was common for a town to be subdivided into neighborhoods of individuals who shared a culture, language, or nationality. Outside of the neighborhood, Mexican residents interacted with people from other backgrounds frequently when working, shopping, or traveling. Often, non-Mexican patrons frequented a favored restaurant owned by a Mexican person or family. Some people and groups in the wider community tried to make sure that families, including those from Mexico, had what they needed and offered support. Mexicans living in Oklahoma also faced regular discrimination and prejudice. Sometimes, other residents would use their greater power or violence to force Oklahomans from Mexico to move or quit their job.

Little Flower Catholic Church operated a school, a community center, and a health clinic for people living in the primarily Mexican neighborhoods surrounding it. The Goodwill Center in Oklahoma City, operated by the Baptist Missionary Society, focused much of their efforts on the Mexican residents of “Packingtown” a neighborhood near the stockyards. They offered a health clinic, ran a daycare for working mothers, and English classes. They organized holiday gift baskets every December.

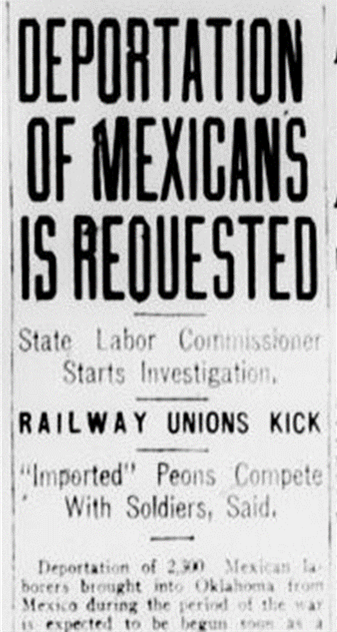

Hostility defined many interactions between Mexican residents and other Oklahomans. Little Flower Catholic Church toned down the design of their church because they feared being targeted by the Ku Klux Klan if they built the elaborate structure originally planned. Law enforcement officials frequently made claims about crime in Mexican neighborhoods that were false. In Oklahoma City, after police arrested several Mexican men, the judge ordered them to leave the city. During World War I and the early 1920s, newspapers and telegrams document several threats of lynching or forcing entire Mexican neighborhoods to leave the towns where they lived and worked. In 1914, people in Bartlesville reportedly succeeded in forcing the Mexican population of the town onto trains and made them leave. In 1919, a public debate emerged about how competitive Mexican workers were to white workers. Some people argued for the deportation of all Mexicans living in Oklahoma, and the state employment office studied this issue. Rumors of lynching sometimes reached the Mexican consul who compelled the governor of Oklahoma to investigate.

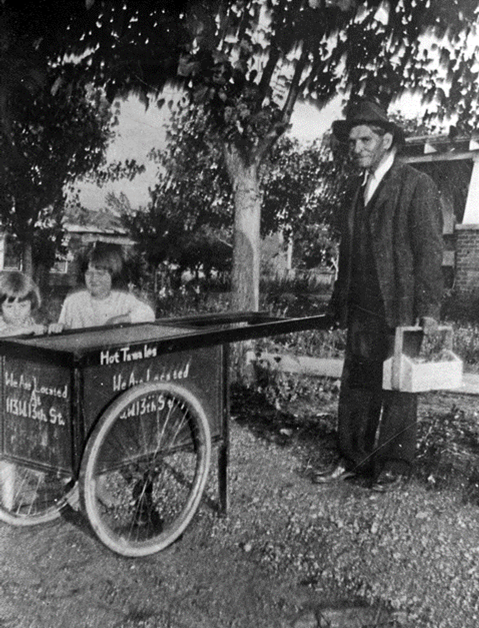

Francisco Zamudio fled the Mexican Revolution and settled in Ada, Oklahoma, where he began with a tamale cart. Eventually, he and his family would own several restaurants (image courtesy of the Western History Collection).

Oklahoma City Times, April 15, 1919.