Latino History in Oklahoma

1939–1979

World War II

World War II significantly impacted Latino families in the United States. Over 500,000 Latino Americans fought in World War II. This represents a significant portion of the Latino population. On the home front, work in the high-demand, high-paying defense industry was available only to US citizens. This spurred many Mexican residents to pursue naturalization. The Mexican and United States governments reached an agreement to allow a large number of Mexican workers entry into the United States to work in agriculture, railroad, and mining in the Bracero program. This program, embraced by large growers, continued well past the war and into the early 1960s. The war also produced an increased demand for the rights of Latino Americans.

One of the many Mexican-Americans awarded the Medal of Honor was originally from Oklahoma. Manuel Perez Jr., fought in the Pacific theater. He participated in the Battle of Luzon in the Philippines campaign and earned the Medal of Honor for his actions. Pinned down by the Japanese during the battle, Perez assaulted the fortified pillboxes that protected the enemy. He singlehandedly attacked the positions with grenades and killed 18 enemy soldiers. His division, no longer pinned down by enemy fire, was able to move forward toward the objective. A month later, Perez was killed by a sniper in the Philippines at the age of 22. He was buried in Oklahoma City. On February 22, 1946, US officials presented the Medal of Honor to Perez’s father on the International Bridge between the United States and Mexico.

PFC and Medal of Honor recipient Manuel Perez Jr. (image courtesy University of Texas at Austin).

Puerto Ricans

World War II also introduced diversity into Oklahoma’s Latino population. The war produced the first communities of Puerto Rican families in the state. Puerto Rico became a part of the United States as a result of the Spanish-American War. The United States established birthright citizenship for Puerto Ricans beginning in 1917, fostering large Puerto Rican communities in the continental United States and a high degree of participation in the military. Over 65,000 Puerto Ricans served in the military in World War II. This tradition of service, veteran status, and bilingual ability made them strong candidates to fill roles on the growing number of military bases after the war.

In 1950, United States and Puerto Rican leadership embarked on an ambitious program to improve the economy on the island called Operation Bootstrap. For a long period of time, this process created a lack of opportunity on the island and many Puerto Ricans decided to move to the continental United States for better employment. Many Puerto Ricans found that opportunity in or around the military bases in Lawton, Midwest City, and Enid.

Rachel Rodriguez, from Puerto Rico, an Oklahoma City resident in the 1950s (2012.201.B1134.0161, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

Cubans

After a successful revolution placed Fidel Castro in control of Cuba in 1959, some Cubans expressed disagreement with the country’s direction under his leadership. Of those Cubans that opposed the government, some decided to leave the country, often choosing the United States. The US, also in opposition to the Castro government, welcomed these Cubans, and even passed a law that made it easier for Cubans to immigrate than for people from other places.

There were periods when large numbers of people migrated out of the country. In the early 1960s, many, especially people who held property and professional positions, left the country. This period also included a migration of unaccompanied children in Operation Peter Pan. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Cubans leaving the country participated in the “Freedom Flights,” ten flights a week from Cuba to Miami, agreed upon by the US and Cuban governments. In 1980, another peak of migration occurred during the Mariel Boatlift when the Cuban government briefly lifted its restrictions on emigration, which had been closed. A large number of Cuban exiles arranged 1,700 boats to pick up people wishing to leave at the Mariel port.

While most Cubans stayed on the East coast, some did settle in Oklahoma. Some churches and church groups in the state pooled their resources to sponsor Cuban resettlement. Later, during the Mariel Boatlift, a nearby refugee detention center in Fort Chafee, Arkansas, increased the number of Cuban migrants in the region. By 1965, approximately 300 Cubans made Oklahoma their home, largely in Oklahoma City and Tulsa. Oklahoma City mayor James Norick and his wife, Madalynne, hosted a young Cuban woman named Leyda Hernandez after the Bay of Pigs incident in 1961.

Madalynne Norick and Leyda Hernandez in 1962 (2012.201.B0288.0027, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

The Leon family arriving in Oklahoma City in 1971 (2012.201.B0370.0419, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

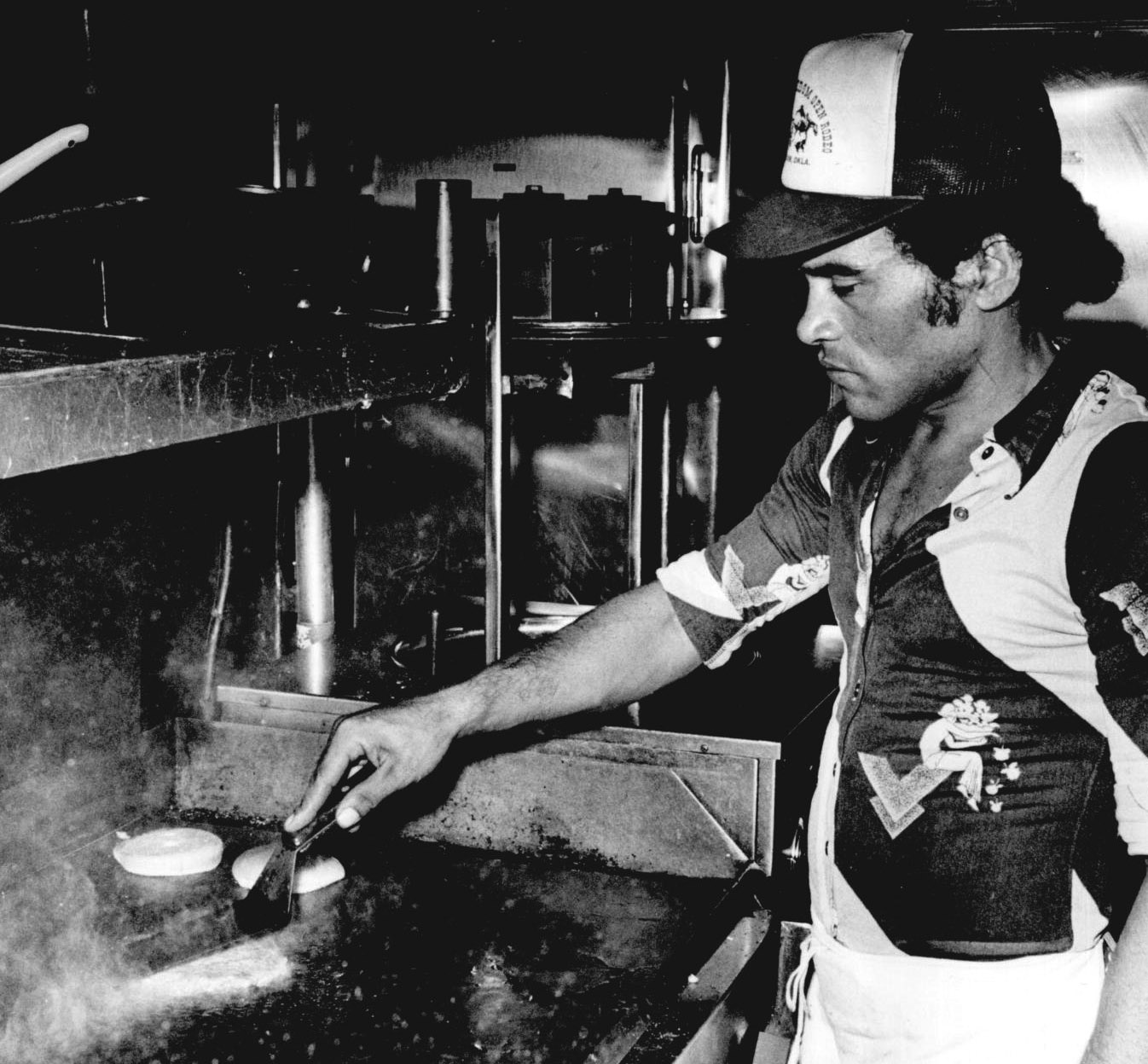

Formerly a chef in Cuba, German Hernandez, a Marielito, found work in a Pond Creek, Oklahoma, diner in 1980 (2012.201.B0257.0271, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

1965 Immigration Act

In 1965, the Hart-Cellar Act became law and fundamentally changed the United State’s immigration system. Previously, the immigration system was based on quotas established for different countries. Those quotas contained a much higher number for individuals moving from northern and western Europe than anywhere else. However, quotas were not applied to the countries in the Western Hemisphere. With this new law, a 120,000-per-year cap was placed on immigrants from the Western Hemisphere. The criteria for granting legal permanent residency (green card) in the US were based on job skills and family already living in the United States. These caps did not align with the concrete number of migrants moving to the United States. This, along with the end of the Bracero program in 1964, resulted in more undocumented entries into the country.

Guatemalans

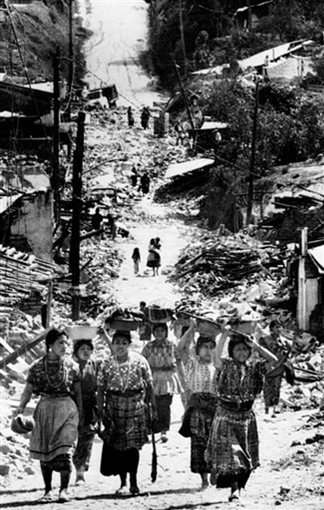

The 1976 earthquake worsened conditions in war-torn Guatemala (image courtesy AP News).

Guatemala has been closely connected with the United States since the early twentieth century. An American company, United Fruit, gained significant power in Guatemala’s government. The US government offered extensive support to keep this arrangement, even when the people of Guatemala attempted to change the government in the 1950s. From this conflict, a civil war waged in the country for thirty years. Then, in 1976, an earthquake devastated the country, killing over 23,000 people and leaving a sixth of the population homeless.

The beginning of the Guatemalan community in Oklahoma partly centers on the efforts of Sister Joselita Allen. Sister Allen, originally from Mexico, served in several Catholic churches in Oklahoma. Then she worked in Guatemala for nine years before returning to Oklahoma. While in Guatemala, she organized a youth marimba band and brought them to the United States for a tour, stopping in Oklahoma first. Later, she arranged for Benvenuto Barrios to come to Oklahoma City so he could go to school at Bishop McGuiness. He recalls meeting only one other person of Guatemalan heritage when he moved here, a hospital worker at St. Anthony’s, who later moved away. Benvenuto Barrios moved here permanently, and his brother joined him soon after. Other Guatemalan families followed, especially after the earthquake.

Sister Joselita Allen with Sister Martin preparing for Guatemala in 1962; photo by Austin Traverse. (2012.201.B0319B.0306, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS)

Building Institutions

The Latino communities in Oklahoma established a wide range of businesses, events, and organizations. The Little Flower Festival, which began in 1934, became an institution during this period. After World War II, both Oklahoma City and Waynoka hosted large celebrations of Mexican Independence Day that drew participants in the hundreds. Beginning in 1947, the Catholic Action Club with Little Flower Catholic Church began hosting the annual independence celebration in Oklahoma City. In 1960, a chapter of the American G.I. Forum organized in Oklahoma City. This organization was founded by Texan, Dr. Hector Garcia, to advocate for the rights of Latino Americans. Jesse Martinez was a driving force behind this organization in Oklahoma. The Oklahoma City chapter hosted dances at the Myriad and used the proceeds to fund scholarships. In 1971, the ORO Development Corporation began with the mission to offer opportunities to migrant and seasonal farmworkers. The workers the organization initially supported were primarily Spanish-speakers; they now provide services to a wide variety of rural residents in Oklahoma.

American GI Forum scholarship recipients in 1979. Photo by Paul B. Southerland (2012.201.B1102.0329, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

Preparing tamales for the Little Flower Festival in 1977(2012.201.B0119A.0462, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

Rosemary Negrete, 1956 Waynoka Fiesta Queen, September 14, 1956 (473163, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

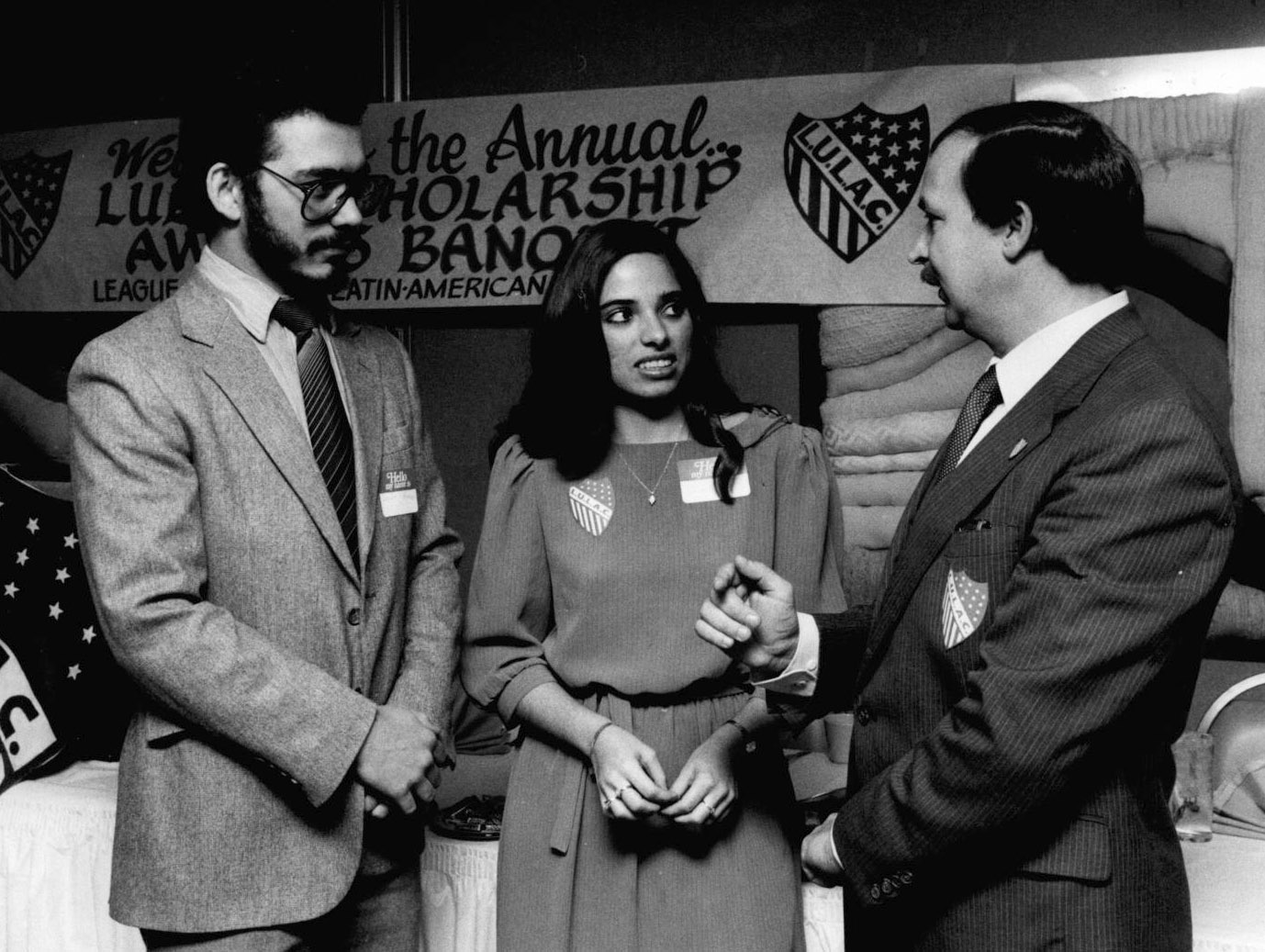

Dr. Edward Esperanza established the Mexican-American Cultural Center in 1974; it was later renamed Hispanic Cultural Center in 1980 to reflect the varied community of Spanish-speakers who attended its English-language, immigration, job skills, and dance classes. Anita Martinez opened La Puerta de Oro, a senior citizens’ center for Spanish-speakers. From this base, she also organized Los Viejitos, a popular mariachi band. In 1979, Alfonso Macias organized chapters of LULAC (League of United Latin American Citizens) in the state. LULAC Oklahoma offers voter education, youth leadership, and scholarship opportunities.

Police presentation at Mexican-American Cultural Center in 1976; photo by Michal Thompson (2012.201.B0397.0228, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

Alfonso Macias, right, with LULAC scholarship winners in 1983; photo by George Wilson (2012.201.B0380.0211, Oklahoma Publishing Photography Company Collection, OHS).

Seniors enjoying lunch at La Puerta de Oro in 2018 (image courtesy of Telemundo).