The Opening of Oklahoma

The Jerome Commission

Several commissions were organized after the Dawes Act. They were tasked with negotiating with different tribes. Their goal was to get the tribes to accept allotment and to sell the surplus land to the US government. The Jerome, or Cherokee, Commission was assigned several tribes and were to negotiate with the Cherokee to surrender a part of their territory called the Cherokee Outlet. Except for the Cherokee, they focused on the tribes in western portion of Indian Territory. These included the Iowa, Sac and Fox, Potawatomi, Shawnee, Cheyenne and Arapaho, Wichita, Kickapoo, Tonkawa, Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache. Because most of the other commissions dealt with one or two tribes, the Jerome Commission set the primary approach to the process of allotment.

Their negotiating strategy left little opportunity for compromise. The commissioners explained that allotment would happen either under agreements they negotiated or it would happen under the authority of the Dawes Act. If allotment was done under the Dawes Act, those receiving land would receive smaller parcels of land and no additional money from the sale of surplus lands. The commission argued that those receiving land would be more wealthy than any white man because each family member would receive an allotment and that tribal members should appreciate the opportunity to have land and live like non-Indians. Some or all of the land would not be able to be taxed or sold until a period of time passed, usually twenty-five years. If the owner rented or leased the land in the meantime, the money would be paid to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the owner would get a small monthly allowance, usually ten dollars. The commission was authorized to pay up to $1.25 per acre for the surplus land, but they never came close to paying that price to any of the tribes. The agreements the commission signed paid a range of 27¢ to $1 per acre, depending on the agreement.

In the twentieth century, most of these payments were found to be far too low and the tribes received additional payment. Another issue that government officials later acknowledged was that the commission did not follow rules of some earlier treaties that required a percentage of the entire tribe consent to a new treaty or the sale of tribal land, even though the commission knew about this requirement.

In addition to negotiating with the western tribes, the Jerome Commission was tasked with securing the Cherokee Outlet from the Cherokee tribe. This proved challenging as the tribe had turned that territory into a money-maker by leasing the land to cattle ranchers. The tribe did not want to lose the land that allowed them to earn hundreds of thousands of dollars. Negotiations dragged for months until President Benjamin Harrison outlawed grazing in the outlet and sent in the army to remove the ranchers. This eliminated the source of revenue the Cherokees had been trying to protect, and they agreed to terms.

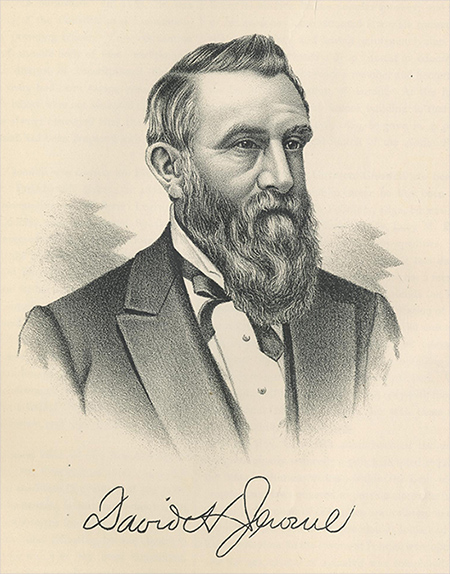

Commissioner David Jerome (image courtesy Bentley Historical Library).

Reception and Resistance

When the Jerome Commission began their negotiations, most of the tribes believed that the US government recognized their sovereignty and that they would have a voice in what happened. So, the tribes the Jerome Commission negotiated with in 1890 and 1891 told the commission members that they preferred to keep the reservation as is. They expressed strong opposition to the concept of allotment. Breaking the land up and living as farmers held no charm for the Iowa, Sac and Fox, Kickapoo, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. These communities lived in closely laid out villages, which allotment would disrupt. Farming was not a primary economic activity for these tribes. For these groups, the farming the tribes did was women's work, so the commission was asking these communities to adjust their understanding of gender roles. Basically, they objected to the entire proposition.

Once it became clear that allotment would proceed with or without the tribes' consent, the tribal nations took different approaches. The Sac and Fox negotiated quickly and received larger acreages than most of the other tribes. Several tribes attempted to hire lawyers. The members of the Jerome Commission pushed back hard against this, even though the lawyers who found a place at the negotiating table worked to convince the tribes to cooperate with the government.

The most frequent resistance offered, by both governments and individuals within tribes, was noncooperation. Consistently, tribal leaders refused to agree to terms, and individuals opposing allotment refused to participate in the selection of land. The Osage, Kaw, Otoe, and Ponca never reached agreements with the Jerome Commission, although they did undergo allotment under the Dawes Act.

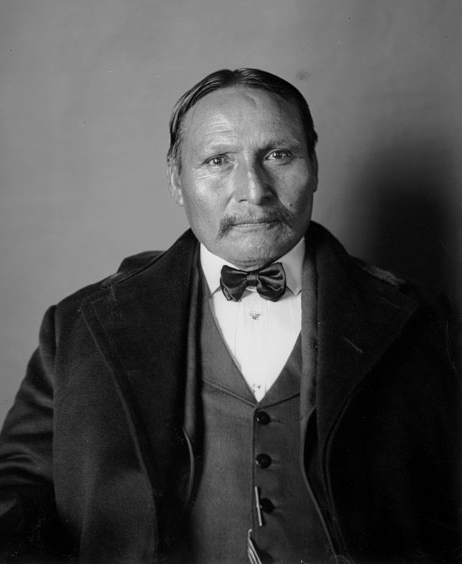

In addition to noncooperation, the Kiowa leader Lone Wolf took the government to court and the case reached the Supreme Court in Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock (187 U.S. 553, 1903). He wanted the courts to stop allotment. The court found that Congress could constitutionally break treaties with tribe because they had absolute, or plenary, power over Indian policy.

Lone Wolf the Younger (image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution).